|

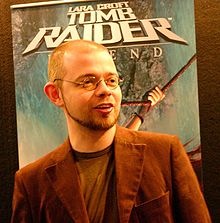

Toby Gard

Toby Gard (born 8 June 1972) is an English video game character designer and consultant. He was part of the team that created fictional female British archaeologist Lara Croft.[2] Lara Croft was awarded a Guinness World Record recognizing her as the "most successful human video game heroine".[3] Biography1990s: From Tomb Raider to Confounding FactorToby Gard was born on 8 June 1972 in Chelmsford, Essex, England. He began his career in videogames in 1994 when he was hired by Core Design to work on the game BC Racers. From 1995 he was part of the team who designed and developed the original Tomb Raider video game along with the character Lara Croft. His work on the game included building and animating most of the game's characters (including Lara), animating the in-game cutscenes, storyboarding the FMVs, and managing the level designers.[4] Core gave Gard creative control over the game, although it was clear they wanted to market Lara's sex appeal, even asking Gard to implement a nude code into the game, which he refused to do.[5] His vision for Lara was "a female character who was a heroine, you know, cool, collected, in control, that sort of thing" and that "it was never the intention to create some kind of 'Page 3' girl to star in Tomb Raider".[6] Gard left Core Design in 1997. With Tomb Raider already an established hit, Core was no longer giving Gard the creative freedom he originally had. In the end, he was given the choice of making a Tomb Raider port for the Nintendo 64, or working on Core's vision for Tomb Raider II. Neither option appealed to him, so he left the company.[5] Gard had been headhunted by other software companies including Interplay and Shiny Entertainment (which prematurely announced that it had hired Gard[7]) but did not take up their offers of employment.[8] In 1997, he formed the company Confounding Factor along with co-developer Paul Douglas, who had worked with Gard on Tomb Raider. Galleon was announced soon after. The game had a protracted development period and was released in 2004 on Microsoft's Xbox.[8] 2000s: Return on Tomb RaiderAfter the closure of Confounding Factor, Gard was re-hired by Eidos (then publisher and copyright holder of the Tomb Raider series) to work with Crystal Dynamics on a reboot of the Tomb Raider franchise, beginning with Tomb Raider: Legend. While initially hired as a creative consultant, his work became "hands on" during the production and eventually included Lara's visual redesign, overseeing character design and creation, co-writing the story, designing and implementing parts of the character movement system, and directing the cinematics.[4] The next game in the series, Tomb Raider: Anniversary, was a re-imagining of the original Tomb Raider. It was co-developed by Crystal Dynamics and Buzz Monkey Software. Gard's role on Anniversary was limited to "story consultant", while also adding his voice to the audio commentary included in the game.[9] For Tomb Raider: Underworld, Gard's work included co-writing the story, directing the cinematics, voice direction, motion capture direction (along with camera setup and managing the animators and lighters), and directing the European TV advert for the game.[4] Gard and Eric Lindstrom received a nomination for "Best Writing in a Video Game" by the Writers Guild of America for their work on Underworld.[10] 2010s: Otherworld, Ninja Gaiden Z, and a new studioFrom 2010 to 2012, he worked on a webcomic called Otherworld.[11] From 2012 to 2014 Gard was the game director for Yaiba: Ninja Gaiden Z at Spark Unlimited.[4] In 2014 Gard founded a new studio called Tangentlemen,[12] where he would work as director on Playstation VR title Here They Lie.[13] He has been the owner of Cathuria Games since 2019, where he worked on indie game Dream Cycle.[4] InspirationGard listed Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss, EverQuest, Super Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Full Throttle, Star Wars: X-Wing, Power Stone, Stunt Island, Spindizzy, and Super Bomberman as his favorite games in 2000.[14] References

Works cited

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Toby Gard. |

||||||||||||||