|

Slave trade in the Mongol Empire

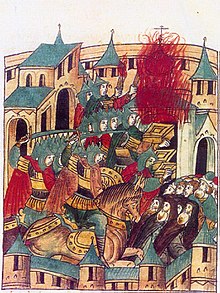

The slave trade in the Mongol Empire refers to the slave trade conducted by the Mongol Empire (1206–1368). This includes the Mongolia vassal khanates which was a part of the Mongol Empire, such as the Chagatai Khanate (1227–1347), Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Ilkhanate (1256–1335), and Golden Horde (1242–1368). In pre-imperial Mongolia, slavery had not played any big part, but the Mongol invasions and conquests of the 13th century created a great influx of war captives, which were by custom considered legitimate to enslave, and caused a significant expansion of slavery and slave trade. The Mongol Empire established a massive international slave trade founded upon war captives enslaved during the Mongol conquests, which were distributed by market demand around the empire via a network of slave markets connected through the cities of the empire. The slave trade network established through the Mongol Empire was partially built upon earlier slave markets, and partially upon new. Many centers of the slave trade survived the fall of the Mongol Empire, notably the major Bukhara slave trade, which survived until the 1870s. Background and supplyThe Mongol slave trade was based on war captives and human tributes, and the constant warfare and conquests of the Mongol Empire and their vassal khanates supplied a constant influx of enslaved people to the slave trade network of the Empire. This contributed to the constant warfare within the Mongol Empire. The Mongol warfare developed routines for the capture of slaves. When the Mongols captured a city, the routine were to enslave people deemed to be suitable for the slave market, such as craftsmen and other skilled artisans.[1] There was a system for whom were enslaved. One practice was to count the boys of a captured city and select one of ten as a prisoner, and then do the same with girls.[2] If a man had three sons, one was selected for enslavement.[2] All adult men and women who were unmarried were defined as legitimate for enslavement.[2] The established standard for war captives was to ask for ransom for war captives and, if no ransom was offered, sell them as slaves.[2] Another method to acquire slaves were taxation in the form of human tributes from conquered states. The Mongol often asked for tribute in the form of humans; this custom was not ended in conquered Russia until the Mongols introduced a regulated tribute tax in the form of silver and fur from Russia in 1257–1259.[3] Enslavement could also be used against subjugated people unable to pay their taxes or tributes. Up until the Russian Uprising of 1262, for example, the Mongols sold Russian peasants who were unable to pay tribute to the Italian slave traders in the Crimea.[4] The slave trade was fed by raids and purchase by slave traders; by tributary system in which subjugated states were forced to give slaves as tributes; and by war captives during the warfare campaigns during the Mongol Empire and its succeeding Khanates. The tradeOnce captive, the enslaved people were distributed to the different slave markets around the Empire.[2] The Mongol Empire established a massive international slave trade with war captives based on the Mongol invasions and conquests, and used a network of cities to transport slaves across different parts of the empire in accordance with market demand for particular categories of slaves; such as Christian slaves to the Muslim slave market, and Muslim slaves to the Christian world.[5] The slave trade network of the Mongol Empire was organized in a route from northern China to northern India; from northern India to the Middle East via Iran and Central Asia; and from Central Asia to Europa via the Steppe of the Kipchak territory between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea and Caucasus.[5] This slave trade route was connected via a number of cities used to transport slaves to the peripheries of the empire, consisting of the capitals of the Mongol khanates - with the capital of Qaraqorum as the main center - and already existing slave trade centers, notably the old slave trade center of Bukhara.[5] The network was new but used and included many old slave trade centers, notably the ancient Central Asian slave trade center in Bukhara.[5] The different slave trade centers were used by the empire to cater to the specific slave markets in different parts of the world, which all had different needs and a market for different categories of slaves, which together made it possible for the empire to dispose of all slaves for the highest possible profit. Slave MarketThe extensive slave trade network of the empire enabled the distribution of various categories of slaves to parts of the world where they could fetch the highest profits. The slave markets across different regions had distinct demands, necessitating a flexible approach to slave trading to maximize profit. Three main factors influenced the distribution of slaves to the most profitable markets: 1. Religious factor: To ensure maximum sale potential, it was necessary to cross religious borders, as neither Christians nor Muslims would purchase slaves of their own faith. This resulted in Christian slaves being sold to Muslims and Muslim slaves to Christians.[5] 2. Military slavery: This was a significant market, especially for male slaves in the Muslim world, providing a robust demand for military personnel.[5] 3. Ethnic or racial preferences: Different ethnicities were preferred for various roles across different regions; for instance, Turkish men were often utilized as slave soldiers in the Middle East, Tartars as household slaves in Italy, and Korean girls as concubines in China.[5] ChinaThe slave market was traditionally limited in China, were slavery did not play a big role. Since the large free Chinese peasant population were obligated to perform the hard labor work commanded by the ruling elites, there were less need for large scale slavery in China. There were nevertheless a market for skilled slaves and luxury slaves in China, in addition to the slaves owned by the government, performing task within state institutions. These were skilled artisans and craftsmen, and girls used as concubine sex slaves; there was a preference for concubines of Korean ethnicity in Mongol Yuan China.[6] The Mongols took over the state owned government slaves after the conquest of China. A large part of the slaves that did exist in China were government slaves - divided in to military, civil and government categories - which were used for a number of tasks, such as to populate state military colonies (tuntian), as agriculture laborers and in state institutions such as brew houses, and as state artisans.