|

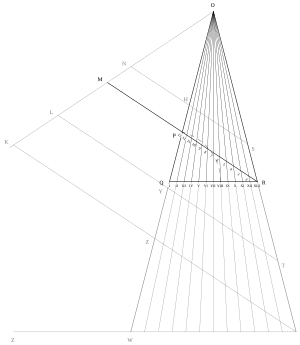

Strähle construction Strähle's construction is a geometric method for determining the lengths for a series of vibrating strings with uniform diameters and tensions to sound pitches in a specific rational tempered musical tuning. It was first published in the 1743 Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences by Swedish master organ maker Daniel Stråhle (1700–1746). The Academy's secretary Jacob Faggot appended a miscalculated set of pitches to the article, and these figures were reproduced by Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg in Versuch über die musikalische Temperatur in 1776. Several German textbooks published about 1800 reported that the mistake was first identified by Christlieb Benedikt Funk in 1779, but the construction itself appears to have received little notice until the middle of the twentieth century when tuning theorist J. Murray Barbour presented it as a good method for approximating equal temperament and similar exponentials of small roots, and generalized its underlying mathematical principles. It has become known as a device for building fretted musical instruments through articles by mathematicians Ian Stewart and Isaac Jacob Schoenberg, and is praised by them as a unique and remarkably elegant solution developed by an unschooled craftsman. The name "Strähle" used in recent English language works appears to be due to a transcription error in Marpurg's text, where the old-fashioned diacritic raised "e" was substituted for the raised ring.[1] BackgroundDaniel P. Stråhle was active as an organ builder in central Sweden in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. He had worked as a journeyman for the important Stockholm organ builder Johan Niclas Cahman and, in 1741, four years after Cahman's death, Stråhle was granted his privilege for organ making. According to the system in force in Sweden at the time a privilege, a granted monopoly which was held by only a few of the most established makers of each type of musical instruments, gave him the legal right to build and repair organs, as well as to train and examine workers, and it also served as a guarantee of the quality of the work and education of the maker.[2] An organ by him from 1743 is preserved in its original condition at the chapel at Strömsholm Palace;[3] he is also known to have made clavichords, and a notable example with an unusual string scale and construction signed by him and dated 1738 is owned by the Stockholm Music Museum.[4] His apprentices included his nephew Petter Stråhle and Jonas Gren, partners in the famous Stockholm organ builders Gren & Stråhle,[5] and according to Abraham Abrahamsson Hülphers in his book Historisk Afhandling om Musik och Instrumenter published in 1773, Stråhle himself had studied mechanics (which has been assumed to have included mathematics[6]) with Swedish Academy of Science founding member Christopher Polhem.[7] He died in 1746 at Lövstabruk in northern Uppland. Stråhle published his construction as a "new invention, to determine the Temperament in tuning, for the pitches of the clavichord and similar instruments" in an article that appeared in the fourth volume of the proceedings of the newly formed Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which included articles by prominent scholars and Academy members Polhem, Carl Linnaeus, Carl Fredrik Mennander, Augustin Ehrensvärd, and Samuel Klingenstierna. According to organologist Eva Helenius musical tuning was a subject of intense debate in the Academy during the 1740s,[8] and though Stråhle himself was not a member his was the third article on practical musical topics published by the Academy—the first two were by amateur musical instrument maker, minister, and Academy member Nils Brelin[9] which related inventions applicable to harpsichords and clavichords.[10] Stråhle wrote in his article that he had developed the method with "some thought and a great number of attempts" for the purpose of creating a gauge for the lengths of the strings in the temperament which he described as that which made the tempering ("sväfningar") mildest for the ear, as well comprising as the most useful and even arrangement of the pitches. His instructions produce an irregular tuning with a range of tempered intervals similar to better known tunings published during the same period, but he provided no further comments or description about the tuning itself; today it is generally considered to be an approximation of equal temperament.[11] He also did not elaborate upon any advantages of his construction, which can produce accurate and repeatable results without calculations or measurement with only a straightedge and dividers; he described the construction in only five steps, and it is less iterative than arithmetic methods described by Dom Bédos de Celles method for determining organ pipe lengths in just intonation or Vincenzo Galilei for determining string fret positions in approximate equal temperament, and geometrical methods such as those described by Gioseffo Zarlino and Marin Mersenne—all of which are much better known than Stråhle's. Stråhle concluded by stating that he had applied the system to a clavichord, although the tuning as well as the method of determining a set of sounding lengths can be used for many other musical instruments, but there is little evidence showing whether it was put into more widespread practice other than the two examples described in the article, and whose whereabouts today are unknown. Construction