|

Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855)

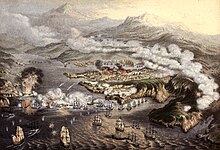

The siege of Sevastopol (at the time called in English the siege of Sebastopol) lasted from October 1854 until September 1855, during the Crimean War. The allies (French, Sardinian, Ottoman, and British) landed at Eupatoria on 14 September 1854, intending to make a triumphal march to Sevastopol, the capital of the Crimea, with 50,000 men. Major battles along the way were Alma (September 1854), Balaklava (October 1854), Inkerman (November 1854), Tchernaya (August 1855), Redan (September 1855), and, finally, Malakoff (September 1855). During the siege, the allied navy undertook six bombardments of the capital, on 17 October 1854; and on 9 April, 6 June, 17 June, 17 August, and 5 September 1855. The siege of Sevastopol is one of the last classic sieges in history.[10] The city of Sevastopol was the home of the tsar's Black Sea Fleet, which threatened the Mediterranean. The Russian field army withdrew before the allies could encircle it. The siege was the culminating struggle for the strategic Russian port in 1854–55 and was the final episode in the Crimean War. During the Victorian Era, these battles were repeatedly memorialized. The siege of Sevastopol was the subject of Crimean soldier Leo Tolstoy's Sebastopol Sketches and the subject of the first Russian feature film, Defence of Sevastopol. The Boulevard de Sébastopol, a major artery in Paris, was named for the victory in the 1850s, while the Battle of Balaklava was made famous by Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem "The Charge of the Light Brigade" and Robert Gibb's painting The Thin Red Line. A panorama of the siege itself was painted by Franz Roubaud. DescriptionSeptember 1854The allies (French, Ottoman, and British) landed at Eupatoria on 14 September 1854.[11] The Battle of the Alma (20 September 1854), which is usually considered the first battle of the Crimean War (1853–1856), took place just south of the River Alma in the Crimea. An Anglo-French force under Jacques Leroy de Saint Arnaud and FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan defeated General Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov's Russian army, which lost around 6,000 troops.[12] Moving from their base at Balaklava at the start of October, French and British engineers began to direct the building of siege lines along the Chersonese uplands to the south of Sevastopol. The troops prepared redoubts, gun batteries, and trenches.[13] With the Russian army and its commander Prince Menshikov gone, the defence of Sevastopol was led by Vice Admirals Vladimir Alexeyevich Kornilov and Pavel Nakhimov, assisted by Menshikov's chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Eduard Totleben.[14] The military forces available to defend the city were 4,500 militia, 2,700 gunners, 4,400 marines, 18,500 naval seamen, and 5,000 workmen, totalling just over 35,000 men.[citation needed] The naval defense of Sevastopol included 8 artillery batteries: 3 on the north shore (Konstantin Battery or Fort Constantine, Mikhail battery or Fort Michael, battery no. 4) and 5 on the northern shore (Pavel battery or Fort Pavel, battery no. 8, Alexander battery or Fort Alexander, battery no. 8). The Russians began by scuttling their ships to protect the harbour, then used their naval cannon as additional artillery and the ships' crews as marines.[15] Those ships deliberately sunk by the end of 1855 included Grand Duke Constantine, City of Paris (both with 120 guns), Khrabryi, Imperatritsa Maria, Chesma, Rostislav, and Yagondeid (all 84 guns), Kavarna (60 guns), Konlephy (54 guns), steam frigate Vladimir, steamboats Thunderer, Bessarabia, Danube, Odessa, Elbrose, and Krein.[citation needed] October 1854By mid-October, the Allies had some 120 guns ready to fire on Sevastopol; the Russians had about three times as many.[16] On 5 October (old style date, 17 October new style)[a] the artillery battle began.[16] The Russian artillery first destroyed a French magazine, silencing their guns. British fire then set off the magazine in the Malakoff redoubt, killing Admiral Kornilov, silencing most of the Russian guns there, and leaving a gap in the city's defences. However, the British and French withheld their planned infantry attack, and a possible opportunity for an early end to the siege was missed.[citation needed] At the same time, to support the Allied land forces, the Allied fleet pounded the Russian defences and shore batteries. Six screw-driven ships of the line and 21 wooden sail were involved in the sea bombardment (11 British, 14 French, and two Ottoman Turkish). After a bombardment that lasted over six hours, the Allied fleet inflicted little damage on the Russian defences and coastal artillery batteries while suffering 340 casualties among the fleet. Two of the British warships were so badly damaged that they were towed to the arsenal in Constantinople for repairs and remained out of action for the remainder of the siege, while most of the other warships also suffered serious damage due to many direct hits from the Russian coastal artillery. The bombardment resumed the following day, but the Russians had worked through the night and repaired the damage. This pattern would be repeated throughout the siege.[citation needed] November 1854In late October and early November, the battles of Balaclava[17] and Inkerman[18] took place beyond the siege lines. Balaclava gave the Russians a morale boost and convinced them that the Allied lines were thinly spread out and undermanned.[11] But after their defeat at Inkerman,[19] the Russians saw that the siege of Sevastopol would not be lifted by a battle in the field, so instead they moved troops into the city to aid the defenders. Toward the end of November, a winter storm ruined the Allies' camps and supply lines. Men and horses sickened and starved in the poor conditions.[20] While Totleben extended the fortifications around the Redan bastion and the Malakoff redoubt, British chief engineer John Fox Burgoyne sought to take the Malakoff, which he saw as the key to Sevastopol. Siege works were begun to bring the Allied troops nearer to the Malakoff; in response, Totleben dug rifle pits from which Russian troops could snipe at the besiegers. In a foretaste of the trench warfare that became the hallmark of the First World War, the trenches became the focus of Allied assaults.[21] 1855 The Allies were able to restore many supply routes when winter ended. The new Grand Crimean Central Railway, built by the contractors Thomas Brassey and Samuel Morton Peto, which had been completed at the end of March 1855[22] was now in use bringing supplies from Balaclava to the siege lines. The 24-mile long railroad delivered more than five hundred guns and plentiful ammunition.[22] The Allies resumed their bombardment on 8 April (Easter Sunday). On 28 June (10 July), Admiral Nakhimov died from a head wound inflicted by an Allied sniper.[23] On 24 August (5 September) the Allies started their sixth and the most severe bombardment of the fortress. Three hundred and seven cannon fired 150,000 rounds, with the Russians suffering 2,000 to 3,000 casualties daily. On 27 August (8 September), thirteen Allied divisions and one Allied brigade (total strength 60,000) began the last assault. The British assault on the Great Redan failed, but the French, under General MacMahon, managed to seize the Malakoff redoubt and the Little Redan, making the Russian defensive position untenable. By the morning of 28 August (9 September), the Russian forces had abandoned the southern side of Sevastopol.[9][24] Although defended heroically and at the cost of heavy Allied casualties, the fall of Sevastopol would lead to the Russian defeat in the Crimean War.[1] Most of the Russian casualties were buried in Brotherhood Cemetery in over 400 collective graves. The three main commanders (Nakhimov, Kornilov, and Istomin) were interred in the purpose-built Admirals' Burial Vault.[citation needed] Battles during the siege

