|

Serial port

A serial port is a serial communication interface through which information transfers in or out sequentially one bit at a time.[1] This is in contrast to a parallel port, which communicates multiple bits simultaneously in parallel. Throughout most of the history of personal computers, data has been transferred through serial ports to devices such as modems, terminals, various peripherals, and directly between computers. While interfaces such as Ethernet, FireWire, and USB also send data as a serial stream, the term serial port usually denotes hardware compliant with RS-232 or a related standard, such as RS-485 or RS-422. Modern consumer personal computers (PCs) have largely replaced serial ports with higher-speed standards, primarily USB. However, serial ports are still frequently used in applications demanding simple, low-speed interfaces, such as industrial automation systems, scientific instruments, point of sale systems and some industrial and consumer products. Server computers may use a serial port as a control console for diagnostics, while networking hardware (such as routers and switches) commonly use serial console ports for configuration, diagnostics, and emergency maintenance access. To interface with these and other devices, USB-to-serial converters can quickly and easily add a serial port to a modern PC. Hardware

Modern devices use an integrated circuit called a UART to implement a serial port. This IC converts characters to and from asynchronous serial form, implementing the timing and framing of data specified by the serial protocol in hardware. The IBM PC implements its serial ports, when present, with one or more UARTs. Very low-cost systems, such as some early home computers, would instead use the CPU to send the data through an output pin, using the bit banging technique. These early home computers often had proprietary serial ports with pinouts and voltage levels incompatible with RS-232. Before large-scale integration (LSI) made UARTs common, serial ports were commonly used in mainframes and minicomputers, which would have multiple small-scale integrated circuits to implement shift registers, logic gates, counters, and all the other logic needed. As PCs evolved serial ports were included in the Super I/O chip and then in the chipset.

DTE and DCEThe individual signals on a serial port are unidirectional and when connecting two devices, the outputs of one device must be connected to the inputs of the other. Devices are divided into two categories: data terminal equipment (DTE) and data circuit-terminating equipment (DCE). A line that is an output on a DTE device is an input on a DCE device and vice versa, so a DCE device can be connected to a DTE device with a straight wired cable, in which each pin on one end goes to the same numbered pin on the other end. Conventionally, computers and terminals are DTE, while peripherals such as modems are DCE. If it is necessary to connect two DTE (or DCE) devices together, a cable with reversed TX and RX lines, known as a cross-over, roll-over or null modem cable must be used. GenderGenerally, serial port connectors are gendered, only allowing connectors to mate with a connector of the opposite gender. With D-subminiature connectors, the male connectors have protruding pins and female connectors have corresponding round sockets.[2] Either type of connector can be mounted on equipment or a panel; or terminate a cable. Connectors mounted on DTE are likely to be male, and those mounted on DCE are likely to be female (with the cable connectors being the opposite). However, this is far from universal; for instance, most serial printers have a female DB25 connector, but they are DTEs.[3] In this circumstance, the appropriately gendered connectors on the cable or a gender changer can be used to correct the mismatch. ConnectorsThe only connector specified in the original RS-232 standard was the 25-pin D-subminiature, however, many other connectors have been used to save money or save on physical space, among other reasons. In particular, since many devices do not use all of the 20 signals that are defined by the standard, connectors with fewer pins are often used. While specific examples follow, countless other connectors have been used for RS-232 connections. The 9-pin DE-9 connector has been used by most IBM-compatible PCs since the Serial/Parallel Adapter option for the PC-AT, where the 9-pin connector allowed a serial and parallel port to fit on the same card.[4] This connector has been standardized for RS-232 as TIA-574. Some miniaturized electronics, particularly graphing calculators[5] and hand-held amateur and two-way radio equipment,[6] have serial ports using a phone connector, usually the smaller 2.5 or 3.5 mm connectors and the most basic 3-wire interface—transmit, receive and ground.  8P8C connectors are also used in many devices. The EIA/TIA-561 standard defines a pinout using this connector, while the rollover cable (or Yost standard) is commonly used on Unix computers and network devices, such as equipment from Cisco Systems.[7]  Many models of Macintosh favor the related RS-422 standard, mostly using circular mini-DIN connectors. The Macintosh included a standard set of two ports for connection to a printer and a modem, but some PowerBook laptops had only one combined port to save space.[8] 10P10C connectors can be found on some devices.[9] Another common connector is a 10 × 2 pin header common on motherboards and add-in cards which is usually converted via a ribbon cable to the more standard 9-pin DE-9 connector (and frequently mounted on a free slot plate or other part of the housing).[10] PinoutsThe following table lists commonly used RS-232 signals and pin assignments:[11]