Stråhle instructed first to draw a line segment QR of a convenient length divided in twelve equal parts, with points labeled I through XIII. QR is then used as the base of an isosceles triangle with sides OQ and OR twice as long as QR, and rays drawn from vertex O through each of the numbered points on the base. Finally a line is drawn from vertex R at an angle through a point P on the opposite leg of the triangle seven units from Q to a point M, located at twice the distance from R as P. The length of MR gives the length of the lowest sounding pitch, and the length of MP the highest of the string lengths generated by the construction, and the sounding lengths between them are determined by the distances from M to the intersections of MR with lines O I through O XII, at points labeled 1 through 12. Stråhle wrote that he had named the line PR "Linea Musica", which Helenius noted was a term Polhem had used in an undated but earlier manuscript now located at the Linköping Stifts- och Landsbibliotek and which is accompanied by notes from composer and geometer Harald Vallerius (1646–1716) and Stråhle's former employer J. N. Cahman.[8] Stråhle also showed line segments parallel to MR through points NHS, LYT, and KZV in order to illustrate how once created the construction could be scaled to accommodate different starting pitches. Stråhle stated at the conclusion of the article that he had implemented the string scale in the highest three octaves of a clavichord, although it is unclear whether this section would have been strung all with the same gauge wire under equal tension like the monochord which he wrote it resembled, and whose construction he described in more detail. He only described an indirect method of setting its tuning, however, requiring that he first establish reference pitches by transferring the corresponding string lengths to the movable bridges on a keyed thirteen string monochord whose open strings had been previously tuned in unison.a Faggot's numerical representation The article following Stråhle's was a mathematical treatment of it by Jacob Faggot (1699–1777), then secretary of the Academy of Sciences and future director of the Surveying Office, who in the same volume also contributed articles on a weight measure for lye and methods for calculating the volume of barrels. Faggot was one of the first members of the Academy, and had also been member of a special commission on weights and measures.[12] He apparently was not a musician, though Helenius described he was interested in musical topics from a mathematical perspective and documented that he periodically came in contact with musical instrument makers through the Academy.[13] Helenius also presented a theory that Faggot had a more active, if indirect and posthumous influence on the construction of musical instruments in Sweden, claiming that he may have suggested the long tenor strings used in two experimental instruments built by Johan Broman in 1756 which she proposed influenced the type of clavichord built in Sweden in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[14]

In his analysis of Stråhle's article Faggot outlined the trigonometric steps he had used to calculate the sounding lengths of the individual pitches, for the purpose of comparing the new tuning produced by Stråhle's method, against a tuning with pure thirds, fourths and fifths (labeled "N. 1" in the table), and equal temperament, which he called only "an older temperament and [which] is introduced in Mr. Mattheson's Critica Musica" ("N. 2"), He intended the resulting set of figures to show whether "the tuning of the pitches, following the previously described invention, satisfies the ear with pleasant sounds and with better evenness, in the Musical pitches on a keyboard instrument, and therefore teaches understanding better can judge than the old and previously known manner of tuning, when the eye can see what the ear hears."b Both articles were reproduced in a German edition of the Academy's proceedings published in 1751,[16] and a table of Faggot's calculated string lengths was subsequently included by Marpurg on his 1776 Versuch über die musikalische Temperatur,[1] who wrote that he accepted their accuracy but that rather than accomplishing "Strähle"'s stated goal, the tuning represented an unequal temperament "not even of the tolerable type."c The sounding lengths calculated by Faggot are substantially different from what would be produced according to Stråhle's instructions, a fact which appears to have been first published by Christlieb Benedict Funk in Dissertatio de Sono et Tono in 1779,[17] and the tuning he created includes intervals tuned outside of the range conventionally used in Western art music. Funk is credited the observation of this discrepancy in Gehler's Physikalisches Wörterbuch in 1791,[18] and Fischer's Physikalisches Wörterbuch in 1804,[19] and the error was pointed out by Ernst Chladni in Die Akustik in 1830.[20] No similar comments appear to have been published in Sweden during the same period. These works report Faggot's mistake as the result of having used a value from the tangent instead of the sine column from the logarithmic tables. The error itself consisted of making the angle of RP about seven degrees too great, which caused the effective length of QP to increase to 8.605. This greatly exaggerated the errors of the temperament compared to the tunings he presented alongside it, although it is not clear whether Faggot observed these apparent defects as he made no further comments about Stråhle's construction or temperament in the article.  