|

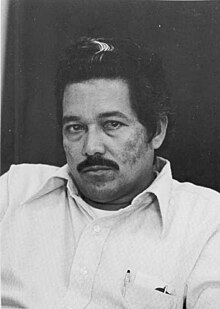

Separatism in the Faichuk Islands The separatist movement in the Faichuk Islands is a political movement calling for autonomy and independence for the Faichuk Islands located in the state of Chuuk, in the Federated States of Micronesia, a federal country also made up of the states of Kosrae, Pohnpei and Yap. Although the Faichuk Islands' separatism emerged in 1959, it did not take on political importance until 1979, and played a major role in national politics until 1983. In 1979, in a referendum, the inhabitants expressed their desire for autonomy through the creation of a state separate from that of Chuuk. In 1980, the Chuuk Legislative Assembly endorsed this move. The following year, after several unsuccessful attempts, a bill to create a Faichuk state was passed by the Congress of the Federated States of Micronesia, but the President of the Federated States of Micronesia, Tosiwo Nakayama, vetoed it in the name of national unity. In 1983, the separatists successfully called on the islanders of the Faichuk Islands to boycott the vote on the Treaty of Free Association with the United States. From then until 2001 the political current calling for autonomy remained barely audible. On that date, a Faichuk constitution explicitly declaring independence was passed by plebiscite, and a unilateral declaration of independence was transmitted to Leo Falcam, President of the Federated States of Micronesia. The leaders of the Faichuk Islands attempted to establish lasting contacts with the United States, with the aim of seeking independence. This goal was soon suspended, however, and several bills for autonomous statehood were unsuccessfully presented to Congress throughout the 2000s. In 2011 two political attempts were made to force their way in. A self-proclaimed Faichuk ambassador appeared before the Chinese ambassador to the Federated States of Micronesia, and an influential separatist leader claimed to be acting president of the Republic of Faichuk. From 2012 onwards, demands appeared to shift from independence for the Faichuk Islands region to independence for the entire state of Chuuk. Long-standing demandsIn 1944 the Carolines Islands came under the control of the United States, which administered them as a Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands under a UN mandate received in 1947.[1] A desire for sovereignty and autonomy had been claimed with varying intensity since 1959[2] by the Faichuk Islands, i.e. the islands and atolls of Paata, Polle, Tol, Wonei, Eot, Fala-Beguets, Romanum and Udot (an area covering 73 km²).[2][3] Its origins lie in traditional rivalries between clans and chiefs in the Chuuk Lagoon.[4] The reasons were also economic. The islanders criticized the leaders of the district of Chuuk, the future state of Chuuk, for paying too much attention to the capital Weno and not enough to the problems of the outlying islands, the Faichuk Islands in particular.[5] An autonomous district would benefit from more goods, services, medical treatment and facility improvement projects.[5] 1979–1981The years 1979–1981 were critical in the history of the Federated States of Micronesia, with strong territorial antagonisms that conditioned and still condition its survival.[4][6] As part of the gradual formation of the Federated States of Micronesia towards independence, the granting of statehood to Kosrae in 1977,[7] for no other reason than to ensure ratification of the future country's constitution in a referendum on July 12, 1978, reinforced the idea of autonomy.[5] The vote was widely boycotted in the Faichuk Islands, with some polling stations not even opening.[8] In 1979, a referendum showed that over 80% of the inhabitants wanted a separate state to be formed.[9][10] On June 6, 1980 the Chuuk Legislative Assembly passed a resolution urging the Congress of the Federated States of Micronesia to pass legislation granting statehood to the Faichuk Islands.[10] A bill to this effect was introduced at the first ordinary session of Congress, but was not debated.[11] A second attempt a few months later also failed.[5]  At a special session of the Congress in Weno, capital of the state of Chuuk, in July 1981, a delegation from the Faichuk Islands asked the senators to create a new state within the Federated States of Micronesia. A draft law with this objective was passed unanimously.[12] The result was a surprise, according to political scientists Austin Ranney and Howard R. Penniman.[4] President Tosiwo Nakayama, originally elected Senator from Chuuk, was faced with the dilemma between alienating a large part of his own constituency by vetoing the bill and initiating the first step in a process of fragmentation of the Federation into a multitude of tiny island entities, with regions such as the Mortlock, southeast of the Truk Islands, and the Central Carolinas between the Yap Islands and the Truk Islands, having indicated that they would claim the same status if the Faichuk became a state.