Signal Ground is a common return for the other connections; it appears on two pins in the Yost standard but is the same signal. The DB-25 connector includes a second Protective Ground on pin 1, which is intended to be connected by each device to its own frame ground or similar. Connecting Protective Ground to Signal Ground is a common practice but not recommended. Note that EIA/TIA 561 combines DSR and RI,[13][14] and the Yost standard combines DSR and DCD. Hardware abstractionOperating systems usually create symbolic names for the serial ports of a computer, rather than requiring programs to refer to them by hardware address. Unix-like operating systems usually label the serial port devices /dev/tty*. TTY is a common trademark-free abbreviation for teletype, a device commonly attached to early computers' serial ports, and * represents a string identifying the specific port; the syntax of that string depends on the operating system and the device. On Linux, 8250/16550 UART hardware serial ports are named /dev/ttyS*, USB adapters appear as /dev/ttyUSB* and various types of virtual serial ports do not necessarily have names starting with tty. The DOS and Windows environments refer to serial ports as COM ports: COM1, COM2,..etc.[15] Common applications for serial portsThis list includes some of the more common devices that are connected to the serial port on a PC. Some of these such as modems and serial mice are falling into disuse while others are readily available. Serial ports are very common on most types of microcontroller, where they can be used to communicate with a PC or other serial devices.

Since the control signals for a serial port can be driven by any digital signal, some applications used the control lines of a serial port to monitor external devices, without exchanging serial data. A common commercial application of this principle was for some models of uninterruptible power supply which used the control lines to signal loss of power, low battery, and other status information. At least some Morse code training software used a code key connected to the serial port to simulate actual code use; the status bits of the serial port could be sampled very rapidly and at predictable times, making it possible for the software to decipher Morse code. Serial computer mice may draw their operating power from the received data or control signals.[16][17] Settings

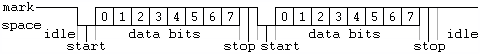

Serial standards provide for many different operating speeds as well as adjustments to the protocol to account for different operating conditions. The most well-known options are speed, number of data bits per character, parity, and number of stop bits per character. In modern serial ports using a UART integrated circuit, all these settings can be software-controlled. Hardware from the 1980s and earlier may require setting switches or jumpers on a circuit board. The configuration for serial ports designed to be connected to a PC has become a de facto standard, usually stated as 9600/8-N-1. SpeedSerial ports use two-level (binary) signaling, so the data rate in bits per second is equal to the symbol rate in baud. The total speed includes bits for framing (stop bits, parity, etc.) and so the effective data rate is lower than the bit transmission rate. For example, with 8-N-1 character framing, only 80% of the bits are available for data; for every eight bits of data, two more framing bits are sent. A standard series of rates is based on multiples of the rates for electromechanical teleprinters; some serial ports allow many arbitrary rates to be selected, but the speeds on both sides of the connection must match for data to be received correctly. Bit rates commonly supported include 75, 110, 300, 1200, 2400, 4800, 9600, 19200, 38400, 57600 and 115200 bit/s.[19] Many of these standard modem baud rates are multiples of either 1.2 kbps (e.g., 19200, 38400, 76800) or 0.9 kbps (e.g., 57600, 115200).[23] Crystal oscillators with a frequency of 1.843200 MHz are sold specifically for this purpose. This is 16 times the fastest bit rate, and the serial port circuit can easily divide this down to lower frequencies as required. The capability to set a bit rate does not imply that a working connection will result. Not all bit rates are possible with all serial ports. Some special-purpose protocols such as MIDI for musical instrument control, use serial data rates other than the teleprinter standards. Some serial port implementations can automatically choose a bit rate by observing what a connected device is sending and synchronizing to it. Data bitsThe number of data bits in each character can be 5 (for Baudot code), 6 (rarely used), 7 (for true ASCII), 8 (for most kinds of data, as this size matches the size of a byte), or 9 (rarely used). 8 data bits are almost universally used in newer applications. 5 or 7 bits generally only make sense with older equipment such as teleprinters. Most serial communications designs send the data bits within each byte least significant bit first. Also possible, but rarely used, is most significant bit first; this was used, for example, by the IBM 2741 printing terminal. The order of bits is not usually configurable within the serial port interface but is defined by the host system. To communicate with systems that require a different bit ordering than the local default, local software can re-order the bits within each byte just before sending and just after receiving. ParityParity is a method of detecting errors in transmission. When parity is used with a serial port, an extra data bit is sent with each data character, arranged so that the number of 1 bits in each character, including the parity bit, is always odd or always even. If a byte is received with the wrong number of 1s, then it must have been corrupted. Correct parity does not necessarily indicate absence of corruption as a corrupted transmission with an even number of errors will pass the parity check. A single parity bit does not allow implementation of error correction on each character, and communication protocols working over serial data links will typically have higher-level mechanisms to ensure data validity and request retransmission of data that has been incorrectly received. The parity bit in each character can be set to one of the following:

Aside from uncommon applications that use the last bit (usually the 9th) for some form of addressing or special signaling, mark or space parity is uncommon, as it adds no error detection information. Odd parity is more useful than even parity since it ensures that at least one state transition occurs in each character, which makes it more reliable at detecting errors like those that could be caused by serial port speed mismatches. The most common parity setting, however, is none, with error detection handled by a communication protocol. To allow detection of messages damaged by line noise, electromechanical teleprinters were arranged to print a special character when received data contained a parity error. Stop bitsStop bits sent at the end of every character allow the receiving signal hardware to detect the end of a character and to resynchronize with the character stream. Electronic devices usually use one stop bit. If slow electromechanical teleprinters are used, one-and-one-half or two stop bits may be required. Conventional notation The data/parity/stop (D/P/S) conventional notation specifies the framing of a serial connection. The most common configuration for the personal computing devices is 8-N-1 (also spelled as 8N1, 8-None-1[24]), in which there is one start bit, eight ("8") data bits, no ("N") parity bit, and one ("1") stop bit.[25] In this notation, the parity bit is not included into the count of the data bits. For example, 7/E/1 (7E1) means that an even parity bit is added to the 7 data bits for a total of 8 bits between the start and stop bits. The abbreviation is usually given together with the line speed in bits per second, as in "9600–8-N-1". The speed (or baud rate) includes bits for framing (stop bits, parity, etc.), thus the effective data rate is lower than the baud rate. For 8-N-1 encoding, only 80% of the bits are available for data (for every eight bits of data, ten bits are sent over the serial link — one start bit, the eight data bits, and the one stop bit).[24] Flow controlFlow control is used in circumstances where a transmitter might be able to send data faster than the receiver is able to process it. To cope with this, serial lines often incorporate a handshaking method. There are hardware and software handshaking methods. Hardware handshaking is done with extra signals, often the RS-232 RTS/CTS or DTR/DSR signal circuits. RTS and CTS are used to control data flow, signaling, for instance, when a buffer is almost full. Per the RS-232 standard and its successors, DTR and DSR are used to signal that equipment is present and powered up so are usually asserted at all times. However, non-standard implementations exist, for example, printers that use DTR as flow control. Software handshaking is done for example with ASCII control characters XON/XOFF to control the flow of data. The XON and XOFF characters are sent by the receiver to the sender to control when the sender will send data, that is, these characters go in the opposite direction to the data being sent. The system starts in the sending allowed state. When the receiver's buffers approach capacity, the receiver sends the XOFF character to tell the sender to stop sending data. Later, after the receiver has emptied its buffers, it sends an XON character to tell the sender to resume transmission. It is an example of in-band signaling, where control information is sent over the same channel as its data. The advantage of hardware handshaking is that it can be extremely fast, it works independently of imposed meaning such as ASCII on the transferred data and it is stateless. Its disadvantage is that it requires more hardware and cabling, and both ends of the connection must support the hardware handshaking protocol used. The advantage of software handshaking is that it can be done with absent or incompatible hardware handshaking circuits and cabling. The disadvantage, common to all in-band control signaling, is that it introduces complexities in ensuring that control messages get through even when data messages are blocked, and data can never be mistaken for control signals. The former is normally dealt with by the operating system or device driver; the latter normally by ensuring that control codes are escaped (such as in the Kermit protocol) or omitted by design (such as in ANSI terminal control). If no handshaking is employed, an overrun receiver might simply fail to receive data from the transmitter. Approaches for preventing this include reducing the speed of the connection so that the receiver can always keep up, increasing the size of buffers so it can keep up averaged over a longer time, using delays after time-consuming operations (e.g. in termcap) or employing a mechanism to resend data which has not been received correctly (e.g. TCP). See also

References

Further reading

External linksWikibooks has a book on the topic of: Programming:Serial Data Communications

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||