|

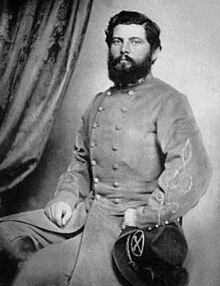

Thomas L. Rosser

Thomas Lafayette "Tex" Rosser (October 15, 1836 – March 29, 1910) was a Confederate major general during the American Civil War, and later a railroad construction engineer and in 1898 a brigadier general of volunteers in the United States Army during the Spanish–American War. Early life and careerRosser was born on a farm called "Catalpa Hill", in Campbell County, Virginia, the son of John and Martha Melvina (Johnson) Rosser. In 1849, the family relocated to a 640-acre (2.6 km2) farm in Panola County, Texas, some forty miles west of Shreveport, Louisiana. The 13-year-old Tom Rosser led the wagon train bearing his mother and younger siblings westward, as business considerations compelled his father to remain in Virginia for a short time. Texas Congressman Lemuel D. Evans appointed Rosser to the United States Military Academy in 1856. However, Rosser did not complete the required five-year course of study, as Rosser, a supporter of Texas secession, resigned when Texas left the Union on April 22, 1861, two weeks before the scheduled graduation. Rosser traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to enlist in the Confederate States Army. Thomas Rosser's roommate at the academy, George Armstrong Custer was a close friend and despite being on opposing sides this friendship continued both during and after the Civil War ended. He was known for his "hit and run" raids. Civil War Rosser was commissioned a first lieutenant and became an instructor to the famed "Washington Artillery" of New Orleans. He commanded its Second Company at the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861. He was noted for shooting down one of George B. McClellan's observation balloons, a feat that won him promotion to captain. He commanded his battery during the Seven Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign, and was severely wounded at Mechanicsville. Rosser was promoted to lieutenant colonel of artillery, and a few days later to colonel of the 5th Virginia Cavalry. He commanded the advance of J.E.B. Stuart's expedition to Catlett's Station, and was notable in the Second Battle of Manassas, where captured Union commander John Pope's orderly and horses. During the fighting at Crampton's Gap at the Battle of South Mountain, his cavalry delayed the advance of William B. Franklin's VI Corps with help from John Pelham's artillery. At Antietam, his men screened Robert E. Lee's left flank. He temporarily assumed command of Fitzhugh Lee's brigade during the subsequent fighting against Alfred Pleasonton. He was again badly wounded at the Battle of Kelly's Ford, where "the gallant" Pelham was killed. Rosser was disabled until the Gettysburg Campaign, where he commanded his regiment in the fighting at Hanover and the East Cavalry Field at Gettysburg. He was promoted to brigadier general of the "Laurel Brigade," which had gained fame under Turner Ashby. He was distinguished again in the 1864 Overland Campaign, driving back a large force of Union cavalry and artillery at the Battle of the Wilderness. Rosser was yet again wounded at Trevilian Station, where his brigade captured a number of prisoners from former West Point classmate and close personal friend George Armstrong Custer. His brigade later gallantly fought against Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley, and he efficiently commanded Fitzhugh Lee's division at Cedar Creek. A rare defeat where Custer overran Rosser's troops at the Battle of Tom's Brook allowed Custer to repay Rosser for Trevilian Station. For no tactical reason, Custer chased Rosser's troops for over 10 miles and the action became known as the "Woodstock Races" in Union accounts. Custer had also captured Rosser's private wardrobe wagon at Tom's Brook, and Rosser immediately messaged him.

Custer shipped Rosser's gold-laced Confederate grey coat to his wife with a reply.

Rosser became known in the Southern press as the "Saviour of the Valley," and was promoted to major general in November 1864. He conducted a successful raid on New Creek, West Virginia, taking hundreds of prisoners and seizing much need quantities of supplies. In January 1865, he took 300 men, crossed the mountains in deep snow and bitter cold, and surprised and captured two infantry regiments in their works at Beverly, West Virginia, taking 580 prisoners. Most of the men in Rosser's command were recruits from West Virginia.[1] Rosser commanded a cavalry division during the Siege of Petersburg in the spring, fighting near Five Forks. It was here that Rosser hosted the "infamous" shad bake (fish feast) 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the battle lines preceding and during the primary Federal assault. Guests at this small affair included George Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee. Shelby Foote states that "Pickett only made it back to his division after over half his troops had been shot or captured..". It is said that Lee never forgave Pickett for his absence from his post when the Federals broke the Confederate lines and carried the day at Five Forks. Rosser was conspicuous during the Appomattox Campaign, capturing a Union general, John Irvin Gregg, and rescuing a wagon train near Farmville. He led a daring early morning charge at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, and escaped with his command as Lee surrendered the bulk of the Army of Northern Virginia. Under orders from the secretary of war, he began reorganizing the scattered remnants of Lee's army in a vain attempt to join Joseph E. Johnston's army in North Carolina. However, he surrendered at Staunton, Virginia, on May 4 and was paroled shortly afterwards. Postbellum activitiesRosser was superintendent of the National Express Company, working for fellow ex-Confederate general Joe Johnston. He resigned to become assistant engineer during the construction of the Pittsburgh & Connellsville Railroad. He became chief engineer of the eastern division of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Later he was chief engineer of the Canadian Pacific. He worked for the C.P.R. for less than a year before being fired for corruption. Using his position in the C.P.R., Rosser had amassed on the side a fortune of more than $130,000 through speculation and other questionable means.[2] Rosser was believed to have altered the preliminary survey of the line in Saskatchewan to bring it through Regina where he had money invested.[3] Rosser engaged in efforts to honor the Confederacy after the war. He worked to have Confederate monuments constructed despite having been explicitly discouraged from doing so in a now famous 1866 personal letter from Robert E. Lee.[4] When Custer was defeated at the Battle of Little Bighorn, Rosser wrote an article in the Chicago Tribune placing the blame on Custer's subordinates. Rosser later retracted his claims when Major Reno threatened a lawsuit.[5] In 1886, he bought a plantation near Charlottesville, Virginia, and became a gentleman farmer. On June 10, 1898, President William McKinley appointed Rosser a brigadier general of United States volunteers during the Spanish–American War. His first task was training young cavalry recruits in a camp near the old Civil War battlefield of Chickamauga in northern Georgia. He was honorably discharged on October 31, 1898, and returned home. He died at Charlottesville and is buried at Riverview Cemetery, Charlottesville. Biographers describe Rosser as a man driven by a desire for financial gain, and a person who could be “arrogant, aggressive, racist, and proud to a fault.”[6] Rosser Avenue in Brandon, Manitoba is named in his honor, as well as the village and Rural Municipality of Rosser near Winnipeg.[7] There is also a Rosser Avenue in Bismarck, North Dakota. This was platted before Custer's arrival in the area, and so likely is related to Rosser's time with the railroad (Northern Pacific) rather than his friendship with Custer, or his military career. There is also a Rosser Avenue in Waynesboro, Virginia. In Charlottesville, Virginia there are both Rosser Avenue and Rosser Lane. See alsoReferences

Notes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas L. Rosser. |

||||||||||||||||||||||