|

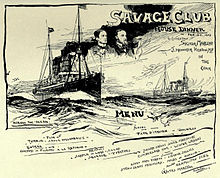

Savage Club

The Savage Club, founded in 1857, is a gentlemen's club in London, named after the poet, Richard Savage. Despite this, the club's logo is of an American Indian in a feathered headdress. Members are drawn from the fields of art, drama, law, literature, music or science. History The founding meeting of the Savage Club took place on 12 October 1857, at the Crown Tavern, Vinegar Yard, Drury Lane, after a letter by pro tempore honorary secretary George Augustus Sala was sent to prospective members.[2] The letter advised it would be 'a meeting of gentlemen connected with literature and the fine arts, and warmly interested in the promotion of Christian knowledge, and the sale of exciseable liquors' with a view to 'forming a social society or club'.[2] The inaugural gathering would also decide upon the new association's 'suitable designation'.[2]  Around 20 attended the first meeting including William Brough, Robert Brough, Leicester Silk Buckingham, John Deffett Francis, Gustav von Franck, Bill Hale, Sala, Dr G. L. Strauss and William Bernhardt Tegetmeier.[3] Andrew Halliday, joint honorary secretary in 1858, and later club president, wrote in his 1867 anthology, of how the 'suitable designation' was determined:[4]

Many of the original members were drawn from the ranks of bohemian journalists and writers for The Illustrated London News who considered themselves unlikely to be accepted into the older, arts related Garrick Club, but, within two decades, the Savage Club itself had become 'almost respectable'.[5] The early requirement – 'a working man in literature or art' – was soon broadened to include musicians, and the club's first piano was hired in 1871, prompting Halliday to tell another member 'Hang your piano... it's ruining the Club'.[6] An associated Masonic lodge was established in 1887. The club has hosted a variety of guests over the years including American writer and humorist Mark Twain,[7] and the Australian cricket team during its 1934 English tour.[8] In the aftermath of World War II, Oswald Mosley, founder of the British Union of Fascists, arrived as a guest of Henry Williamson, author of Tarka the Otter, but was asked to leave.[9] The club features in Arthur Conan Doyle's classic novel, The Lost World.[10] The club moved from its original home at the Crown Tavern, the next year to the Nell Gwynne Tavern. In 1863 it moved to Gordon's Hotel in Covent Garden, then to 6–7 Adelphi Terrace, later to 9 Fitzmaurice Place, Berkeley Square, London W1, and, from 1936 to the end of 1963, Carlton House Terrace in St James's (previously the home of the Conservative statesman Lord Curzon).[11] In 1990, the club moved to a room within the National Liberal Club at 1 Whitehall Place, London SW1. In 2020 it was issued with a year's notice by the General Committee of the National Liberal Club as part of a negotiation around its future occupancy. A source at the National Liberal Club commented: "The red line for us is whether one of our members, of any sex, could use the Savage Club's bar whenever it is opened."[12] Members of the National Liberal Club (or indeed of any other non-reciprocal Club) would however not be allowed to use the Savage Club's facilities unless invited as guests, as is the case with any private Members' club, and the Savage Club does admit ladies as guests to the whole of its premises. The club todayIn 1962, the club had around 1,000 members,[11] at present, there are over 300[citation needed]. It remains one of the small number of London clubs that does not admit women as members, although women are admitted as guests. The club maintains a tradition of regular dinners for members and their guests, always followed by entertainment, often featuring distinguished musical performers from the club's membership.[13] Several times a year members invite ladies to share both the dinner and the entertainment, and on these occasions guests always include widows of former Savages, who are known as Rosemaries (after rosemary, a symbol of remembrance).  There are also monthly lunches, which are followed by a talk given by a member or an invited guest on a subject of which he has specific expert knowledge. MembershipMembers are classified into one of six categories which best describes their main interest: art, drama, law, literature, music or science.[1][13] They must be proposed and seconded by two existing members, and if unknown by any other members, are required to attend a club function in order to meet some members. The category of membership might mirror a member's profession, though there are many members with an interest in one or more of the membership categories, but who practise none professionally. There is a range of membership fees depending on membership category. During the weekend, members are permitted to use the East India Club in St James's Square and the Oxford and Cambridge Club in Pall Mall. There are also reciprocal arrangements with other clubs internationally.[1] Members of the Savage Club may also use accommodation at the Savile, Farmers and Lansdowne Clubs. Notable members

The Savage Club Masonic Lodge  On 11 February 1882, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), attended a dinner in his honour at the Savage Club, before becoming a member.[31] The Prince suggested a Masonic lodge, associated with the club, should be formed.[32] The Savage Club Lodge, No. 2190 received its Warrant of Constitution on 18 December 1886,[33] and was consecrated on 18 January 1887,[34] with war correspondent Sir John Richard Sommers Vine as the first Master.[35] The first treasurer was the actor Sir Henry Irving, followed by the actor Edward O'Connor Terry in 1888.[23] This tendency towards the arts continued to be reflected in the Lodge's membership for many years.[32] The club and lodge have never been formally connected except in name.[34] Lodge membership is not restricted to Savage Club members; however, most who join still have a professional life in literature, art, drama, music, science or law.[34] Founders of the Savage Club Lodge

References

External links

See also |

||||||||||