[12] The aim of the leaders of the Faichuk Islands, which represented a quarter of the population of the state of Chuuk,[4] was to gain access to a significant share of the national budget, essentially divided into four equal shares allocated to each of the four states, which would guarantee funding for major projects such as hospitals, airports, power stations, water supply systems, port facilities and roads. In the state of Chuuk, most of the funds were directed to its capital, Weno.[12] In the 1980s, according to sociologist John Connel, the Federated States of Micronesia faced, to an even greater degree than other Pacific island states, acute development challenges. Their densely-populated, widely-dispersed islands, with access to extremely limited resources, struggled with the high costs of imports and exports. In addition, the small population limited industrial opportunities and market volume. Vulnerable to the vagaries of the climate, the country also depended on costly energy expenditure and expensive infrastructure construction. The result of all this was massive trade deficits. Finally, the American colonial system resulted in a value orientation towards the bulky, unproductive and inefficient urban bureaucratic system, rather than towards the private sector. For all these reasons, and others linked to a social and political environment that placed a high priority on individual freedom, the phenomenon of migration to the United States, enabled by the Compact of Free Association, was reinforced.[13] The law passed by Congress did not determine whether funding for the new state would be half of that currently received by the State of Chuuk, or one-fifth of the total budget of the Federated States of Micronesia, which would considerably reduce the level of funding for the other states.[12] The creation of a new Chuukese state would, through the voting rights of senators, definitively ensure Chuukese dominance according to the Pohnpeians, resulting in an imbalance threatening the very nature of funding allocations, local autonomy and cultural identity.[12][5][11][14] The Yapais joined the Pohnpeians at a later stage.[5] The majority of the Micronesian population was highly critical of the choice of Congress, which was seen as offloading responsibility onto the President.[12] On October 23, 1981, after extensive consultations, Tosiwo Nakayama finally refused to promulgate the law,[6][12] arguing that it was absolutely necessary to create the unity of the nation as a prerequisite for the establishment and maintenance of a genuine domestic regime.[4] He added that the district lacked the economic and political infrastructure to support a state, that the cost of bringing it up to speed quickly would be too great, and that the Constitution was ambiguous as to the procedure to be followed in creating a state.[6][12] No serious effort was made by the Congress to challenge the veto, although it had the right to do so.[4] In November 1981, the President announced that Faichuk would become "a showcase and model of economic development".[12] Despite this disavowal of his electoral base, which could have cost him his political future, Tosiwo Nakayama was re-elected Senator by the people of Faichuk, then President by his peers in May 1983 for a second term.[5][11] In 1983 the issue of the adoption of the Compact of Free Association with the United States was replaced by others, such as the prerogatives of traditional chiefs and magistrates, local favoritism in jobs and public improvements, the ambitions of local legislators for higher office, and the resentment of Faichuk Islanders at being governed by decisions made in Weno. Three days before the referendum, the separatists chose to boycott rather than participate and vote against the pact. The decision was well taken, with only 18.5% of the 6,218 voters casting ballots, demonstrating the influence of traditional Faichuk leaders.[4] In 1986 the Federated States of Micronesia became independent.[1] That same year, Senator Leo Falcam predicted that Chuukois blood would run in the streets of Pohnpei Island if the Faichuk Islands became a separate state.[15] 2001: a renewal of demands For many years, the Faichuk district's demands were not supported by any major political movement, although the issue was regularly raised.[16][17] But on November 28, 2000, a Faichuk constitution explicitly declaring independence was voted on by plebiscite, and approved by 91.1% of the 6,167 eligible voters – residents of the district and expatriates from Hawaii, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.[2][3][10] Some voters complained that they had not been given enough information about the content of the Constitution.[18] Numerous leaders, mayors, speakers and traditional chiefs signed the Faichuk Declaration of Self-Determination, unilateral declaration of independence transmitted to the President of the Federated States of Micronesia Leo Falcam.