|

Snooker

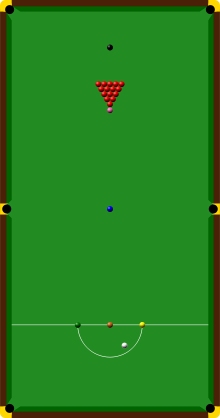

Snooker (pronounced UK: /ˈsnuːkər/ SNOO-kər, US: /ˈsnʊkər/ SNUUK-ər)[1][2] is a cue sport played on a rectangular billiards table covered with a green cloth called baize, with six pockets: one at each corner and one in the middle of each long side. First played by British Army officers stationed in India in the second half of the 19th century, the game is played with 22 balls, comprising a white cue ball, 15 red balls and 6 other balls—a yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black—collectively called 'the colours'. Using a snooker cue, the individual players or teams take turns to strike the cue ball to pot other balls in a predefined sequence, accumulating points for each successful pot and for each foul committed by the opposing player or team. An individual frame of snooker is won by the player who has scored the most points, and a snooker match ends when a player wins a predetermined number of frames. In 1875, army officer Neville Chamberlain, stationed in India, devised a set of rules that combined black pool and pyramids. The word snooker was a well-established derogatory term used to describe inexperienced or first-year military personnel. In the early 20th century, snooker was predominantly played in the United Kingdom, where it was considered a "gentleman's sport" until the early 1960s before growing in popularity as a national pastime and eventually spreading overseas. The standard rules of the game were first established in 1919 when the Billiards Association and Control Club was formed. As a professional sport, snooker is now governed by the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association. The World Snooker Championship first took place in 1927, and Joe Davis—a key figure and pioneer in the early growth of the sport—won fifteen successive world championships between 1927 and 1946. The "modern era" of snooker began in 1969 after the broadcaster BBC commissioned the television series Pot Black, later airing daily coverage of the World Championship which was first televised in 1978. The most prominent players of the modern era are Ray Reardon (1970s), Steve Davis (1980s) and Stephen Hendry (1990s), each winning at least six world titles. Since 2000, Ronnie O'Sullivan has won the World Championship seven times, most recently in 2022. Top professional players compete in regular tournaments around the world, earning millions of pounds on the World Snooker Tour—a circuit of international events featuring competitors of many different nationalities. The World Championship, the UK Championship and the Masters together make up the Triple Crown Series and are considered by many players to be the most highly valued titles. The main professional tour is open to both male and female players, and there is a separate women's tour organised by World Women's Snooker. Competitive snooker is also available to non-professional players, including seniors and people with disabilities. The popularity of snooker has led to the creation of many variations based on the standard game but with different rules or equipment, including six-red snooker, the short-lived "snooker plus" and the more recent Snooker Shoot Out version. HistorySnooker originated in the second half of the 19th century in India during the British Raj.[3] In the 1870s, billiards was popular among British Army officers stationed in Jubbulpore, India, and several variations of the game were devised during this time.[3][4] A similar game, which originated at the Officers' Mess of the 11th Devonshire Regiment in 1875,[5][6] combined the rules of two pool games: pyramids, played with 15 red balls positioned in a triangle,[a][8][9][10] and black pool, which involved potting designated balls.[11][12][13] Snooker was further developed in 1882 when its first set of rules was finalised by British Army officer Neville Chamberlain,[b][5][14] who helped devise and popularise the game at Stone House in Ootacamund on a table built by Burroughes & Watts that had been sent to India by sea.[15][16] At the time, the word snooker was a slang term used in the British Army to describe new recruits and inexperienced military personnel; Chamberlain used the word to deride the inferior performance of a young fellow officer at the table.[14][17][18] The new game of snooker featured in an 1887 issue of the Sporting Life newspaper in England, which led to a growth in popularity.[5] Chamberlain was revealed to be the inventor, 63 years after the fact, in a letter to The Field magazine published on 19 March 1938.[5] Snooker became increasingly popular across the Indian colonies of the British Raj and in the United Kingdom, but it remained a game played mostly by military officers and the gentry.[19] Many gentlemen's clubs with a snooker table would refuse entry to non-members who wished to go in and play snooker;[5][c] to cater for the growing interest, smaller and more open snooker clubs were formed.