|

Schistosoma bovis

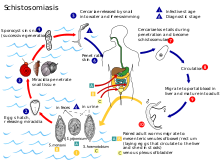

Schistosoma bovis is a two-host blood fluke, that causes intestinal schistosomiasis in ruminants in North Africa, Mediterranean Europe and the Middle East. S. bovis is mostly transmitted by Bulinus freshwater snail species. It is one of nine haematobium group species and exists in the same geographical areas as Schistosoma haematobium, with which it can hybridise. S. bovis-haematobium hybrids can infect humans, and have been reported in Senegal since 2009, and a 2013 outbreak in Corsica. Taxonomy and identificationSchistosoma bovis is a digenetic, two-host blood fluke. It was discovered by Italian parasitologist Prospero Sonsino at Zagazig meat market in Egypt in 1876 from a bull.[1] It is generally similar to other schistosomes, but Sonsino knew that it was larger and its eggs were different from those of the human species (first and only known schistosome at the time), Schistosoma haematobium, discovered by a German physician Theodor Bilharz in 1852,[2][3] then known as Bilharzia haematobium or Distomum haematobium. Sonsino gave the name Bilharzia bovis[4] following the genus classification introduced by another German physician Heinrich Meckel von Hemsbach in 1856 for the species described by Bilharz.[5][6] The eggs of S. bovis are not only larger than those of other schistosomes, but also have thicker spine with an elongated shape in the form a spindle.[7][8] The eggs are therefore the best and simplest identification key from other species.[9][10] Sonsino later revised the name as Bilharzia crassa in 1877, and then as Gynaecophorus crassa in 1992. Though the genus name remained confusing, Louis-Joseph Alcide Railliet (in 1893) and Raphaël Blanchard (in 1895) revived and maintained the species name, bovis.[4] The valid genus name Schistosoma was accepted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) in 1954,[11] following the name created by David Friedrich Weinland in 1858.[12] Thus, the original Bilharzia bovis became Schistosoma bovis.[4] Hybrids between S. bovis and the human schistosome, Schistosoma haematobium were first described in 2009 in Northern Senegalese children, and to a lesser degree hybrids between S. bovis and cattle schistosome S. curassoni found only in cattle.[13] S. bovis-haematobium hybrids were also found during the 2013 outbreak traced to the Cavu river on Corsica.[14] As a hybrid increases the host range of the parent species, they affect transmission, and as is known from other schistosome hybrid pairings, morbidity and drug susceptibility, so they are epidemiologically important.[13] Life cycle Schistosoma bovis infects two hosts, namely ruminants (cattle, goats, sheep, horses and camels) and freshwater snails (Bulinus sp. and Planorbarius sp.).[15]: 392 Experimental infections have been proven in Planorbarius metidjensis snails, which are native to Northwestern Africa and the Iberian peninsula.[citation needed] In water, its free swimming infective larval cercariae can burrow into the skin of its definite host, the ruminant, upon contact. The cercariae enter the host's blood stream, and travel to the liver to mature into adult flukes. Adult flukes can coat themselves with host antigen thus avoiding detection by the host immune system. After a period of about three weeks the young flukes migrate to the mesenteric veins of the gut to copulate. The female fluke lays eggs, which migrate into the lumen of the gut and leave the host upon defecation. In fresh water, the eggs hatch, forming free swimming miracidia.[16][17][18] Miracidia penetrate into the intermediate host, the freshwater snails[19] of the Bulinus spp., (e.g. B. globosus, B. forskalii, B. nyassanus and B. truncatus), except in Spain,[15]: 20 Portugal and Morocco, where Planorbarius metidjensis can transmit.[20] Inside the snail, the miracidium sheds its epithelium, and develops into a mother sporocyst. After two weeks the mother begins forming daughter sporocysts. One month – or more with cooler ambient temperatures – after a miracidium has penetrated into the snail, hundreds to thousands of cercariae of the same sex begin to be released through special areas of the sporocyst wall.[15]: 30 The cercariae cycle from the top of the water to the bottom in search of a host. They can enter the host epithelium within minutes.[21][15]: 34 Geographical distributionS. bovis infects snails in Africa north of the equator, Europe (Sardinia, Corsica, Spain) and the Middle East as far as Iraq.[15]: 20 S. bovis-haematobium hybrids have been reported first in Senegal in the early 1990s,[22] and then an outbreak in 2013 in Corsica.[23] DiagnosisLaboratoryThe diagnosis of schistosomiasis can be made by microscopically examining the feces for the egg. The S. bovis egg is terminally spiked, spindle shaped, and the largest in size compared to other Schistosoma eggs at 202 μm length and 72μm width.[15]: 396 In chronic infections, or if eggs are difficult to find, an intradermal injection of Schistosome antigen to form a wheal can determine infection. Alternatively diagnosis can be made by complement fixation tests.[19] As of 2012[update] commercial serological tests have included ELISA and an indirect immunofluorescence test, hampered by a low sensitivity ranging from 21% to 71%.[24] Exposure to any Schistosoma eggs or cercariae can cause false positive serological test results for individual Schistosoma species, unless highly specific antigens are used.[15]: 402 Various polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays to differentiate S. bovis from other schistosomes in urine and naturally infected snails for surveillance purposes have been described since 2010.[25] PathologyThe ova are initially deposited in the muscularis propria of the gut which leads to ulceration of the overlaying tissue. Infections are characterized by pronounced acute inflammation, blood and reactive epithelial changes. Granulomas and multinucleated giant cells may be seen.[citation needed] ImmunopathologyThe immune system responds to eggs in the liver causing hypersensitivity; an immune response is necessary to prevent damage to hepatocytes. The hosts' antibodies bind to the tegument of the schistosome but not for long since the tegument is shed every few hours. The schistosome can also take on host proteins. Schistomiasis can be divided into three phases; Within the haematobium group S. bovis and S. curassoni appear to be closely related: (1) the migratory phase lasting from penetration to maturity, (2) the acute phase which occurs when the schistosomes begin producing eggs, and (3) the chronic phase which occurs mainly in endemic areas.[19] Gene expressionS. bovis is one of the few non-bacterial species with a known moonlighting protein. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD) is also a common MP in bacteria.[26] TreatmentHistorically, antimonials and trichlorphon were tested against visceral schistosome infection in cattle.[27]: 245–248, 265–273 Antimony affects phosphofructokinase activity in Schistosoma, hycanthone intercalates Schistosoma DNA and the organophosphorus metabolite dichlorvos inhibits acetylcholinesterase, "but progressively less so in S. bovis".[15]: 44 Since the 1980s the drug of choice is praziquantel, a quinolone derivative which disrupts membranes, leading to calcium influx. It clears eggs from stool, and affects adult but not immature worms.[15]: 44–45 Damaged and dying flukes can be trapped in the liver and cause fatal portal vein thrombosis.[27] Disease preventionThe main cause of schistosomiasis is the dumping of human and animal waste into water supplies. Hygienic disposal of waste would be sufficient to eliminate the disease.[19] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||