|

Samuel Chandler

Samuel Chandler (1693 – 8 May 1766) was an English Nonconformist minister and pamphleteer. He has been called the "uncrowned patriarch of Dissent" in the latter part of George II's reign.[1] Early lifeSamuel Chandler was born at Hungerford in Berkshire, the son of Henry Chandler (d.1719), a Dissenting minister, and his wife Mary Bridgeman.[2][3] His father was the first settled Presbyterian minister at Hungerford since the Toleration Act 1688. In or around 1700 the family moved to Bath, where for the remainder of his life Henry ministered to the congregation that met at Frog Lane. He was the younger brother of the Bath poet Mary Chandler, whose biography he wrote for inclusion in Theophilus Cibber's The Lives of the Poets (1753).[4] As a child he displayed an 'early genius for learning',[5] and this was encouraged by his family. He excelled in the classics and is said to have already mastered Greek by the time he entered the dissenting academy at Bridgwater, where he was a student of the Rev John Moore (d.1747). He later attended Samuel Jones' academy at Gloucester. Here he was a contemporary of Bishop Butler and Archbishop Secker, who in spite of their later churchmanship and high preferment remained life-long friends. CareerIn 1714, Chandler began a preaching ministry in London. During this time he shared a house with Secker, who had returned to England after studying in Leiden. In 1716, he was chosen as minister of the Presbyterian Hanover Chapel in Peckham and ordained in December of that year.[6] Through the South Sea Bubble crash of 1720, Chandler lost the fortune which his wife had brought to their marriage. This left him in straitened circumstances, and from about 1723 he supplemented his income by working as a bookseller at the Cross Keys in the Poultry, London.[7] In 1725, having read his recently published A Vindication of the Christian Religion, Archbishop Wake wrote to him expressing surprise that 'so much good learning and just reasoning in a person of your profession, and do think it pity you should not rather spend your time in writing books than in selling them'.[7] It was partly due to the success of A Vindication, which brought together sermons he had delivered at the Old Jewry Meeting-house in defence of Christian revelation, that Chandler was invited to be the assistant minister under Thomas Leavesley at the Old Jewry in 1726. During this time he continued to preach at Peckham. In 1728 he was appointed pastor at the Old Jewry, the congregation offering him an extra £100 a year on the condition that he give up bookselling.[2] He held this position for the rest of his life. Over time he came to play a leading role in the affairs of London Dissenters. From 1730 he was a member of the Presbyterian Board, and from 1744 of Dr Williams's Trust. It was largely as a result of his influence, particularly among wealthy dissenters, that a relief society for widows and orphaned children of Protestant dissenting ministers was established in 1733.[8][2] In a similar way he co-ordinated the formation of The Society for the Propagation of the Knowledge of God among the Germans, formed in 1753 to assist German dissenters in the British Colony of Pennsylvania.[9] Beliefs and writingsChandler was an extensive writer, and through his pamphlets, sermons and letters he engaged energetically with the religious disputes of the day. He was an impassioned proponent of civil and religious liberty, advocating freedom of conscience and the appeal to reason in matters of belief.