The tuningThe tuning produced following Stråhle's instructions is a rational temperament with a range of fifths from 696 to 704 cents, which is from about one cent flatter than a meantone fifth to two cents sharp of just 3:2; the range of major thirds is from 396 cents to 404 cents, or ten cents sharp of just 5/4 to three cents flat of Pythagorean 81/64. These intervals fall within what is considered to have been acceptable but there is no distribution of better thirds to more frequently used keys that characterize what are today the most popular of the tunings published in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which are known as well temperaments. The best fifth is pure in the key of F♯—or the pitch given by MB—which has a 398 cent third, and the best third is in the key E, which has a 697 cent fifth; the best combination of the two intervals is in the key of F and the worst combination is in the key of B♭. Barbour's algebraic representation and geometric constructionJ. Murray Barbour brought new attention to Stråhle's construction along with Faggot's treatment of it in the 20th century. Introduced in the context of Marpurg, he included an overview of it alongside the more famous methods of determining string lengths in his 1951 book Tuning and Temperament where he characterized the tuning as an "approximation for equal temperament". He also demonstrated how close Stråhle's construction was to the best approximation the method could provide, which reduces the maximum errors in major thirds and fifths by about half a cent and is accomplished by substituting 7.028 for the length of QP. Barbour presented a more complete analysis of the construction in "A Geometrical Approximation to the Roots of Numbers" published six years later in American Mathematical Monthly.[21] He reviewed Faggot's error and its consequences, and then derived Stråhle's construction algebraically using similar triangles. This takes the generalized form Using the values from Stråhle's instructions this becomes Letting so that leads to a form of the first formula that is more useful for calculation Barbour then described a generalized construction using the easily obtained mean proportional for the length of MB that avoids most of the specific angles and lengths required in the original. For musical applications it is simpler and its results are slightly more uniform than Stråhle's, and it has the advantage of producing the desired string lengths without additional scaling. He instructed to first draw the line MR corresponding to the larger of the two numbers with MP the smaller, and to construct their mean proportional at MB. The line that will carry the divisions is drawn from R at any acute angle to MR, and perpendicular to it a line is drawn through B, which intersects the line to be divided at A, and RA is extended to Q such that RA=AQ. A line is drawn from Q through P, intersecting the line through BA at O, and a line drawn from O to R. The construction is completed by dividing QR and drawing rays from O through each of the divisions. Barbour concluded with a discussion of the pattern and magnitude of the errors produced by the generalized construction when used to approximate exponentials of different roots, stating that his method "is simple and works exceedingly well for small numbers". For roots from 1 to 2 the error is less than 0.13%—about 2 cents when N=2— with maxima around m=0.21 and m=0.79. The error curve appears roughly sinusoidal and for this range of N can be approximated by about 99% by fitting the curve obtained for N=1, . The error increases rapidly for larger roots, for which Barbour considered the method inappropriate; the error curve resembles the form with maxima moving closer to m= 0 and m=1 as N increases. Schoenberg's refinements of Barbour's methodsThe paper was published with two notes added by its referee, Isaac Jacob Schoenberg. He observed that the formula derived by Barbour was a fractional linear transformation and so called for a perspectivity, and that since three pairs of corresponding points on the two lines uniquely determined a projective correspondence Barbour's condition that OA be perpendicular to QR was irrelevant. The omission of this step allows a more convenient selection of length for QR, and reduces the number of operations. Schoenberg also noted that Barbour's equation could be viewed as an interpolation of the exponential curve through the three points m=0, m=1/2, and m=1, which he expanded upon in a short paper titled "On the Location of the Frets on the Guitar" published in American Mathematical Monthly in 1976.[22] This article concluded with a brief discussion of Stråhle's fortuitous use of for the half-octave, which is one of the convergents of the continued fraction expansion of the , and the best rational approximation of it for the size of the denominator. Stewart and continued fractionsThe use of fractional approximations of in Stråhle's construction was expanded upon by Ian Stewart, who wrote about the construction in "A Well Tempered Calculator" in his 1992 book Another Fine Math You've Got Me Into... [23] as well as "Faggot's Fretful Fiasco" included in Music and Mathematics published in 2006. Stewart considered the construction from the standpoint of projective geometry, and derived the same formulas as Barbour by treating it from the start as a fractional linear function, of the form , and he pointed out that the approximation for implicit in the construction is , which is the next lower convergent from the half octave it produces. This is the consequence of the function simplifying to for m=0.5 where is the generating approximation. Similar methods applied to musical instrumentsThe geometric and arithmetic methods for dividing monochords as well as musical instrument fretboards compiled by Barbour were for the stated purpose of illustrating the different tunings each represents or implies, and Schoenberg's and Stewart's works retained similar focus and references. Three textbooks on piano building that are not included by them show similar constructions to Stråhle's for designing new instruments but treat the tuning of their pitches independently; both constructions employ a non-perpendicular form as suggested by Schoenberg's observation in Barbour's "A Geometrical approximation to the Roots of Numbers", and one achieves optimal results while the other demonstrates an application with a root other than 2. KützingCarl Kützing, an organ and piano maker in Bern during the middle of the 19th century wrote in his first book on piano design, Theoretisch-praktisches Handbuch der Fortepiano-Baukunst from 1833, that he devised a simple method of determining the sounding lengths in an octave after reading of the different geometric constructions described in an issue of Marpurg's Historisch-kritischen Beitragen zur Aufnahme der Musik; he stated that the divisions would be very accurate and that the construction could be used for fretting guitars. Kützing introduced the construction following a description of a large sector to be made for the same purpose. He did not include either method in Das Wissenschaftliche der Fortepiano-Baukunst published eleven years later, where he calculated lengths using approximately 18:35 ratios between octave lengths and proposed a new method with a non-continuous curve adjusted for actual wire diameters in order to reduce tonal differences from jumps in tension.[24] Kützing instructed to extend a line segment bc—representing a known sounding length—at 45 degrees to the line ba, and from its octave at point d located midway between b and c, to extend a line perpendicular to ba intersecting it at e, then to divide de into 12 equal parts. The point a on ab is located by transferring the lengths of de, db, from e away from b, and rays extended from a through the points dividing de and intersecting bc to locate the different endpoints of the string lengths from c.[25] This arrangement is equivalent to using the mean proportional to locate a. A re-labeled diagram with instructions was included in a pamphlet printed by England's largest piano manufacturers John Broadwood & Sons to accompany their display at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, where they described it as "a practical method of finding the lengths of Strings, for every note of the Octave on equal temperament; so that with wire of the same size the tension on each note shall be the same."[26] It was also reproduced, alongside a sector, by Giacomo Sievers, a Russian-born piano maker working in Naples, in his 1868 book Il Pianoforte, where he claimed it was the best practical method for determining sounding lengths of strings in a piano. Like Broadwood, Sievers did not describe its source or extent of its use, and did not explain any theory behind it. He also did not suggest it had any use beyond designing pianos.[27] WolfendenEnglish piano maker Samuel Wolfenden presented a construction for determining all but the lowest sounding plain string lengths in a piano in A Treatise on the Art of Pianoforte Construction published in 1916; like Sievers, he did not explain whether this was an original procedure or one in common use, commenting only that it was "a very practical method of determining string lengths, and in past years I used it altogether". He added that at the time of writing he found calculating the lengths directly "somewhat easier" and had preceded the description with a table of computed lengths for the top five octaves of a piano.[28] He included frequencies in equal temperament, but only published aural tuning instructions in his 1927 supplement. Wolfenden explicitly advocated equalizing the tension of the plain strings which he proposed to accomplish in the upper range by combining a 9:17 ratio between octave lengths with a uniform change in string diameters (achieving slightly more consistent results over the otherwise similar system published by Siegfried Hansing in 1888[29]), in contrast to Sievers scale whose stringing schedule results in higher tension for the thicker, lower sounding pitches. Like Sievers, Wolfenden constructed all of the sounding lengths on a single segment at 45 degrees from the base lines for the rays, starting with points located for each C in the range designed at 54, 102, 192.5, 364, and 688mm from the upper point. The four vertices for the rays are then located by the intersections of the horizontal base lines extended from the lower C in each octave with a second line angled from the upper starting point for the string line, however, which he specified should both be at 51.5 degrees to the base lines and that the base lines have a 35:13 ratio with the difference between the two octave lengths. Wolfenden's method approximates with roughly 1.3775, and is equivalent to in Barbour's form. Compensating for its smaller octaves this produces 596 cent half octaves, an error of about 1mm at note F4 (f′) compared with his calculated figures. Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||