|

Synesthesia in art

The phrase synesthesia in art has historically referred to a wide variety of artists' experiments that have explored the co-operation of the senses (e.g. seeing and hearing; the word synesthesia is from the Ancient Greek σύν (syn), "together," and αἴσθησις (aisthēsis), "sensation") in the genres of visual music, music visualization, audiovisual art, abstract film, and intermedia (Campen 2007, Jewanski & Sidler 2006, Moritz 2003, 1999, Berman 1999, Maur 1999, Gage 1994, 1999). The age-old artistic views on synesthesia have some overlap with the current neuroscientific view on neurological synesthesia, but also some major differences, e.g. in the contexts of investigations, types of synesthesia selected, and definitions. While in neuroscientific studies synesthesia is defined as the elicitation of perceptual experiences in the absence of the normal sensory stimulation, in the arts the concept of synaesthesia is more often defined as the simultaneous perception of two or more stimuli as one gestalt experience (Campen 2009). The usage of the term synesthesia in art should, therefore, be differentiated from neurological synesthesia in scientific research. Synesthesia is by no means unique to artists or musicians. Only in the last decades have scientific methods become available to assess synesthesia in persons. For synesthesia in artists before that time one has to interpret (auto)biographical information. For instance, there has been debate on the neurological synesthesia of historical artists like Kandinsky and Scriabin (cf. Jewanski & Sidler 2006, Ione 2004, Dann 1999, Galeyev 2001). Additionally, Synesthetic art may refer to either art created by synesthetes or art created to elicit synesthetic experience in the general audience. DistinctionsWhen discussing synesthesia in art, a distinction needs to be made between two possible meanings:

These distinctions are not mutually exclusive, as, for example, art by a synesthete might also evoke synesthesia-like experiences in the viewer. However, it should not be assumed that all "synesthetic" art accurately reflects the synesthetic experience. For more on artists who either were synesthetes themselves, or who attempted to create synesthesia-like mappings in their art, see the list of people with synesthesia. Art by synesthetes Several contemporary visual artists have discussed their artistic process, and how synesthesia helps them in this, at length.[1] Linda Anderson, according to NPR considered "one of the foremost living memory painters", creates with oil crayons on fine-grain sandpaper representations of the auditory-visual synaesthesia she experiences during severe migraine attacks.[2][3] Carol Steen experiences multiple forms of synesthesia, including grapheme → color synesthesia, music → color synesthesia, and touch → color synesthesia. She most often uses her music → color synesthesia and touch → color synesthesia in creating her works of art, which often involves attempting to capture, select, and transmit her synesthetic experiences into her paintings. Steen describes how her synesthetic experience during an acupuncture session led to the creation of the painting Vision.

Rather than trying to create depictions of what she experiences, "Reflectionist" Marcia Smilack uses her synesthetic experience in guiding her towards creating images that are aesthetically pleasing and appealing to her. Smilack takes pictures of reflected objects, mostly using the surface of the water, and says of her photography style:

Anne Salz, a Dutch musician and visual artist, perceives music in colored patterns. She describes her painting inspired by Vivaldi's Concerto for Four Violins:

She explains that the painting is not a copy of what she hears; rather, when she listens to music, she perceives more colorful textures than she normally perceives and she is able to depict them in the painting. She also expresses the movement of the music, as its energy influences the pictorial composition. She explains how she perceives the painting:

Anne Patterson, a New York-based artist with a background in theatrical set design, describes the genesis of her installation of 20 miles of silk ribbons suspended from the vaulted ceiling arches of San Francisco's Grace Cathedral, which was inspired by a cello performance of Bach:

Brandy Gale, a Santa Cruz, California-based Canadian painter and photographer "experiences an involuntary joining or crossing of any of her senses – hearing, vision, taste, touch, smell and movement. Gale paints from life rather than from photographs and by exploring the sensory panorama of each locale attempts to capture, select, and transmit these personal experiences."[7]

In addition to her field work, Gale also paints live, sometimes performing her painting experience live before an audience with musical accompaniment, as she did at the 2013 EG Conference in Monterey, CA. with cellist Philip Sheppard,[9] at the Oakland Garden of Memory in June 2014 with her husband, guitarist and composer Henry Kaiser,[10] and with Kaiser and guitarist Ava Mendoza at The Stone in NYC.[11] Gale's 2014 solo exhibition Coastal Synaesthesia:Paintings and Photographs of Hawaii, Fiji and California was held at Gualala Arts Gallery, Gualala, CA.[12]

