|

Sylvester–Gallai theorem

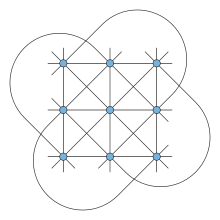

The Sylvester–Gallai theorem in geometry states that every finite set of points in the Euclidean plane has a line that passes through exactly two of the points or a line that passes through all of them. It is named after James Joseph Sylvester, who posed it as a problem in 1893, and Tibor Gallai, who published one of the first proofs of this theorem in 1944. A line that contains exactly two of a set of points is known as an ordinary line. Another way of stating the theorem is that every finite set of points that is not collinear has an ordinary line. According to a strengthening of the theorem, every finite point set (not all on one line) has at least a linear number of ordinary lines. An algorithm can find an ordinary line in a set of points in time . HistoryThe Sylvester–Gallai theorem was posed as a problem by J. J. Sylvester (1893). Kelly (1986) suggests that Sylvester may have been motivated by a related phenomenon in algebraic geometry, in which the inflection points of a cubic curve in the complex projective plane form a configuration of nine points and twelve lines (the Hesse configuration) in which each line determined by two of the points contains a third point. The Sylvester–Gallai theorem implies that it is impossible for all nine of these points to have real coordinates.[1] H. J. Woodall (1893a, 1893b) claimed to have a short proof of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem, but it was already noted to be incomplete at the time of publication. Eberhard Melchior (1941) proved the theorem (and actually a slightly stronger result) in an equivalent formulation, its projective dual. Unaware of Melchior's proof,[2] Paul Erdős (1943) again stated the conjecture, which was subsequently proved by Tibor Gallai, and soon afterwards by other authors.[3] In a 1951 review, Erdős called the result "Gallai's theorem",[4] but it was already called the Sylvester–Gallai theorem in a 1954 review by Leonard Blumenthal.[5] It is one of many mathematical topics named after Sylvester. Equivalent versionsThe question of the existence of an ordinary line can also be posed for points in the real projective plane RP2 instead of the Euclidean plane. The projective plane can be formed from the Euclidean plane by adding extra points "at infinity" where lines that are parallel in the Euclidean plane intersect each other, and by adding a single line "at infinity" containing all the added points. However, the additional points of the projective plane cannot help create non-Euclidean finite point sets with no ordinary line, as any finite point set in the projective plane can be transformed into a Euclidean point set with the same combinatorial pattern of point-line incidences. Therefore, any pattern of finitely many intersecting points and lines that exists in one of these two types of plane also exists in the other. Nevertheless, the projective viewpoint allows certain configurations to be described more easily. In particular, it allows the use of projective duality, in which the roles of points and lines in statements of projective geometry can be exchanged for each other. Under projective duality, the existence of an ordinary line for a set of non-collinear points in RP2 is equivalent to the existence of an ordinary point in a nontrivial arrangement of finitely many lines. An arrangement is said to be trivial when all its lines pass through a common point, and nontrivial otherwise; an ordinary point is a point that belongs to exactly two lines.[2]  Arrangements of lines have a combinatorial structure closely connected to zonohedra, polyhedra formed as the Minkowski sum of a finite set of line segments, called generators. In this connection, each pair of opposite faces of a zonohedron corresponds to a crossing point of an arrangement of lines in the projective plane, with one line for each generator. The number of sides of each face is twice the number of lines that cross in the arrangement. For instance, the elongated dodecahedron shown is a zonohedron with five generators, two pairs of opposite hexagon faces, and four pairs of opposite parallelogram faces. In the corresponding five-line arrangement, two triples of lines cross (corresponding to the two pairs of opposite hexagons) and the remaining four pairs of lines cross at ordinary points (corresponding to the four pairs of opposite parallelograms). An equivalent statement of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem, in terms of zonohedra, is that every zonohedron has at least one parallelogram face (counting rectangles, rhombuses, and squares as special cases of parallelograms). More strongly, whenever sets of points in the plane can be guaranteed to have at least ordinary lines, zonohedra with generators can be guaranteed to have at least parallelogram faces.[6] ProofsThe Sylvester–Gallai theorem has been proved in many different ways. Gallai's 1944 proof switches back and forth between Euclidean and projective geometry, in order to transform the points into an equivalent configuration in which an ordinary line can be found as a line of slope closest to zero; for details, see Borwein & Moser (1990). The 1941 proof by Melchior uses projective duality to convert the problem into an equivalent question about arrangements of lines, which can be answered using Euler's polyhedral formula. Another proof by Leroy Milton Kelly shows by contradiction that the connecting line with the smallest nonzero distance to another point must be ordinary. And, following an earlier proof by Steinberg, H. S. M. Coxeter showed that the metric concepts of slope and distance appearing in Gallai's and Kelly's proofs are unnecessarily powerful, instead proving the theorem using only the axioms of ordered geometry. Kelly's proof This proof is by Leroy Milton Kelly. Aigner & Ziegler (2018) call it "simply the best" of the many proofs of this theorem.