[7] The minority of foreign slaves sold in the Chinese slave market were primarily kipchak Turks, European Rus people and Koreans.[8] In contrast to other slave markets in the Empire, however, Chinese buyers primarily preferred Chinese slaves.[9] There were no social or religious taboo in China for selling, buying and owning people of the same ethnicity and religion.[10] There was an established custom in China to enslave criminals and rebels, [11] as well as impoverished or indebted people selling themselwes or their children in to slavery.[12] The preferred ethnicity for slaves in China were therefore Chinese. [13] There were consequently no big import of slaves to China, but Chinese were popular as slaves abroad, and the Mongols therefore maintained an export of Chinese slaves to foreign market. The Mongols exported Chinese people as slaves to Mongolia and to the Muslim world after the conquest of Jin China in 1211-1234, [14] and an active export of Chinese slaves were ongoing until the 1330s.[15] The Yuan scholar Song Zichen estimated that the slaves distributed to the ownership of the Mongol princes, dignitaries and military leaders in China constituted half of the population in Northern China after the conquest of Jin China.[16] EuropeThe Black Sea slave trade in the North West was used by the Mongol Empire to dispose of slaves deemed suitable for use in Christian Europe. The Genoese and Venetian slave trades established in the Black Sea ports in parallel with the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus' and were flooded with slaves when the Mongols used the Italian slave traders in the Black Sea ports to dispose of war captives from the Russian campaign, and the Mongols established a long-term collaboration with the Italian slave traders at the Black Sea.[17] The Mongol Empire used the European market to dispose of mainly Muslim Tartar war captives, who was taken captives during the conquests and inner warfare and rebellions of the Empire. Muslim captives were not possible to sell in the Muslim world, but could be sold to Christian Europe, and in the period of 1351 and 1408, between 80 and 90 percent of all slaves trafficked by Genoa and Venice to South Europe from the Black Sea were of Tatar ethnicity.[18] Most slaves sold by the Mongols to Europe via the Black Sea slave trade were Tatar or Mongol, though a few Chinese and Indian slaves are also noted to have been sold.[19] The slave trade to Europe mainly concerned Tatar house slaves [20] to Italy, Spain and Portugal and was a small market compared to the export to the Muslim world.[18] IndiaOne of the most important markets for the Mongol Empire were the Muslim Delhi Sultanate in northern India. The Delhi Sultanate had an import of slaves from the Central Asian slave market already before the Mongol Empire, and this trade was not interrupted when the Mongols took the Central Asian Bukhara slave market, which was merely incorporated in to the empire's slave trade network. The Delhi Sultanate was dependent on a constant supply of male Turkish slaves from Central Asia as slave soldiers, and these were regularly provided to India via the Hindu Kush from Central Asia.[20] Middle EastThe Muslim world of the Middle East was the biggest market for the slave trade of the Empire.[18] There were traditionally an established market in the Muslim world for slave girls for sexual slavery as concubines, and for slave-boys for military slavery as slave soldiers. Bukhara in Central Asia was since ancient times a provider of slaves to the Muslim Middle East, and used by the Empire to traffic slaves suitable for the Muslim slave market; from Central Asia, the slave trade route continued via Tabriz to Aleppo.[20] Male slaves for military slavery (Ghilman) were trafficked from China to the Middle East via Central Asia and Iran.[20] When the Kipchak Turks were subjugated by the Mongols after the 1237-1241 campaign, many of the Kipchak people were exported by the Mongols to slavery in Egypt.[20] Turkish slave soldiers were transported from the Golden Horde in Central Asia to the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt via the Black Sea.[20] The slave market of the Muslim world was used by the empire to depose of Christian slaves. After the Siege of Acre, the inhabitants of the city, being Frankish Christians, were deported to the slave market of Baghdad.[19] In the Ilkhanate in Iran, Mongol soldiers reportedly often owned slaves used to cultivate the land allotted to them.[21] MongoliaThe Nomadic culture in Mongolia had less use of wide scale slave labor, and slaves were kept mainly as a marginal symbol of wealth and prestige; male slaves were ruled for herding, while female slaves were more appreciated for their wide range of use as herding, domestic chores and sexual slavery as wives and concubines.[22] Slavery also increased in the domestic market of Mongolia during the expansion of the Empire. Mongolia itself therefore also became a destination of slaves. The main capital of Qaraqorum was the main base of the cities forming the slave trade network of the Empire, and the presence of slaves of all ethnicities, such as Russians or Arabs, are noted by contemporary witnesses in Mongolia. The capital of the Empire received large quantities of war prisoners for its own market. An example is the Siege of Baghdad of 1258, after which thousands of Arab people of the conquered city were taken as slaves to Azerbaijan or Mongolia.[20] Genghis Khan was among many recorded warlords who would often employ the mass, indiscriminate murder of men and boys regardless if they were soldiers, civilians, or simply in the way. In the year 1202, after he and Ong Khan allied to conquer the Tatars, he ordered the execution of every Tatar man and boy taller than a linchpin, and enslaved Tatar women for sexual purposes. This order was given as collective punishment for the fatal poisoning of Genghis Khan's father, Yesugei, for which the Mongols blamed the Tatars according to The Secret History of the Mongols.[23] AftermathThe Mongol Empire were gradually divided from 1294 until its final division in 1368. The network of slave trade cities established by the Empire continued in many cases as separate slave trades after 1368. The Ancient Bukhara slave trade, for example, continued for another five centuries until 1873. See alsoReferences

|