[5] The Billiards Association (formed in 1885) and the Billiards Control Club (formed in 1908) merged to form the Billiards Association and Control Club (BA&CC) and a new, standardised set of rules for snooker was first established in 1919.[22][23] The possibility of a drawn game was abolished by the use of a re-spotted black as a tiebreaker.[22] These early rules are similar to those used in the modern game, although rules for a minimal point penalty were imposed later.[24]  Played in 1926 and 1927, the first World Snooker Championship—then known as the Professional Championship of Snooker—was won by Joe Davis.[3][25][26] The Women's Professional Snooker Championship (now the World Women's Snooker Championship) was created in 1934 for top female players.[27][28] Davis, himself a professional English billiards and snooker player, raised the game from a recreational pastime to a professional sporting activity.[29][30] He retired from the world championships in 1946, having won all fifteen tournaments held up to that date.[31][32] Snooker declined in popularity in the post-war era; the 1952 World Snooker Championship was contested by only two players and was replaced by the World Professional Match-play Championship, which was also discontinued in 1957.[25][6] In an effort to boost the game's popularity, Davis introduced a variation known as "snooker plus" in 1959, with the addition of two extra colours, but this version of the game was short-lived.[33] A world championship for top amateur players, now known as the IBSF World Snooker Championship, was founded in 1963,[34] and the official world championship was revived on a challenge basis in 1964.[35] At the end of 1968, the World Snooker Championship reverted to a knockout tournament format, with eight competitors; the tournament concluded in 1969 with John Spencer winning the title.[36][37] The BBC had first launched its colour television service in July 1967;[38] in 1969, David Attenborough, then the controller of BBC2, commissioned the snooker tournament television series Pot Black primarily to showcase the potential of the BBC's new colour television service—the green table and multi-coloured balls provided an ideal opportunity to demonstrate the advantages of the new broadcasting technology.[6][39][40] The series became a ratings success and was, for a time, the second-most popular show on BBC2 after Morecambe and Wise.[41] Due to these developments, the year 1969 is taken to mark the beginning of snooker's modern era.[42] The World Snooker Championship moved in 1977 to the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, where it has been staged ever since,[43] and the 1978 World Snooker Championship was the first to receive daily television coverage.[44] Snooker quickly became a mainstream sport in the United Kingdom,[45][46] Ireland, and much of the Commonwealth, and has remained consistently popular since the late 1970s, with most of the major tournaments being televised.[11] In 1985, an estimated 18.5 million viewers stayed up until the early hours of the morning to watch the conclusion of the World Championship final between Dennis Taylor and Steve Davis, a record viewership in the UK for any broadcast on BBC Two and for any broadcast after midnight.[47][48] As professional snooker grew as a mainstream sport, it became heavily dependent on tobacco advertising. Cigarette brand Embassy sponsored the World Snooker Championship for thirty consecutive years from 1976 to 2005, one of the longest-running deals in British sports sponsorship.[49] In the early 2000s, a ban on tobacco advertising led to a reduction in the number of professional tournaments,[50][51] which decreased from twenty-two events in 1999 to fifteen in 2003.[52][53] The sport had become more popular in Asia with the emergence of players such as Ding Junhui and Marco Fu,[54][55] and still received significant television coverage in the UK—the BBC dedicated 400 hours to snooker in 2007, compared to just 14 minutes 40 years earlier.[56] However, the British public's interest in snooker had waned significantly by the late 2000s. Warning that the sport was "lurching into terminal crisis", The Guardian newspaper predicted in 2010 that snooker would cease to exist as a professional sport within ten years.[57] In the same year, promoter Barry Hearn gained a controlling interest in the World Snooker Tour, pledging to revitalise the "moribund" professional game.[58][59][60] Over the following decade, the number of professional tournaments increased, with 44 events held in the 2019–20 season.[61] Snooker tournaments were adapted to make them more suitable for television audiences, with some tournaments being played over a shortened duration,[62] or the Snooker Shoot Out, which is a timed, one-frame competition.[63] The prize money for professional events increased, with the top players earning several million pounds over the course of their careers.[64] During the COVID-19 pandemic, the professional tour was confined to events played within the United Kingdom and Ireland. In the 2022–23 season, only two professional ranking tournaments were played outside the UK, the European Masters in Fürth and the German Masters in Berlin, while lucrative Chinese events remained off the calendar.