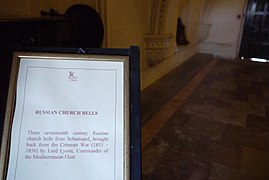

Fate of Sevastopol cannon The British sent cannons seized at Sevastopol to many towns in Britain, and several important cities across the Empire.[b][27][28] Additionally, several were sent to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. These cannon are now all kept at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (renamed after the closing of RMA Woolwich shortly after the Second World War) and are displayed in front of Old College, next to cannon from Waterloo and other battles. Many of the cannon sent to towns in Britain were melted down during the Second World War to help the war effort, though several of these have subsequently been replaced by replicas.[c][29] The cascabel (the large ball at the rear of old muzzle-loaded guns) of several cannon captured during the siege was said to have been used to make the British Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the British Armed Forces. However, Hancocks, the manufacturer, confirms that the metal is Chinese, not Russian, bronze. The cannons used are in the Firepower Museum in Woolwich and are clearly Chinese. There would be no reason why Chinese cannon would be in Sevastopol in the 1850s and it is likely that the VC guns were, in fact, British trophies from the China war in the 1840s held in the Woolwich repository. Though it had been suggested that the VCs should be made from Sevastopol cannons, it seems that in practice, they were not. Testing of medals which proved not to be of Russian bronze has given rise to stories that some Victoria Crosses were made of low grade material at certain times but this is not so – all Victoria Crosses have been made from the same metal from the start. Components of the 1861 Guards Crimean War Memorial by John Bell, in Waterloo Place, St James's, London, were made from melted down Sevastopol cannons.[30] Sevastopol BellsFollowing the end of the siege, two large bells were taken by British forces as war trophies from the Church of the Twelve Apostles.[31] Along with two smaller bells, they were appropriated and transported by Lieutenant Colonel John St George, who commanded the Royal Artillery siege train.[32] They were displayed at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, before the larger one was taken to Aldershot Garrison, where it was mounted on a wooden frame on Gun Hill. In 1879, it was moved to the bell tower of the Cambridge Military Hospital, the garrison's medical facility. It was moved in 1978 to the officer's mess in Hospital Road and more recently to St Omer Barracks; it is a Grade II listed structure. The second bell was taken to Windsor Castle and installed in the Round Tower; by tradition it is only rung on the death of a king or queen.[31] Gallery

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![A view of the "Valley of the Shadow of Death" near Sevastopol, taken by Roger Fenton in March 1855. It was so named by soldiers because of the number of cannonballs that landed there, falling short of their target, during the siege.[33]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Roger_Fenton_-_Shadow_of_the_Valley_of_Death.jpg/237px-Roger_Fenton_-_Shadow_of_the_Valley_of_Death.jpg)