His work appears to owe a particular debt to the Christian philosopher Samuel Clarke, and stands broadly in the Lockean tradition. Subscription, penal laws and comprehensionTheologically Chandler belonged to the liberal wing of Dissent. He believed in the sufficiency of a reasoned approach to Scripture, and was hostile to the claims of human tradition and authority. As such, he was among those who argued against the imposition of creeds or articles of faith as tests of orthodoxy. In the Salters' Hall meetings of 1719, which concerned themselves with subscription to the doctrine of the Trinity, he was among the non-subscribing majority. Chandler's Trinitarian theology is said to have derived from Samuel Clarke's The Scripture-Doctrine of the Trinity (1712), and he is often described as an Arian, or having Arian leanings.[11] In the introduction to his translation of Philipp van Limborch's Historia Inquistionis (1731) he discusses subscription at some length, where he describes the practice as having 'ever been a Grievance in the Church of God'.[12] He took up the subject again in anonymous contributions to the Old Whig periodical in 1737. Subsequent debates led to the publication of The Case of Subscription to Explanatory Articles of Faith (1748). In a number of works published in the 1730s Chandler challenged the penal laws governing Dissenters, which through various tests and subscriptions barred them from full participation in civic life. In 1732 he supported those petitioning parliament for their repeal with a pamphlet entitled The Dispute Better Adjusted, and in his 1735 sermons against Roman Catholicism earned the censure of several Anglicans for his 'unseasonal' demands for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts.[13] This was followed by The Case of the Protestant Dissenters (1736) and an open letter to the Lord Mayor of London in 1738.[14] By the time he published The Case of Subscription Chandler was expressing his disinclination to engage in any further 'publick Debates concerning Party Affairs'.[15] Time had 'softened' his mind on such issues, and establishing a common front against the 'impieties of the present generation' was of more importance. Besides ties of friendship, he shared a common outlook with the Latitudinarian leaders of the Anglican Church, and spoke warmly of his relations with them. In the same year he was engaged in informal discussions with Thomas Herring, Thomas Gooch and Thomas Sherlock about the possibility of an act of comprehension, which would enable Dissenters to enter the Established fold in good conscience. To overcome doctrinal objections he suggested that the church's articles by re-written in scriptural language, and that the Athanasian Creed ought to be discarded. These overly ambitious proposals came to nothing, and Chandler came under fire from fellow Dissenters for acting with presumption.[16] DeismIn A Vindication of the Christian Religion (1725) and Reflections on the Conduct of Modern Deists (1727) he defended the scriptural, revealed basis of Christianity against attacks by deists, particularly Anthony Collins. This focused on the argument from miracles and prophecy. At the same time he upheld his opponents' right of conscience and expression against those calling for their censorship. In 1741 he entered once again into the deist controversy with A Vindication of the History of the Old Testament. This was a response to Thomas Morgan's The Moral Philosopher (1738-1740), whose third volume included a character assassination of Joseph. Chandler followed A Vindication with his Defence of the Prime Ministry and Character of Joseph (1743). The debate also promoted a contribution from the deist Peter Annet, who in the same year published his The Resurrection of Jesus Considered (1744). Continuing on from the work of Thomas Woolston in the 1720s, it questioned the reliability of the gospel accounts of the Resurrection. Chandler's answer was contained in The Witnesses of the Resurrection of Jesus re-examined, and their testimony proved entirely consistent (London, 1744). John Leland, in his overview of deist writers, called it a 'very valuable treatise' that showed 'great clearness and judgement'.[17] His apologetic, Plain Reasons for Being a Christian (London, 1730), was a more indirect reply to freethinking critiques of Christianity. It was advanced on the same grounds, however, making its appeal to 'the Truth and Reason of Things' arrived at by a 'free and rational Choice'.[18] Like Clarke, he argued that human reason, which is capable of arriving at natural religion, needed to be supplemented by revelation. But the test of this revelation would be its consistency with reason. Roman CatholicismChandler was vehement in his opposition to Roman Catholicism, and this was sharpened by events which seem to threaten the Protestant Revolution of 1688. In 1735 he took part in a series of controversial lectures organised by Dissenters at Salters' Hall in London, aimed at what they perceived to be the growing threat of "popery", particularly from missionaries. His contributions were published in Seventeen Sermons against Popery preached at Salter's Hall (London, 1735), as well as separately. These advanced a Protestant ecclesiology over and against claims of Roman supremacy, embodied in Bellarmine's fifteen Marks of the Church. As well as being accused by Richard Challoner of wilfully misrepresenting Roman Catholicism, Chandler's sermons were among those that drew criticism from Anglicans. While supportive of his purposes, they took issue with his remarks on the episcopacy ('The Mission of Bishops and Prelates is in itself a trifling Circumstance, of little or not importance...'[19]) and apostolic succession. Shortly afterwards Chandler joined John Eames and Jeremiah Hunt in talks with two Roman priests at the Bell tavern in Nicholas Lane, London. The debate ranged over issues such as the authority of the Pope, transubstantiation, and praying to saints and angels. An account of the second conference was written by Chandler and published by John Gray, his successor at the Cross Keys.[20] Recognition In his Biographia Britannica (1778-1793) the minister Andrew Kippis, who worked on some of his literary remains, described Chandler as:

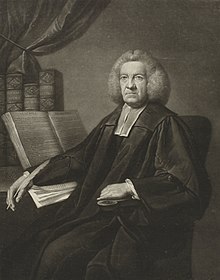

In a letter of 1747 Archbishop Herring wrote of Chandler that 'I really affect and honour the man, and wish with all my soul that the Church of England had him; for his spirit and learning are certainly of the first class'.[22] He had been offered high and lucrative preferment in the Church of England, but chose to remain a Presbyterian to the end of his life on the grounds of conscience. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in December 1754.[23] The only known portrait of Chandler, executed by Mason Chamberlin, was bequeathed to the Royal Society by his brother, the apothecary John Chandler FRS. He was also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquarians. In common with other respected Dissenters he was made a Doctor of Divinity by both Edinburgh University (1755) and King's College, Aberdeen (1756). In the past Chandler had turned down honorary degrees because, as he put it, "so many blockheads had been made Doctors".[24] DeathChandler died on 8 May 1766. During the last year of his life he had suffered from re-occurrences of a 'very painful disorder'.[25] He was buried in what became the family vault at Bunhill Fields in London on 16 May. His funeral sermon was preached at the Old Jewry by his friend, Thomas Amory. Amory later wrote a short memoir of Chandler to preface his posthumously published sermons, and together with Nathaniel White replaced him as a co-pastor at the Old Jewry. FamilyOn 17 September 1719, Chandler married Elizabeth Rutter at St Giles' Church, Camberwell.[26] Elizabeth was the daughter of Benjamin Rutter, leather dresser of Bermondsey, and his wife Elizabeth.[27] They had six children: Elizabeth (d. before 1772), wife of Thomas Mitchell, tailor of Bucklersbury, London;[28][29] Sarah (d.1791), wife of the classical scholar Edward Harwood (1729-1794);[30] Catherine ("Kitty"), wife of William Ward, packer of Sise-lane, London,[31] and Mary ("Polly"), who remained unmarried. His two sons pre-deceased him. Chandler's widow died in 1773. In her will she left £1860 in individual bequests. The residue of her estate went to her daughter Mary.[32] Works

Sermons and pamphlets

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chandler, Samuel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 838. |

||||||||||