[65] Snooker referees are an integral part of the sport, and some have become well-known personalities in their own right. Len Ganley, John Street and John Williams officiated at seventeen of the first twenty World Snooker finals held at the Crucible Theatre.[66] Since 2000, non-British and female referees have become more prominent in the sport; Dutch referee Jan Verhaas became the first non-Briton to referee a World Championship final in 2003,[67] while Michaela Tabb became the first woman to do so in 2009.[68] Tabb was the only woman refereeing on the professional tour when she joined it in 2002,[69][70] but tournaments now routinely feature female referees such as Desislava Bozhilova,[71] Maike Kesseler,[72] and Tatiana Woollaston.[73] GameplayEquipment   A standard full-size snooker table measures 12 ft × 6 ft (365.8 cm × 182.9 cm), with a rectangular playing surface measuring 11 ft 8.5 in × 5 ft 10.0 in (356.9 cm × 177.8 cm).[74] The playing surface is surrounded by small cushions along each side of the table. The height of the table from the floor to the top of the cushions is 2 ft 10.0 in (86.4 cm).[75] The table has six pockets: one at each corner and one at the centre of each of the two longer side cushions.[75] One drawback of using a full-size table is the amount of space required to accommodate it, which limits the locations where the game can easily be played. The minimum room size that allows space on all sides for comfortable cueing is 22 ft × 16 ft (6.7 m × 4.9 m).[76] While pool tables are common to many pubs, snooker tends to be played either in private settings or in public snooker halls.[77] The game can also be played on smaller tables,[74] with variant table sizes including 10 ft × 5 ft (305 cm × 152 cm), 9 ft × 4.5 ft (274 cm × 137 cm), 8 ft × 4 ft (244 cm × 122 cm), and 6 ft × 3 ft (183 cm × 91 cm).[78] The cloth on a snooker table is usually a form of tightly woven woollen green baize,[79] with a directional nap that runs lengthwise from the baulk end of the table to the far end near the black ball spot.[80] The nap affects the speed and trajectory of the balls, depending on the direction of the shot and whether any side spin is placed on the ball.[80][81] Even if the cue ball is struck in precisely the same manner, the effect of the nap will differ according to whether the ball is directed towards the baulk line or towards the opposite end of the table.[5][80][81] A snooker ball set consists of 22 unmarked balls: 15 reds, 6 coloured balls, and 1 white cue ball. The colours are one each of yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black,[74] although the brown and blue balls were not a part of the original rules.[17] Each ball has a diameter of 2+1⁄16 inches (52.5 mm).[75] At the start of the game, the red balls are racked into a tightly packed equilateral triangle, and the colours are positioned at designated spots on the table. The cue ball is placed inside the "D" ready for the break-off shot.[75] Each player has a snooker cue (or simply a "cue"), not less than 3 ft (91.4 cm) in length, which is used to strike the cue ball. The tip of the cue must only make contact with the cue ball and is never used for striking any of the reds or colours directly.[75] Snooker accessories include: chalk for the tip of the cue, to help apply spin on the cue ball; various different rests such as the swan or spider, for playing shots that are difficult to play by hand; extensions for lengthening the cue; a triangle for racking the reds; and a scoreboard, typically attached to a wall near the snooker table.[82] A traditional snooker scoreboard resembles an abacus and records the points scored by each player for the current frame in units and twenties, as well as the frame scores. A simple scoring bead is sometimes used, called a "scoring string" or "scoring wire".[83] Each segment of the string (bead) represents one point as the players can move one or several beads along the string.[83] Additional accessories include cue tips of varying hardness to suit player preferences, anti-slip cue grips for better control, and specialized table brushes and cloths to maintain optimal table conditions. Rules ObjectiveA player wins a frame by scoring more points than their opponent. At the start of a frame, the object balls are positioned on the table as shown in illustration A. Starting with the cue ball in the "D", the first player executes a break-off shot by striking the cue ball with the tip of their cue, aiming to hit any of the red balls in the triangular pack. The players then take alternating turns at playing shots,[d] with the aim of potting a red ball into a pocket and thereby scoring one point. Failure to make contact with a red ball constitutes a foul, which results in penalty points being awarded to the opponent.[75] At the end of each shot, the cue ball remains in the position where it has come to rest, unless it has entered a pocket (from where it is returned to the "D"), ready for the next shot.