|

The Modern Cook

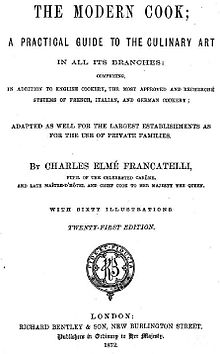

The Modern Cook was the first cookery book by the Anglo-Italian cook Charles Elmé Francatelli (1805–1876). It was first published in 1846. It was popular for half a century in the Victorian era, running through 29 London editions by 1896. It was also published in America. The book offered elaborate dishes, described with French terminology such as bisque, entrées, entremets, vol-au-vent, timbale and soufflé. It included bills of fare for meals for up to 300 people, and for a series of eight- or nine-course dinners served to Queen Victoria; one exceptional royal dinner in 1841 had sixteen entrées and sixteen entremets, including truffles in Champagne. The book, written for upper middle-class housewives, is illustrated with 60 engravings, often showing how to present carefully decorated centrepiece dishes such as "Salmon à la Chambord" for large dinner parties. The book influenced households in Britain and America to aspire to more complex, French-style dinners in imitation of the Queen, and resulted in a change in eating habits, including the modern two-course approach for both lunch and dinner. ContextCharles Elmé Francatelli, from an Italian family, was born in London in 1805, and learnt cookery in France. Coming to England, he worked for various aristocrats before becoming chief chef of Crockford's club and then chief cook to Queen Victoria in 1840.[1] He went on to work at Crockford's again, at the Coventry House and Reform Clubs, St James's Hotel, and for the Prince and Princess of Wales.[2] This made him a celebrity cook of his time.[3] BookApproach Apart from the preface and Francatelli's advice on serving wine, the body of the book consists almost entirely of recipes without any kind of introduction. There is no guidance on choice of kitchenware or advice on the layout of the kitchen.[4] The recipes are presented entirely as instructions, generally without illustration.[a] Quantities, where stated, are incorporated in the text; ingredients are never listed explicitly. Quantities are sometimes named, as in the "Cream Bechamel Sauce", which begins "Put six ounces of fresh butter into a middle-sized stewpan; add four ounces of sifted flour, some nutmeg, a few peppercorns, and a little salt;". In other cases only the relative proportions are indicated, as for the "Salmis of Partridges with Aspic Jelly", where the only hint of quantity in the recipe is "must be mixed with one-third of its quantity of aspic jelly". This recipe also indicates the style of cross-referencing, with the starting instruction "Prepare the salmis as directed in No. 1078".[4]  The Modern Cook is the first published record in England of filling wafer cornets, which Francatelli called gauffres, with ice cream. He used them to garnish his iced puddings.[5] ContentsThe following apply to the 28th edition of 1886. The table of contents did not have page numbers.[4]

Illustrations The 28th edition is illustrated with 60, mostly small, engravings. There is a full-page frontispiece of the author, drawn by Auguste Hervieu and engraved by Samuel Freeman (1773–1857).[6] Freeman is known for working mainly in stipple, and the portrait here is no exception.[7] All the other engravings are of completed dishes, showing the serving-plate with the food arranged on it and often elaborately garnished. The artists and engravers of the food illustrations are not identified.[4] Bills of fare Francatelli provides "A Series of Bills of Fare for Every Month Throughout the Year", including dinners variously for 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 16, 18, 20, 24, 28 and 36 persons (though not all of these in every month). The bills of fare for dinners for 6 persons thus represent the simplest menus in the book. All the dinners are divided into a first and a second "Course", but each course was divided in turn into three or four servings, in most cases with a choice of two or more dishes. Thus there might be one or two soups, two fishes, two "removes" of meat, and two savoury "entrées" in the first "Course", with a second "Course" of one kind of game, followed by a choice of three "entremets" which included both savouries, generally vegetables, and desserts.[4] There is a single bill of fare for a "Ball Supper for 300 Persons", and one for a "Public Dinner" for the same number.[4]  There are 13 bills of fare for "Her Majesty's Dinner", each with an exact date in 1841 and the words "(Under the control of C. Francatelli.)". Each of the royal dinners has either eight or nine courses (including a buffet or sideboard), except for that of 30 June which is divided into two "Services" and has 11 courses.[4] The royal dinners are described almost entirely in French, with the exception of the heading, the phrase "Side Board", and a few specifically British dishes such as "Roast Mutton" and "Haunch of Venison". There are usually two soups, two fishes, two removes, six entrées, two roasts, two more removes, six entremets, and between two and seven dishes on the sideboard. The exceptional royal dinner of 30 June 1841 had sixteen entrées and sixteen entremets. Some of these entremets used the most costly ingredients, including truffles in Champagne.[4] PublicationThe Modern Cook was first published in 1846.[8] It reached its 29th edition in 1896. Francatelli presented a copy of the 8th edition to Queen Victoria on 4 June 1853.[9] Editions included:

ReceptionContemporary Kettner's Book of the Table of 1877, describing Francatelli as "a type of all the great French cooks", asserted that he "gives a most elaborate recipe for aspic jelly; and he is so satisfied with it that, having to prepare a cold supper for 300 people, he works it up in every one of his 56 dishes which are neither sweet nor hot. The book further argues that "this is the result of science—this the height of art. It produces, with such elaborate forms and majestic ceremonies, an aspic jelly without aspic, that, exhausted in the effort, it can proceed no further, and seems to think that here at last, in this supreme sauce, we have a sure resting-place—the true blessedness—the ewigkeit."[10] George H. Ellwanger wrote in his Pleasures of the Table in 1902 that Francatelli's Modern Cook was "still a superior treatise, and although little adapted to the average household, it will well repay careful study on the part of the expert amateur. 'The palate is as capable and nearly as worthy of education as the eye and the ear,' says Francatelli — a statement which his volume abundantly bears out." He added that "one sees, accordingly, an ornate observance of decoration in his grand army of side-dishes. These are excellent throughout, but generally very elaborate, while his sauces and recipes for pastry are especially good. The same may be said of his quenelles and timbales. A competent hand will find his work a valuable guide from which to obtain ideas; it is not a practical book for the majority."[11] The New Zealand Herald of 1912 commented that Francatelli was "an earnest and gifted worker in the cause of gastronomy" and that The Modern Cook faithfully reflected Victorian dining habits. "Everything was good and solid of its kind, even if tending towards complication rather than simplicity." The review opined that the great joints of meat "decorated with their silver hatelet skewers bearing cock's combs and trufflets, were attended by the most appetizing ragouts and garnishes." Despite the gloss, there was "nothing meretricious or deceptive in the savoury promises held out by Victorian comestibles." The reviewer notes, however, that even while Francatelli was describing this elaborate fare, the "excessive meat-eating" was being replaced by a diet richer in vegetables, and meals were becoming simpler, so that "now, in the 20th century, much that Francatelli wrote about ... is no longer needed."[12] ModernM. F. K. Fisher, writing in The New York Times, stated that millions of American women in the 19th century organised "every aspect of their lives .. as much as possible in imitation of the Queen", and that The Modern Cook sold almost as well in America as it did in England. Admitting that few American kitchens could "follow all its directions for the light Gallic dainties Francatelli introduced to counteract the basic heaviness of royal dining habits", she argued that all the same his two-course approach eventually shaped the way Americans now eat both lunch and dinner. She observed that at Windsor Castle, Francatelli and other royal chefs were assisted by 24 assistant chefs and two "Yeomen of the Kitchen", not to mention a multitude of "servers and lackeys". This did not deter American housewives "as far west as Iowa and then beyond" from doing their best to follow his instructions.[13] The Historic Food website notes that Francatelli provides two recipes for mincemeat, one with roast beef, the other containing lemons but no meat.[14] C. Anne Wilson, introducing Women and Victorian Values, 1837–1910. Advice Books, Manuals and Journals for Women, states that Francatelli was writing for the "upper middle-class housewife" in The Modern Cook, explaining to her how to serve the "socially important" dinner in English, French and "à la Russe" styles. In contrast, his 1861 Cook's Guide is for "more ordinary" households, advocating "traditional two-course dinners".[15] Nick Baines writes on LoveFood that Francatelli included "a whole collection of lavish pies" in the book.[16] Panikos Panayi, in his book Spicing Up Britain, writes that Francatelli's book for the middle classes definitely recognised differences between British and foreign foods, even in its full title which ran "...Comprising, in Addition to English Cookery, the Most Advanced and Recherché Systems of French, Italian and German Cookery". Panayi notes that Francatelli's preface to the first edition was scathing about ignorant "English writers on gastronomy", comparing them unfavourably to the "great Professors" of cuisine in France. Panayi observes further that while most of Francatelli's chapters are not grouped by national origin, he does distinguish English, Foreign, and Italian soups. He notes that it would have taken years to eat all the dishes listed, and that it is impossible to tell how often middle-class families may have eaten "fillets of haddocks, à la royale". He considers it likely that only the wealthiest could have aspired to eat the sort of food described by Francatelli, but concedes that his bills of fare for dinners for six persons (by month) do indicate that the middle classes could afford the best meat and vegetables, and indeed that they had domestic staff able to prepare dinners of that complexity described in Francatelli's French terminology. Panayi concludes that Francatelli represents "perhaps the most extreme example" of the nineteenth-century British habit of giving dishes French descriptions.[17] NotesReferences

|

||||||||||||||||