|

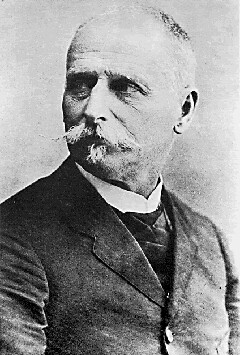

Teoberto Maler Teobert Maler, later Teoberto (12 January 1842 – 22 November 1917), was an explorer who devoted his energies to documenting the ruins of the Maya civilization. BiographyTeobert Maler was born on January 12, 1842, in Rome, Italy, to Friedrich Maler, a diplomat representing the Grand Duchy of Baden, and Wilhelmine Schwarz. His mother passed away in 1844 during the family's return to Baden, leaving Maler and his sister to be raised by their father. The early loss of his mother profoundly shaped Maler’s character, fostering a sense of independence and emotional resilience. His relationship with his father was distant and strained, a dynamic Maler later described in his autobiography Leben meiner Jugend (My Younger Years).[1][2] Maler studied engineering and architecture at the Polytechnic University in Karlsruhe (now Karlsruhe Institute of Technology), where he gained technical expertise that later influenced his detailed documentation of Maya ruins. In 1863, he moved to Vienna to work under Heinrich von Ferstel at the age of 21, a prominent architect known for designing the neo-Gothic Votive Church on Vienna's Ringstraße and became an Austrian citizen. Ferstel’s mentorship instilled in Maler a strong appreciation for precision and artistic composition, skills that became integral to his archaeological work. In 1864, Maler joined the military expedition of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico as a cadet and rose to the rank of captain. His initial interest in Mexico was centered on its colonial architecture, but following the fall of Maximilian's regime in 1867, Maler decided to remain in the country rather than being exiled back to Europe. This marked the beginning of his lifelong fascination with Mesoamerican culture and history, ultimately leading to his pioneering work documenting Maya ruins. Maler later obtained Mexican citizenship and changed his first name to "Teoberto", more easily pronounced in the Spanish language.  Maler developed interests in photography and in the antiquities of Mesoamerica. In 1876 he made detailed photos of the structures at Mitla. In the summer of the following year he moved to San Cristóbal de las Casas, and in July set out to visit the ruins of Palenque. While several accounts of the site had been published by this time, it was still little visited, and Maler needed to employ a team of the local Indios to open a path to the ruin with machetes. He spent a week at Palenque, sketching, measuring, and photographing the site, and became aware that earlier published accounts were inadequate, and that most earlier visitors had limited their descriptions to only a portion of the buildings observed there. While Maler was there another visitor came to the ruins, Gustave Bernoulli, a Swiss botanist who shared his interest in Maya sites, and had recently made a visit to Tikal. Bernoulli confirmed Maler's suspicion that there was much work that needed to be done to document the area's ruins. In the spring of 1878, Maler was obliged to return to Europe to settle his father's estate, which was tied up in considerable legal difficulties. While the lawyers he hired sorted it out, Maler lived in Paris, where he gave lectures on Mexican antiquities and studied and read everything about Mesoamerica he could find in the city. In 1884 the estate was settled, with Maler inheriting a small fortune, and he returned to Mexico to devote himself to study of the Maya. He settled in Yucatán with small house in the town of Ticul, where he set up a photographic studio and learned the Maya language. However he spent most of his time in the forests, accompanied by a few Maya to help clear the jungle from the ruins and carry Maler's photographic equipment. He started off visiting major sites already well-known, such as Chichen Itza and Uxmal, but zealously followed all leads and became the first to document many new ruins. At Chichen, he lived in the ruins for 3 months, and documented the site much more fully than had earlier visitors. Over the next years, Maler also made investigations of many remote sites in the el Petén region of Guatemala and along the course of the Usumacinta River.[3]  Maler became disgusted by the then common practice of 19th century antiquarians and archeologists of removing interesting sculptures from the sites to send to cities in Europe or North America. Maler noted the damage to the sites this often caused. He became dedicated to the notion that the ruins should be preserved intact, and wrote extensively to the Mexican government advocating that approach. Maler's views are now considered ahead of their time. Maler realized the importance of publishing his investigations, but had somewhat mixed success. The Peabody Institute of Harvard University arranged to publish his reports starting in 1898. A series of important books resulted, but the relationship between Maler and the Peabody was strained. Maler tried to insist that the books contain more minute detail and illustrations than the Peabody editors wished to include, and communications were difficult as Maler often left to make new expeditions in the forests and could not be contacted for months at a time for proofreading. The Peabody ended their agreement with Maler in 1909, although it took them until 1912 to finish the publication of the material they had received from him. The books are still an important reference in Maya studies. Maler ended his physically demanding expeditions in the jungles in 1905 and retired to his home in Mérida, Yucatán. In 1910 Maler made a trip to Europe in hopes of finding patrons for publishing more of his reports, but had no success other than to sell some of his photographs to the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. In his later years Teoberto Maler was known as something of a misanthrope. His money apparently gone due to some poor money investments and the economical crisis of 1907 in Yucatán, he made a modest living selling copies of his photographs to tourists and young archaeologists and giving lectures on Maya art and architecture at the Mérida school of fine arts. Maler died in Mérida, aged 75.[4] Many of his accounts were published posthumously, one batch in the 1930s, more in the 1970s and 1990s. Notes

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Teoberto Maler. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|