[75] If the cue ball finishes in contact with an object ball, a touching ball is called;[e] the player must then play away from that ball without moving it, otherwise the player will concede penalty points.[75]: 21 When a red ball has entered a pocket, the striker[f] must then choose a coloured ball (or "colour") and attempt to pot it.[g] If successful, the value of the potted colour is added to the player's score, and the colour is returned to its designated spot on the table.[h] The player must then pot another red ball followed by another colour. The process of alternately potting reds and colours continues until the striker fails to pot the desired object ball or commits a foul—at which point the opponent comes to the table to start the next turn—or when there are no red balls remaining in play.[75] Points accumulated by potting successive object balls are called a "break" (see Scoring below).[75] At the start of each player's turn, the objective is to first pot a red ball, unless all reds are off the table or the player has been awarded a free ball, which allows them to nominate another object ball in place of a red.[84] The cue ball can contact an object ball directly or it may be made to bounce off one or more cushions before hitting the required object ball.[75] The game continues until all 15 red balls have been potted and only the 6 colours and the cue ball are left on the table.[75] The colours must next be potted in the ascending order of their values, from lowest to highest, i.e. yellow first (worth 2 points), then green (3 points), brown (4 points), blue (5 points), pink (6 points), and finally black (7 points); at this stage of the game, each colour remains in the pocket after being potted.[75] When the final ball is potted, the player who has accumulated the most points wins the frame.[75][i] If there are not enough points remaining on the table for a player to potentially win the frame, that player may offer to concede the frame while at the table (but not while their opponent is still at the table); a frame concession is a common occurrence in professional snooker.[75][84] However, players will often play on even when there are not enough points available for them to win, in the hope of laying one or more "snookers" to force their opponent into playing foul shots.[75][84] Snookers are shots designed to make it difficult for the opponent to play a legal shot on their next turn, such as leaving another ball between the cue ball and the object ball.[85] If the scores are equal when all object balls have been potted, the black is used as a tiebreaker in a situation called a "re-spotted black". The black ball is returned to its designated spot and the cue ball is played in-hand, meaning that it may be placed anywhere on or within the lines of the "D" to start the tiebreak. The player to take the first strike in the tiebreak is chosen at random, and the game continues until one of the players either wins the frame by potting the black ball or loses the frame by committing a foul.[75]: 20 Professional and competitive amateur matches are officiated by a referee who is charged with ensuring the proper conduct of players and making decisions "in the interests of fair play". The responsibilities of the referee include announcing the points scored during a break, determining when a foul has been committed and awarding penalty points and free balls accordingly, replacing colours onto their designated spots after being potted, restoring the balls to their previous positions after the "miss" rule has been invoked (see Scoring below), and cleaning the cue ball or any object ball upon request by the striker.[75]: 39 Another duty of the referee is to recognise and declare a stalemate when neither player is able to make any progress in the frame. If both players agree, the balls are returned to their starting positions (known as a "re-rack") and the frame is restarted, with the same player taking the break-off shot as in the abandoned frame.[75]: 33 Professional players usually play the game in a sporting manner, declaring fouls they have committed that the referee has not noticed,[86] acknowledging good shots from their opponent, and holding up a hand to apologise for a fortunate shot (known as a "fluke").[86][87] Scoring