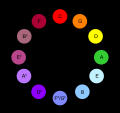

Art meant to evoke synesthetic associations Perhaps the most famous work which might be thought to evoke synesthesia-like experiences in a non-synesthete audience is the 1940 Disney film Fantasia, although it is unknown if this was intentional or not. Another classical example is the use of the color organ which would project colored lights along with the musical notes, to create a synesthetic experience in the audience (Campen 2007, Jewanski & Sidler 2006).  Wassily Kandinsky working in the 1920s, may not have been a synesthete, despite his fame for his synesthetic artwork. Many of his paintings and stage pieces were based upon a set and established system of correspondences between colors and the timbres of specific musical instruments. Kandinsky himself, however, stated that his correspondences between colors and musical timbres have no "scientific" basis, but were founded upon a combination of his own personal feelings, current prevailing cultural biases, and mysticism (Kandinsky 1994; Dann 1998; Riccò 1999, pp. 138–142 Jewanski & Sidler 2006, Campen 2007). History The interest in synesthesia is at least as old as Greek philosophy. One of the questions that the classic philosophers asked was if color (chroia, what we now call timbre) of music was a physical quality that could be quantified (Campen 2007, Gage 1994, Ferwerda & Struycken 2001, Jewanski 1999). The first known experiment to test correspondences between sound and color was conducted by the Milanese artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo at the end of the sixteenth century. He consulted with a musician at the court of Rudolph II in Prague to create a new experiment that sought to show the colors that accompany music. He decided to place different colored strips of painted paper on the gravicembalo, a keyboard instrument (Gage, 1994). He was also an artist who created strange portraits from unusual objects, such as Four Seasons in One Head. The problem of finding a mathematical system to explain the connection between music and color has both inspired and frustrated artists and scientists throughout the ages. The seventeenth-century physicist Isaac Newton tried to solve the problem by assuming that musical tones and color tones have frequencies in common. He attempted to link sound oscillations to respective light waves. According to Newton, the distribution of white light in a spectrum of colors is analogous to the musical distribution of tones in an octave. So, he identified seven discrete light entities, that he then matched to the seven discrete notes of an octave (Campen 2007, Peacock 1988). Color organsInspired by Newton’s theory of music-color correspondences, the French Jesuit Louis-Bertrand Castel designed a color harpsichord (clavecin oculaire) with colored strips of paper which rose above the cover of the harpsichord whenever a particular key was hit (Campen 2007, Franssen 1991). Renowned masters like Telemann and Rameau were actively engaged in the development of a clavecins oculaire. The invention of the gas light in the nineteenth century created new technical possibilities for the color organ. In England between 1869 and 1873, the inventor Frederick Kastner developed an organ that he named a Pyrophone. The British inventor Alexander Rimington, a professor in fine arts in London, documented the phrase ‘Colour-Organ’ for the first time in a patent application in 1893. Inspired by Newton’s idea that music and color are both grounded in vibrations, he divided the color spectrum into intervals analogous to musical octaves and attributed colors to notes. The same notes in a higher octave produced the same color tone but then in a lighter value (Peacock 1988). Around the turn of the century, concerts with light and musical instruments were given quite regularly. As most technical problems had been conquered, the psychological questions concerning the effects of these performances came to the fore. The Russian composer Alexander Scriabin was particularly interested in the psychological effects on the audience when they experienced sound and color simultaneously. His theory was that when the correct color was perceived with the correct sound, ‘a powerful psychological resonator for the listener’ would be created. His most famous synesthetic work, which is still performed today, is Prometheus, Poem of Fire. On the score of Prometheus, he wrote next to the instruments separate parts for the tastiere per luce, the color organ (Campen 2007, Galeyev 2001, Gleich 1963). Musical paintingsIn the second half the nineteenth century, a tradition of musical paintings began to appear that influenced symbolist painters (Campen 2007, Van Uitert 1978). In the first decades of the twentieth century, a German artist group called The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) executed synesthetic experiments that involved a composite group of painters, composers, dancers and theater producers. The group focused on the unification of the arts by means of "Total Works of Art" (Gesamtkunstwerk) (Von Maur 2001, Hahl-Koch 1985, Ione 2004). Kandinsky's theory of synesthesia, as formulated in the booklet "Concerning the Spiritual in Art" (1910), helped to shape the ground for these experiments. Kandinsky was not the only artist at this time with an interest in synesthetic perception. A study of the art at the turn of the century reveals in the work of almost every progressive or avant-garde artist an interest in the correspondences of music and visual art. Modern artists experimented with multi-sensory perception like the simultaneous perception of movement in music and film (Von Maur 2001, Heyrman 2003). Visual musicStarting in the late 1950s, electronic music and electronic visual art have co-existed in the same digital medium (Campen 2007, Collopy 2000, Jewanski & Sidler 2006, Moritz 2003). Since that time, the interaction of these fields of art has increased tremendously. Nowadays, students of art and music have digital software at their disposal that uses both musical and visual imagery. Given the capability of the Internet to publish and share digital productions, this has led to an enormous avalanche of synesthesia-inspired art on the Internet (Campen 2007) (cf. website RhythmicLight.com on the history of visual music). For instance, Stephen Malinowski and Lisa Turetsky from Berkeley, California wrote a software program, entitled the Music Animation Machine, that translates and shows music pieces in colored measures. Synesthetic artistsWith today’s knowledge and testing apparatus, it can be determined with more certainty if contemporary artists are synesthetic. The scientific evidence in artists is often insufficient to support the claims of synesthesia, and caution is warranted in evaluating artwork predicated on such claims. By interviewing these artists, one may get some insight into the process of painting music (cf. Steen, Smilack, Salz). Some contemporary artists are active members of synesthesia associations in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Spain, Belgium and other countries (cf. Arte Citta) [1]. In and outside these associations that house scientists and artists, the exchange of ideas and collaborations between artists and scientists has grown rapidly in the last decades (cf. the Leonardo online bibliography Synesthesia in Art and Science) [2], and this is only a small selection of synesthetic work in the arts. New artistic projects on synesthesia are appearing every year. For instance they capture their synesthetic perceptions in painting, photographs, textile work, and sculptures. Beside these ‘classical’ materials of making art, an even larger production of synesthesia-inspired works is noticed in the field of digital art (Campen 2007). Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|