[7] Suppose that a finite set of points is not all collinear. Define a connecting line to be a line that contains at least two points in the collection. By finiteness, must have a point and a connecting line that are a positive distance apart such that no other point-line pair has a smaller positive distance. Kelly proved that is ordinary, by contradiction.[7] Assume that is not ordinary. Then it goes through at least three points of . At least two of these are on the same side of , the perpendicular projection of on . Call them and , with being closest to (and possibly coinciding with it). Draw the connecting line passing through and , and the perpendicular from to on . Then is shorter than . This follows from the fact that and are similar triangles, one contained inside the other.[7] However, this contradicts the original definition of and as the point-line pair with the smallest positive distance. So the assumption that is not ordinary cannot be true, QED.[7] Melchior's proofIn 1941 (thus, prior to Erdős publishing the question and Gallai's subsequent proof) Melchior showed that any nontrivial finite arrangement of lines in the projective plane has at least three ordinary points. By duality, this results also says that any finite nontrivial set of points on the plane has at least three ordinary lines.[8] Melchior observed that, for any graph embedded in the real projective plane, the formula must equal , the Euler characteristic of the projective plane. Here , , and are the number of vertices, edges, and faces of the graph, respectively. Any nontrivial line arrangement on the projective plane defines a graph in which each face is bounded by at least three edges, and each edge bounds two faces; so, double counting gives the additional inequality . Using this inequality to eliminate from the Euler characteristic leads to the inequality . But if every vertex in the arrangement were the crossing point of three or more lines, then the total number of edges would be at least , contradicting this inequality. Therefore, some vertices must be the crossing point of only two lines, and as Melchior's more careful analysis shows, at least three ordinary vertices are needed in order to satisfy the inequality .[8] As Aigner & Ziegler (2018) note, the same argument for the existence of an ordinary vertex was also given in 1944 by Norman Steenrod, who explicitly applied it to the dual ordinary line problem.[9] Melchior's inequalityBy a similar argument, Melchior was able to prove a more general result. For every , let be the number of points to which lines are incident. Then[8] or equivalently, AxiomaticsH. S. M. Coxeter (1948, 1969) writes of Kelly's proof that its use of Euclidean distance is unnecessarily powerful, "like using a sledge hammer to crack an almond". Instead, Coxeter gave another proof of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem within ordered geometry, an axiomatization of geometry in terms of betweenness that includes not only Euclidean geometry but several other related geometries.[10] Coxeter's proof is a variation of an earlier proof given by Steinberg in 1944.[11] The problem of finding a minimal set of axioms needed to prove the theorem belongs to reverse mathematics; see Pambuccian (2009) for a study of this question. The usual statement of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem is not valid in constructive analysis, as it implies the lesser limited principle of omniscience, a weakened form of the law of excluded middle that is rejected as an axiom of constructive mathematics. Nevertheless, it is possible to formulate a version of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem that is valid within the axioms of constructive analysis, and to adapt Kelly's proof of the theorem to be a valid proof under these axioms.[12] Finding an ordinary lineKelly's proof of the existence of an ordinary line can be turned into an algorithm that finds an ordinary line by searching for the closest pair of a point and a line through two other points. Mukhopadhyay & Greene (2012) report the time for this closest-pair search as , based on a brute-force search of all triples of points, but an algorithm to find the closest given point to each line through two given points, in time , was given earlier by Edelsbrunner & Guibas (1989), as a subroutine for finding the minimum-area triangle determined by three of a given set of points. The same paper of Edelsbrunner & Guibas (1989) also shows how to construct the dual arrangement of lines to the given points (as used in Melchior and Steenrod's proof) in the same time, , from which it is possible to identify all ordinary vertices and all ordinary lines. Mukhopadhyay, Agrawal & Hosabettu (1997) first showed how to find a single ordinary line (not necessarily the one from Kelly's proof) in time , and a simpler algorithm with the same time bound was described by Mukhopadhyay & Greene (2012). The algorithm of Mukhopadhyay & Greene (2012) is based on Coxeter's proof using ordered geometry. It performs the following steps:

As the authors prove, the line returned by this algorithm must be ordinary. The proof is either by construction if it is returned by step 4, or by contradiction if it is returned by step 7: if the line returned in step 7 were not ordinary, then the authors prove that there would exist an ordinary line between one of its points and , but this line should have already been found and returned in step 4.[13] The number of ordinary lines While the Sylvester–Gallai theorem states that an arrangement of points, not all collinear, must determine an ordinary line, it does not say how many must be determined. Let be the minimum number of ordinary lines determined over every set of non-collinear points. Melchior's proof showed that . de Bruijn and Erdős (1948) raised the question of whether approaches infinity with . Theodore Motzkin (1951) confirmed that it does by proving that . Gabriel Dirac (1951) conjectured that , for all values of . This is often referred to as the Dirac–Motzkin conjecture; see for example Brass, Moser & Pach (2005, p. 304). Kelly & Moser (1958) proved that .  Dirac's conjectured lower bound is asymptotically the best possible, as the even numbers greater than four have a matching upper bound . The construction, due to Károly Böröczky, that achieves this bound consists of the vertices of a regular -gon in the real projective plane and another points (thus, ) on the line at infinity corresponding to each of the directions determined by pairs of vertices. Although there are pairs of these points, they determine only distinct directions. This arrangement has only ordinary lines, the lines that connect a vertex with the point at infinity collinear with the two neighbors of . As with any finite configuration in the real projective plane, this construction can be perturbed so that all points are finite, without changing the number of ordinary lines.[14] For odd , only two examples are known that match Dirac's lower bound conjecture, that is, with One example, by Kelly & Moser (1958), consists of the vertices, edge midpoints, and centroid of an equilateral triangle; these seven points determine only three ordinary lines. The configuration in which these three ordinary lines are replaced by a single line cannot be realized in the Euclidean plane, but forms a finite projective space known as the Fano plane. Because of this connection, the Kelly–Moser example has also been called the non-Fano configuration.[15] The other counterexample, due to McKee,[14] consists of two regular pentagons joined edge-to-edge together with the midpoint of the shared edge and four points on the line at infinity in the projective plane; these 13 points have among them 6 ordinary lines. Modifications of Böröczky's construction lead to sets of odd numbers of points with ordinary lines.[16] Csima & Sawyer (1993) proved that except when is seven. Asymptotically, this formula is already of the proven upper bound. The case is an exception because otherwise the Kelly–Moser construction would be a counterexample; their construction shows that . However, were the Csima–Sawyer bound valid for , it would claim that . A closely related result is Beck's theorem, stating a tradeoff between the number of lines with few points and the number of points on a single line.[17] Ben Green and Terence Tao showed that for all sufficiently large point sets (that is, for some suitable choice of ), the number of ordinary lines is indeed at least . Furthermore, when is odd, the number of ordinary lines is at least , for some constant . Thus, the constructions of Böröczky for even and odd (discussed above) are best possible. Minimizing the number of ordinary lines is closely related to the orchard-planting problem of maximizing the number of three-point lines, which Green and Tao also solved for all sufficiently large point sets.[18] In the dual setting, where one is looking for ordinary points, one can consider the minimum number of ordinary points in an arrangement of pseudolines. In this context, the Csima-Sawyer lower bound is still valid,[19] though it is not known whether the Green and Tao asymptotic bound still holds. The number of connecting linesAs Paul Erdős observed, the Sylvester–Gallai theorem immediately implies that any set of points that are not collinear determines at least different lines. This result is known as the De Bruijn–Erdős theorem. As a base case, the result is clearly true for . For any larger value of , the result can be reduced from points to points, by deleting an ordinary line and one of the two points on it (taking care not to delete a point for which the remaining subset would lie on a single line). Thus, it follows by mathematical induction. The example of a near-pencil, a set of collinear points together with one additional point that is not on the same line as the other points, shows that this bound is tight.