Points in snooker are gained from potting the object balls in the correct sequence. The total number of consecutive points (excluding fouls) that a player amasses during one visit to the table is known as a "break".[74] For example, a player could achieve a break of 15 by first potting a red followed by a black, then another red followed by a pink, before failing to pot the next red. A break of 100 points or more is referred to as a century break; these are recorded over the career of a professional player.[88] A maximum break in snooker (often known as a "147" or a "maximum") is achieved by potting all reds with blacks, then potting all six colours in sequence, yielding 147 points.[89] As of 18 January 2025,[update] there have been 210 officially confirmed maximum breaks achieved in professional competition.[90] Penalty points are awarded to a player when their opponent commits a foul. This can occur for various reasons, such as sending the cue ball into a pocket or failing to hit the object ball. The latter is a common foul committed when a player fails to escape from a "snooker", where the previous player has left the cue ball positioned such that no legal ball can be struck directly in a straight line without being wholly or partially obstructed by an illegal ball. Fouls incur a minimum of four penalty points unless a higher-value object ball is involved in the foul,[j] up to a maximum of seven penalty points where the black ball is concerned.[75]: 26–28 [k] When a foul is committed, the offending player's turn ends and the referee announces the penalty. All points scored in the break before the foul occurred are awarded to the striker, but no points are scored for any ball pocketed during the foul shot.[75] If dissatisfied with the position left after a foul, the next player may nominate the opponent who committed the foul to continue playing from where the balls have come to rest. If the referee has also called a "miss"—meaning that the offending player is deemed not to have made their best possible attempt to hit the object ball—the next player has the option of having the balls replaced to their original positions and forcing their opponent to replay the intended shot. If, after a foul, it is not possible to cleanly strike both sides of the object ball directly, the referee may call a free ball, allowing the next player to nominate any other ball in place of the object ball they might normally have played.[75] If a player is awarded a free ball with all fifteen reds still in play, they can potentially make a break exceeding 147, with the highest possible being a 155 break, achieved by nominating the free ball as an extra red, then potting the black as the additional colour after potting the free-ball red, followed by the fifteen reds with blacks, and finally the colours.[91] Jamie Cope was the first player to achieve a verified 155 break during a practice frame in 2005.[92]  One game of snooker is called a "frame", and a snooker match generally consists of a predetermined number of frames. Most matches in current professional tournaments are played as the best of 7, 9, or 11 frames, with finals usually the best of 17 or 19 frames. The World Championship uses a longer format, with matches ranging from the best of 19 frames in the first round to best of 35 for the final, which is played over four sessions of play held over two days.[93] Some early world finals had much longer matches, such as the 1947 World Snooker Championship, which was played over the best of 145 frames.[94][95] Governance and tournamentsProfessionalWorld Snooker TourProfessional snooker players compete on the World Snooker Tour, which is a circuit of world ranking tournaments and invitational events held throughout the snooker season. All competitions are open to professional players who have qualified for the tour, and selected amateur players, but most events include a separate qualification stage. Players can qualify for the tour by virtue of their position in the world rankings from prior seasons, by winning continental championships, or through the Challenge Tour or Q School events.[96] Players on the World Snooker Tour generally gain a two-year "tour card" for participation in the events.[96] Beginning in the 2014–15 season, some players have also received invitational tour cards in recognition of their outstanding contributions to the sport; these cards are issued at the discretion of the World Snooker Board, and have been awarded to players including Steve Davis, James Wattana, Jimmy White, and Stephen Hendry.[97] Some additional secondary tours have been contested over the years. A two-tier structure was adopted for the 1997–98 snooker season; comprising six tournaments known as the WPBSA Minor Tour was open to all professionals, but only ran for one season.[98][99] A similar secondary UK Tour was first played from the 1997–98 season, which was renamed the Challenge Tour in 2000, Players Tour Championship in 2010 and returned as the Challenge Tour in 2018.[100][99][101] The global governing body for professional snooker is the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA),[102][103] founded in 1968 as the Professional Billiards Players' Association.[104][105] The WPBSA owns and publishes the official rules of snooker,[103][106] and has overall responsibility for policy-making in the professional sport of snooker.[104] World Snooker Ltd is responsible for the professional tour which is owned by both the WPBSA and Matchroom Sport.[107] World rankingsEvery player on the World Snooker Tour is assigned a position on the WPBSA's official world ranking list, which is used to determine the seedings and the level of qualification each player requires for the tournaments on the professional circuit.