|

Second Guangzhou Uprising

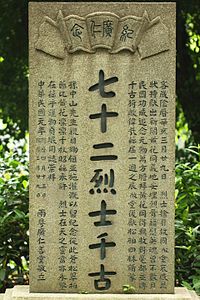

The Second Guangzhou (Canton) Uprising, known in Chinese as the Yellow Flower Mound Uprising or the Guangzhou Xinhai Uprising, was a failed uprising took place in China led by Huang Xing and his fellow revolutionaries against the Qing dynasty in Canton (Guangzhou). It is honored in Guangzhou's Yellow Flower Mound or Huanghuagang Park. History At this time Malaya, which included what is now Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore, had the largest Overseas Chinese population outside of China itself. Many of them were rich and carried out activities for the revolutionaries. On November 13, 1910, Sun Yat-sen, along with several leading figures of the Tongmenghui, gathered at the Penang conference to draw up plans for a decisive battle. The following day on November 14, 1910, Sun Yat-sen chaired an Emergency Meeting of the Tongmenghui at 120 Armenian Street (now the Sun Yat-sen Museum Penang) and raised Straits Dollars $8,000 on the spot. The planning events are known as the 1910 Penang Conference. [1] Originally planned to occur on April 13, 1911, the preparations on April 8 did not go as planned, delaying the date to April 27.[2] Huang Xing and nearly a hundred fellow revolutionaries forced their way into the residence of the Qing Viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. The uprising was initially successful but Qing reinforcements turned the battle into a catastrophic defeat. Most revolutionaries were killed, only few managed to escape. Huang Xing was wounded during the battle; he lost two of his fingers when his hand was hit by a bullet.[3] 86 bodies were found (but only 72 could be identified), and the bodies of yet many others were not found.[2][4] The dead were mostly nationalistic, revolutionary youths with all kinds of social backgrounds – former students, teachers, journalists, and patriotic overseas Chinese. Some of them were of high rank in the Alliance. Before the battle, most of the revolutionaries knew that the battle would probably be lost, since they were heavily outnumbered, but they went into battle anyway. The mission was carried out like that of a suicide squad.[2] Their letters to their loved ones were later found. LegacyThe dead were buried together in one grave on the Yellow Flower Mound, a mound near where they fought and died which has lent its name to the uprising.[2] After the Chinese revolution, a cemetery was built on the mound with the names of those 72 revolutionary nationalists. They were commemorated as the "72 martyrs."[2] Some historians believe that the uprising was a direct cause of the Wuchang uprising, which eventually led to the Xinhai Revolution and the founding of the Republic of China. Among the martyrs who sacrificed themselves was revolutionary Lin Chueh-min.[5] MemorialsThe uprising is remembered annually in Taiwan on March 29, as Youth Day.[6] The bodies of the 72 insurgents were collected by Pan Dawei and buried in a mound in the eastern suburbs of Guangzhou.[7] It was not until 1916 that it was decided to build a formal cemetery, namely Yellow Flower Mound Park. After that, the successive governments of the Republic of China continued to repair it when they were in mainland China. The government of the People's Republic of China also maintained it in the early days after the establishment of the PRC. It was destroyed by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Guangzhou Government also repaired the damaged facilities and inscriptions.[8] Members of the Kuomintang would also go to pay homage when they visited mainland China.[9]

In popular cultureThe 1980 film Magnificent 72 and the 2011 film 72 Heroes focus on the uprising. Events of the uprising open the 2011 film 1911. See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Second Guangzhou Uprising. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||