|

Scalloped antbird

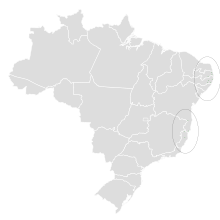

The scalloped antbird (Myrmoderus ruficauda) is an Endangered species of passerine bird in subfamily Thamnophilinae of family Thamnophilidae, the "typical antbirds". It is endemic to Brazil.[1][2] Taxonomy and systematicsThe scalloped antbird was formerly included in the genus Myrmeciza. A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2013 found that Myrmeciza, as then defined, was polyphyletic.[3] In the resulting rearrangement to create monotypic genera, four species including the scalloped antbird were moved to the resurrected genus Myrmoderus.[2] The scalloped antbird has two subspecies, the nominate M. r. ruficauda (Wied-Neuwied, 1831) and M. r. soror (Pinto, 1940).[2] DescriptionThe scalloped antbird is 14 to 15 cm (5.5 to 5.9 in) long. Adult males of the nominate subspecies have a black crown, nape, and upper back with white edges on the rearmost feathers. Their lower back is black with ochraceous-white feather edges, a rufous rump, and a white patch between their scapulars. Their tail is rufous-brown. Their flight feathers are brown with rufous edges. Their wing coverts are black with light buff tips. Their face and throat are black. Their breast and side feather are black with wide white edges and the rest of their underparts are ochre-brown. Adult females are similar to males but with browner upperparts, a pale buff and brownish gray face, a white throat with faint gray scalloping, and a pale buff breast with black scalloping. Subspecies M. r. soror is larger and paler than the nominate.[4][5] Distribution and habitatThe scalloped antbird has a disjunct distribution in southeastern Brazil. The nominate subspecies is found in southeastern Bahia, extreme eastern Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo. Subspecies M. r. soror is found further north between Paraíba and Alagoas. The species primarily inhabits semie-humid and humid evergreen forest and mature secondary woodland. Both subspecies are essentially terrestrial, and both favor areas with vine tangles and other dense understorey vegetation. M. r. soror tends to be in moister landscapes than the nominate. In elevation the species mostly occurs below 650 m (2,100 ft) but is found up to 950 m (3,100 ft).[4][5] BehaviorMovementThe scalloped antbird is a year-round resident throughout its range.[4] FeedingThe scalloped antbird's diet has not been detailed but is known to include insects and other arthropods. Individuals, pairs, and family groups forage almost entirely on the ground. They usually hop on the ground or onto low branches, capturing most prey by tossing aside or probing leaf litter. They also glean from low-hanging leaves by reaching and jumping. They do not join mixed-species feeding flocks and do not attend army ant swarms.[4][5] BreedingThe nominate subspecies of the scalloped antbird probably breeds between October and December. The breeding season of M. r. soror appears to extend to April. The species' nest is a cup made from dead leaves with a lining of thin plant fibers, placed on the ground or slightly above it in a tangle of vegetation. The clutch is two eggs that are white and heavily marked with brownish red lines. The incubation period is about 15 days and fledging occurs 12 to 14 days after hatch. Both parents incubate the eggs and provision nestlings.[4] VocalizationThe scalloped antbird's song is a "very high, sharp. almost level, rattling trill".[5] Its call is a short, buzzy "squit".[4] StatusThe IUCN originally in 1988 assessed the scalloped antbird as Threatened, then in 1994 as Vulnerable, and since 2000 as Endangered. It has a very small and fragmented range and its estimated population of between 600 and 1700 mature individuals is believed to be decreasing. "In the north-east, logging and clearance for sugarcane and pasturelands has reduced remaining forests to isolated and fragmented patches...further south, little forest remains because of conversion to plantation agriculture."[1] The species does occur in several protected areas both private and governmental, though most of them are small and may hold only a single pair. "Continued protection of existing reserves, including more vigilant protection of the Murici Ecological Reserve (being eroded at its margins by fire, and still subjected to illegal timber removal in Jan 2000) is critical to the continued survival of this species."[4] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||