[108] The current world rankings are determined using a two-year rolling points system, where points are allocated to the players according to the prize money earned at designated tournaments.[109] This "rolling" list is maintained and updated throughout the season, with points from tournaments played in the current season replacing points earned from the corresponding tournaments of two seasons ago. Additionally, "one-year" and "two-year" ranking lists are compiled at the end of every season, after the World Championship; these year-end lists are used for pre-qualification at certain tournaments and for tour-card guarantees.[108] The top 16 players in the world ranking list, generally regarded as the "elite" of the professional snooker circuit,[110] are not required to pre-qualify for some of the tournaments, such as the Shanghai Masters, the Masters and the World Snooker Championship.[111] Certain other events, such as those in the Players Series, use the one-year ranking list to qualify; these use the results of the current season to denote participants.[112] There are approximately 128 places available on the World Snooker Tour each season.[113] As of the 2024–25 season, players in the top 64 on the official ranking list are guaranteed a tour place for the next season, as well as a maximum of 31 players who are currently on the first year of a two-year tour card, and the top four prize money earners during the most recent season who are not already qualified; this being assessed after the World Championship.[114]  TournamentsThe oldest current professional snooker tournament is the World Snooker Championship,[93] which has taken place as an annual event most years since 1927.[115][116] Hosted at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield since 1977,[115] the championship was sponsored by tobacco company Embassy from 1976 to 2005[50] and has since been sponsored by various betting companies after the introduction of an EU-wide ban on the advertising of tobacco products.[117][118][119] The World Championship is the most highly valued title in professional snooker,[120] in terms of financial reward (the tournament has carried a £500,000 winner's prize since 2019), ranking points and prestige.[121][122] The UK Championship, held annually since 1977, is considered to be the second most important ranking tournament after the World Championship.[123] These two events, and the annual non-ranking Masters tournament, make up snooker's Triple Crown Series;[124][125] among the oldest competitions on the professional circuit, the Triple Crown events are valued by many players as the most prestigious.[125] As of April 2024[update], only eleven players have won all three events,[126] the most recent being Judd Trump who completed the Triple Crown in May 2019.[127] The Triple Crown events are televised in the UK by the BBC,[128][129][130] while most other tournaments are broadcast across Europe on the Eurosport network,[131] or ITV Sport,[132] as well as numerous other broadcasters internationally.[133][134] After facing some criticism for matches taking too long,[135] Matchroom Sport chairman Barry Hearn introduced a series of timed tournaments: the shot-timed Premier League Snooker, held between 1987 and 2012, featured seven players invited to compete at regular United Kingdom venues and was televised on Sky Sports.[122] The players had twenty-five seconds to take each shot, with each player allowed five time-outs per match. The format did achieve some success but was not afforded the same amount of press attention or status as the regular ranking tournaments.[135] The event was removed from the professional tour after the 2012–13 season, when the Champion of Champions was re-established;[136] players qualify for this tournament by virtue of winning other events in the season, with sixteen champions competing.[137][l] Classified as a "precision sport" by the International Olympic Committee, snooker has never been contested at the Summer Olympics.[138][139][m] In 2015, the WPBSA submitted a bid for snooker to be included at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics,[141] but without success.[142] Since its launch in October 2017, the World Snooker Federation (WSF) has been advocating for snooker to be added to the Olympic and Paralympic programme.[143][144] Their initial bid for the 2024 Paris Olympics was unsuccessful,[145][146] but the WSF is campaigning for snooker to be included at the 2032 Brisbane Olympics.[138] Olympic status would create a significant public funding opportunity for the sport and boost its global exposure.[138] A trial of the format for cue sports to be played at the 2024 Games was conducted at the 2019 World Team Trophy, which also featured nine-ball and carom billiards.[147] Snooker has been contested at the World Games since 2001 and was included as an event at the 2019 African Games.[148][149][150] CriticismSeveral players, including Ronnie O'Sullivan, Mark Allen and Steve Davis, have claimed that there are too many tournaments in the season, causing burnout of players.