|

Speri (region)

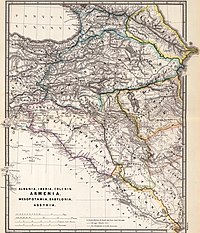

Speri, also known as Sper (Armenian: Սպեր Sber or Sper, Georgian: სპერი Speri),[1][2][3] is a historical region now part of the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. It was centered in the upper reaches of the valley of the Çoruh River, its probable capital was the town of İspir, or Syspiritus as indicated on the map next to the Byzantine-Sassanid border, and it originally extended as far west as the town of Bayburt and the Bayburt plains. OriginSper was a part of ancient confederation Hayasa-Azzi on lands of Armenian Highland, in 2nd millennium BC.[4] The name Speri is thought by some to be derived from Saspers.[5] According to the most widespread theory, they were a Kartvelian tribe.[6][7][8][9] However, their origins have also been attributed to Scythian people.[10] HistoryAntiquity In 2nd millennium BC on lands of Sper was an ancient confederation Hayasa-Azzi who were the Armenians.[11][12][13][14][15]

Late antique Sper was part of Armenia and is probably the Syspiritis of classical authors.[17] Syspiritis is mentioned in Strabo's Geographica: one of two areas (the other being Acilisene) settled by followers of "Armenus of Armenium", the eponymous founder of the Armenian race. Strabo also mentions "mines of gold in the Hyspiratis".[18][19][A]  After the 380s partition of Armenia into Roman and Sasanian client states, Sper was one of nine districts forming the territory of the Armenian kingdom of Arshak III. Sper at that period was a principality, the ancestral domain of the Bagratuni clan. Their capital was the fortress of Smbatavan or Smbataberd, which may have been located either at Bayburt or Ispir. In the northern part of the principality was a territory lived in by non-Armenian people called Chalybes, whose name was preserved in the alternative Armenian name for the Sper valley: Khaghto Dzor (Chaldian Valley).[21] After Arshak's death, in 390 his kingdom was annexed by Rome and turned into a Roman province called Inner Armenia. During the time of Justinian this province was incorporated into Armenia Magna ("Greater Armenia"). In the Geography of Anania Shirakatsi, a 7th-century text, Sper is listed as being part of Bardzr Hayk ("High Armenia" or "Upper Armenia"). Hewsen speculates that "Bardzr Hayk" may simply be a translation of the Roman/Byzantine name for the province.[22] The border between Byzantine-ruled and Sasanid Persian-ruled Armenia crossed the Choruh valley somewhere between İspir and Yusufeli.[23] Sper was a Bagratid domain in the fourth to sixth centuries but at some point they lost direct control of Bayburt to the Byzantine empire, possibly soon after 387. Bayburt was refortified by the Byzantines in the period of Justinian and was eventually incorporated into its theme of Chaldia.[23] Middle AgesIn 1203, Rukn ad-din Suleiman II of Rum decided to capture the southern shores of the Black Sea and rule over Asia minor. He invaded the Kingdom of Georgia with 400 000 Muslim warriors from the emirates and sultanates of Erzinca, Abulistan, Erzerum and Sham (Syria) and took control over several southern Georgian provinces including Speri. In the same year, by winning in the Battle of Basiani, Georgia managed to banish the Turks and liberate the region of Speri again.

In the 15th century Sper was controlled by the Ak Koyunlu confederation. In 1502, after the defeat and collapse of the confederation, its territory passed into the hands of Safavid Persia;[23] however, localised Ak Koyunlu rule continued in Sper until, taking advantage of the dissolution of the Ak Koyunlu state following the death of Yakub, it was taken by Mzechabuk, the Atabeg of Samtskhe. The name of Mzechabuk's lieutenant in charge of Ispir during all or part of this period is known thanks to a colophon added in 1512 to an Armenian manuscript that tells of the "principality over Sper of Baron Kitevan, from the Georgian nation". Mzechabuk pursued a policy of appeasement with the Ottoman Empire and surrendered Ispir fortress to Sultan Selim in October 1514.[24] The Ottoman Empire had taken all of Sper from Mzechabuk probably by 1515.[23] Early modern historyIn 1520 Sper became a kaza within the Ottoman Empire; in 1536 speri became a sanjak.[24] The Ispir valley was still almost completely Armenian Christian in the early 16th century: the Ottoman census recorded no Muslims.[23] Muslims would increase in later centuries and eventually become the majority.[citation needed] In 1548, during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), the towns of Ispir and Bayburt were taken and destroyed by the Safavid Shah Tahmasp.[24] During World War I, in 1916 the region was taken by Russians forces and retaken by the newly formed Turkish Republic in 1918. NotesReferences

|

||||||||