[16] GeneralizationsThe Sylvester–Gallai theorem has been generalized to colored point sets in the Euclidean plane, and to systems of points and lines defined algebraically or by distances in a metric space. In general, these variations of the theorem consider only finite sets of points, to avoid examples like the set of all points in the Euclidean plane, which does not have an ordinary line. Colored pointsA variation of Sylvester's problem, posed in the mid-1960s by Ronald Graham and popularized by Donald J. Newman, considers finite planar sets of points (not all in a line) that are given two colors, and asks whether every such set has a line through two or more points that are all the same color. In the language of sets and families of sets, an equivalent statement is that the family of the collinear subsets of a finite point set (not all on one line) cannot have Property B. A proof of this variation was announced by Theodore Motzkin but never published; the first published proof was by Chakerian (1970).[20] Non-real coordinates Just as the Euclidean plane or projective plane can be defined by using real numbers for the coordinates of their points (Cartesian coordinates for the Euclidean plane and homogeneous coordinates for the projective plane), analogous abstract systems of points and lines can be defined by using other number systems as coordinates. The Sylvester–Gallai theorem does not hold for geometries defined in this way over finite fields: for some finite geometries defined in this way, such as the Fano plane, the set of all points in the geometry has no ordinary lines.[7] The Sylvester–Gallai theorem also does not directly apply to geometries in which points have coordinates that are pairs of complex numbers or quaternions, but these geometries have more complicated analogues of the theorem. For instance, in the complex projective plane there exists a configuration of nine points, Hesse's configuration (the inflection points of a cubic curve), in which every line is non-ordinary, violating the Sylvester–Gallai theorem. Such a configuration is known as a Sylvester–Gallai configuration, and it cannot be realized by points and lines of the Euclidean plane. Another way of stating the Sylvester–Gallai theorem is that whenever the points of a Sylvester–Gallai configuration are embedded into a Euclidean space, preserving colinearities, the points must all lie on a single line, and the example of the Hesse configuration shows that this is false for the complex projective plane. However, Kelly (1986) proved a complex-number analogue of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem: whenever the points of a Sylvester–Gallai configuration are embedded into a complex projective space, the points must all lie in a two-dimensional subspace. Equivalently, a set of points in three-dimensional complex space whose affine hull is the whole space must have an ordinary line, and in fact must have a linear number of ordinary lines.[21] Similarly, Elkies, Pretorius & Swanepoel (2006) showed that whenever a Sylvester–Gallai configuration is embedded into a space defined over the quaternions, its points must lie in a three-dimensional subspace. MatroidsEvery set of points in the Euclidean plane, and the lines connecting them, may be abstracted as the elements and flats of a rank-3 oriented matroid. The points and lines of geometries defined using other number systems than the real numbers also form matroids, but not necessarily oriented matroids. In this context, the result of Kelly & Moser (1958) lower-bounding the number of ordinary lines can be generalized to oriented matroids: every rank-3 oriented matroid with elements has at least two-point lines, or equivalently every rank-3 matroid with fewer two-point lines must be non-orientable.[22] A matroid without any two-point lines is called a Sylvester matroid. Relatedly, the Kelly–Moser configuration with seven points and only three ordinary lines forms one of the forbidden minors for GF(4)-representable matroids.[15] Distance geometryAnother generalization of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem to arbitrary metric spaces was conjectured by Chvátal (2004) and proved by Chen (2006). In this generalization, a triple of points in a metric space is defined to be collinear when the triangle inequality for these points is an equality, and a line is defined from any pair of points by repeatedly including additional points that are collinear with points already added to the line, until no more such points can be added. The generalization of Chvátal and Chen states that every finite metric space has a line that contains either all points or exactly two of the points.[23] Notes

References

External links

|