[151] O'Sullivan played only a subset of tournaments in 2012, so he could spend more time with his children; as a result he ended the 2012–13 season ranked 19th in the world despite being the world champion. O'Sullivan played only one tournament in 2013, the World Championship, which he won.[152] He suggested that a "breakaway tour" with fewer events would be beneficial to the sport, but none was organised.[153] Some players, including 2005 world champion Shaun Murphy, have asserted that a 128-player professional tour is financially unsustainable.[154][155] Lower-ranked professional players can struggle to make a living from the sport, especially after paying tournament entry fees, travel costs and other expenses.[156] In 2023, Stephen Maguire criticised the World Snooker Tour and WPBSA, claiming that "the game is dying right in front of our eyes",[157] and stating that some players ranked within the world's top 30 were seeking jobs outside the sport due to lack of earning potential from tournaments.[158] AmateurNon-professional snooker (including youth competition) is governed by the International Billiards and Snooker Federation (IBSF).[159] The highest level competition in the amateur sport is the IBSF World Snooker Championship.[160] Events held specifically for seniors are handled by the WPBSA under the World Seniors Tour,[161][162][163] the highest level of the senior sport being the World Seniors Championship.[163] World Disability Billiards and Snooker (WDBS) is a WPBSA subsidiary that organises events and playing aids in snooker and other cue sports for people with disabilities.[77] The most prestigious amateur event in England is the English Amateur Championship; first held in 1916, this is the oldest snooker competition still being played in the world.[164] Snooker is a mixed gender sport that affords men and women the same opportunities to progress at all levels of the game. While the main professional tour is open to male and female players alike, there is also a separate women's tour organised by World Women's Snooker (formerly the World Ladies Billiards and Snooker Association) which encourages female players to participate in the sport and take part in high-level amateur competitions.[77][165] The leading tournament on the women's tour is the World Women's Snooker Championship, the winner of which receives a two-year tour card to the main professional tour.[166] Reanne Evans won the women's world title a record twelve times, including ten consecutive victories from 2005 to 2014.[167][168] She has also participated on the World Snooker Tour and has taken part in the qualifying rounds of the main World Snooker Championship on five occasions, reaching the second round in 2017.[169] Evans holds the record for the highest break made in WWS competition, having achieved a 140 break twice (in 2008 and 2010).[28] Other successful female players are Kelly Fisher (with five women's world titles), Ng On-yee (with three), and most recently Nutcharut Wongharuthai, Siripaporn Nuanthakhamjan and Bai Yulu, who won the World Women's Snooker Championship in 2022, 2023 and 2024 respectively.[168] Some leagues have allowed clubs to exclude female players from tournaments.[170][171] A committee member of the Keighley league defended allowing such teams in the league as necessity: "If we lose two of these clubs [with the men-only policies] we would lose four teams and we can't afford to lose four teams otherwise we would have no league."[170] A World Women's Snooker spokesperson commented, "It is disappointing and unacceptable that in 2019 that [sic] players such as Rebecca Kenna have been the victim of antiquated discriminatory practices."[172] The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Snooker said, "The group believes that being prevented from playing in a club because of gender is archaic."[172] Important playersJoe Davis, founder of the World Snooker Championship, won 15 consecutive world titles between 1927 and 1946.[173] Steve Davis won the World Championship six times in the 1980s.[174] Stephen Hendry won the World Championship seven times in the 1990s.[175] Ronnie O'Sullivan has won seven world titles in the 21st century.[176] After the creation of the World Snooker Championship, snooker overtook billiards as the most popular cue sport in the United Kingdom.[177] Joe Davis was the World Champion for twenty years, retiring unbeaten in the event after claiming his fifteenth world title in 1946 when the tournament was reinstated after the Second World War.[173] During his entire professional career, Davis remained undefeated when playing on equal terms, although he did lose some matches in handicapped tournaments.[173][178][179] He was only ever beaten on level terms by his younger brother Fred Davis, but not until after he had retired from professional play.[173] By 1947, Fred Davis was deemed by his older brother ready to become World Champion,[173] but he lost that year's world final to Walter Donaldson.[180][181] Davis and Donaldson contested the next four world finals, with Davis winning three of the four.