[2] The demands were rooted in the almost total absence of local infrastructure due to a lack of funding, resulting in a feeling of marginalization.[3][2][19] The Faichuk State Commission claimed that independence would bring an influx of foreign aid, for example from Japan and Australia.[19] Coconuts and other plants would be replanted on the islands, and their inhabitants would produce copra, a product in great demand, as well as other cash-generating agricultural products.[19] In August, the commission chaired by former Chuuk governor Erhart Aten invited the US armed forces to settle in the region.[20] According to this body, the creation of a new state within the Federated States of Micronesia would create more opportunities in the Faichuk district, from industry, agriculture and fishing to private sector development and services managed by the new government.[20] The situation would also be favorable for Chuukois, as Faichuk islanders who had left to work in the Chuuk lagoon would return home, providing opportunities for unemployed Chuukois.[20] If autonomy were not voted through Congress, independence would be sought.[20] After a first failure during the year, when the presentation of the law on the status of these islands was not accepted by Congress, a second attempt was made in October.[19][20] In early 2001 Tiwiter Aritos, Senator for the Faichuk District in the Congress of the Federated States of Micronesia, convinced the members of the Faichuk State Commission to suspend the implementation of the independence project until a new draft law could be presented.[2] In the course of 2001, the Faichuk State Commission sent Alan Short, chief American negotiator, a social and economic program based on the claims of the Declaration, with an infrastructure budget.[2][19] Valued at US$288 million, it included a power plant, a coastal road on each island, water and wastewater treatment facilities, an administrative complex, educational facilities, health services, an airport, a port, telecommunications networks, housing construction and the establishment of a revolving fund to finance economic activities.[2] On October 1, 2001, an interim government was formed.[9] In December the Chuuk State Legislative Assembly passed a resolution supporting the granting of autonomous status to the islanders, so that they could enjoy the same rights as all other citizens. It encouraged Leo Falcam, President of the Federated States of Micronesia, and Congress to support the will of the people of the Faichuk Islands by submitting bills and voting for statehood.[2] 2011: a political attempt to force the issueIn February 2005 a draft law was submitted to the Federal Congress.[3] Attempts were made in September 2007[10] and again in 2009.[2][21] In 2011, Senator Tiwiter Aritos' objective was still to promote autonomy as a state, not independence. However, many Faichuk leaders were actively implementing the demands of the 2000 declaration, as requests for talks had never received a response from the federal government.[2] In July, the president of the Red Dragon construction company in Guam, although not a Micronesian citizen, appeared before Zhang Weidung, China's ambassador to the Federated States of Micronesia, as ambassador for the Faichuk Islands.[2] She was denied this title by the very angry ambassador, causing confusion among the federal representatives of the Federated States of Micronesia, including President Emanuel Mori, who were in denial about the situation.[2][22] In August, the head of the Faichuk State Commission, Kachutosy Paulus, who lived in Guam, claimed to be "Acting President of the Republic of Faichuk" in an e-mail to the press. At the same time, Pohnpei Senator Dohsis Halbert, Chairman of the Congressional Ways and Means Committee, expressed surprise at the disappearance of millions of dollars earmarked by the federal government for the Faichuk Islands.[2]  In an article published in 2011 Pohnpei journalist Bill Jaynes questioned the motivations of the separatists and wondered whether they were the work of a few determined men who acted according to their desires rather than those of the locals.[2] The situation prompted caution on the part of President Emanuel Mori, who doubted the legality of the commission and questioned Kachutosy Paulus's choice of where to live.[2] A possible transformation of demandsIn 2014, according to Micronesian President Emanuel Mori, the Chuuk state political status commission (CPSC), created in 2012, was made up of former leaders of separatism in the Faichuk Islands who were now campaigning for Chuuk state independence,[23] a view shared by Vid Raatior, one of the opponents of Chuuk independence.[24] According to Emanuel Mori, these Chuuk leaders were using the idea of secession to further their own interests.[23] The members of the commission told him that he was misleading his people and suggested that he should not interfere in Chuuk affairs. A proposed referendum on Chuuk independence was postponed several times between 2015 and 2020, then abandoned.[25] See alsoReferences

|