[182] With the abandonment of the World Championship in 1953 (after the boycott of the 1952 event by British professionals), the World Professional Match-play Championship became the unofficial world championship.[183] Fred Davis won the tournament every year from 1952 to 1956 but did not enter the 1957 event.[175] John Pulman won in 1957 and was the most successful player of the 1960s, winning the world title seven times between April 1964 and March 1968 while the World Championship was being contested at irregular intervals on a challenge basis.[95][175] Pulman's winning streak ended when the tournament reverted to a knockout format in 1968.[184][185] Ray Reardon was the dominant force of the 1970s, winning six world titles (in 1970, 1973–1976, and 1978), and John Spencer won the world title three times (in 1969, 1971 and 1977).[186][187] Steve Davis (no relation to Joe or Fred) won his first World Championship in 1981, becoming the 11th World Snooker Champion since 1927.[188][189] He won six world titles altogether (in 1981, 1983, 1984 and 1987–1989) and competed in the most-watched snooker match, the 1985 World Snooker Championship final, which he lost to Dennis Taylor.[47] Stephen Hendry became the 14th World Snooker Champion in 1990, aged 21 years and 106 days, the youngest player ever to have lifted the world title.[6] He dominated the sport through the 1990s,[190] winning the World Championship seven times (in 1990, 1992–1996, and 1999).[175][191] Ronnie O'Sullivan has claimed the most world titles since 2000, having won the World Championship seven times (in 2001, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2013, 2020 and 2022).[176] John Higgins and Mark Selby have both won four world titles (Higgins in 1998, 2007, 2009 and 2011; Selby in 2014, 2016, 2017 and 2021),[192][193] and Mark Williams three (in 2000, 2003 and 2018).[194][195] O'Sullivan, Higgins and Judd Trump are the only players to have made over 1,000 career century breaks.[196] O'Sullivan also holds the record for the most maximum breaks compiled in professional competition, having achieved his 15th in October 2018.[197] O'Sullivan also holds the record for the most ranking titles (41) and most Triple Crown titles (23) achieved in the sport.[198] VariantsSome versions of snooker, such as six-red or ten-red snooker, are played with almost identical rules to the standard game but with fewer object balls, reducing the time taken to play each frame.[199][200] The Six-red World Championship, contested annually in Bangkok, Thailand, was a regular fixture on the World Snooker Tour between 2012 and 2023.[201] A World Women's 10-Red Championship was held annually in Leeds, England, from 2017 to 2019.[202][203][204] Geographic variations exist in the United States and Brazil, while speed versions of the standard game have been developed in the United Kingdom. American snooker is an amateur version of the game played almost exclusively in the United States.[205] With simplified rules and generally played on smaller tables, this variant dates back to 1925.[n][205] Sinuca brasileira (or "Brazilian snooker") is a variant of snooker played exclusively in Brazil, with fully divergent rules from the standard game and using only one red ball instead of fifteen. At the start of the game, the single red is positioned halfway between the pink ball and the side cushion, and the break-off shot cannot be used to pot the red or place the opponent in a snooker.[207] The Snooker Shoot Out is a variant snooker tournament consisting of single-frame matches for an accelerated format. First staged in 1990, the idea was resurrected in 2011 with a modified version that was added to the professional tour in the 2010–11 season and upgraded to a ranking event in 2017.[208][209] Other games have been designed with an increased number of object balls in play. One example is "snooker plus", which included two additional colours: an orange ball worth eight points positioned between pink and blue, and a purple ball worth ten points positioned between brown and blue, increasing the maximum possible break to 210.[210] Introduced at the 1959 News of the World Snooker Plus Tournament, this variant failed to gain popularity and is no longer played.[211] Power Snooker was a short-lived cue sport based on aspects of snooker and pool; this was first played competitively in 2010 and again in 2011, but the format was discontinued after it failed to gain widespread appeal.[208] Using nine red balls racked in a diamond-shaped pack at the start of the game, the matches were limited to a fixed game-play period of 30 minutes.[212] Tenball was a snooker variant designed specifically for the television show of the same name, an LWT production that was broadcast for one series in 1995. An extra ball worth ten points (the yellow and black "tenball") was added between the blue and pink, and the game had a slightly revised set of rules compared to the standard game.[213] See alsoNotes

References

Bibliography

External linksLook up snooker in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||