|

Royal forest

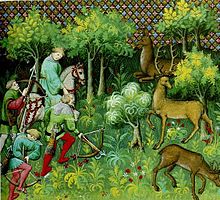

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (Latin: silva regis),[1][2] is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The term forest in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the original medieval sense was closer to the modern idea of a "preserve" – i.e. land legally set aside for specific purposes such as royal hunting – with less emphasis on its composition. There are also differing and contextual interpretations in Continental Europe derived from the Carolingian and Merovingian legal systems.[3] In Anglo-Saxon England, though the kings were great huntsmen, they never set aside areas declared to be "outside" (Latin foris) the law of the land.[4] Historians find no evidence of the Anglo-Saxon monarchs (c. 500 to 1066) creating forests.[5] However, under the Norman kings (after 1066), by royal prerogative forest law was widely applied.[6] The law was designed to protect the "venison and the vert". In this sense, venison meant "noble" animals of the chase – notably red and fallow deer, the roe deer, and wild boar – and vert meant the greenery that sustained them. Forests were designed as hunting areas reserved for the monarch or (by invitation) the aristocracy. The concept was introduced by the Normans to England in the 11th century, and at the height of this practice in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, fully one-third of the land area of Southern England was designated as royal forest. At one stage in the 12th century, all of Essex was afforested. On accession Henry II declared all of Huntingdonshire to be a royal forest.[4] Afforestation, in particular the creation of the New Forest, figured large in the folk history of the "Norman yoke", which magnified what was already a grave social ill: "the picture of prosperous settlements disrupted, houses burned, peasants evicted, all to serve the pleasure of the foreign tyrant, is a familiar element in the English national story .... The extent and intensity of hardship and of depopulation have been exaggerated", H. R. Loyn observed.[4] Forest law prescribed harsh punishment for anyone who committed any of a range of offences within the forests; by the mid-17th century, enforcement of this law had died out, but many of England's woodlands still bore the title "Royal Forest". During the Middle Ages, the practice of reserving areas of land for the sole use of the aristocracy was common throughout Europe. Royal forests usually included large areas of heath, grassland and wetland – anywhere that supported deer and other game. In addition, when an area was initially designated forest, any villages, towns and fields that lay within it were also subject to forest law. This could foster resentment as the local inhabitants were then restricted in the use of land they had previously relied upon for their livelihoods; however, common rights were not extinguished, but merely curtailed.[7] Areas chosen for royal forestsThe areas that became royal forests were already relatively wild and sparsely populated, and can be related to specific geographic features that made them harder to work as farmland. In the South West of England, forests extended across the Upper Jurassic Clay Vale.[8] In the Midlands, the clay plain surrounding the River Severn was heavily wooded. Clay soils in Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Huntingdonshire and Northamptonshire formed another belt of woodlands. In Hampshire, Berkshire and Surrey, woodlands were established on sandy, gravelly, acid soils. In the Scots Highlands, a "deer forest" generally has no trees at all. Marshlands in Lincolnshire were afforested.[9] Upland moors too were chosen, such as Dartmoor and Exmoor in the South West, and the Peak Forest of Derbyshire. The North Yorkshire moors, a sandstone plateau, had a number of royal forests.[8] Forest law William the Conqueror, a great lover of hunting, established the system of forest law. This operated outside the common law, and served to protect game animals and their forest habitat from destruction. In the year of his death, 1087, a poem, "The Rime of King William", inserted in the Peterborough Chronicle, expresses English indignation at the forest laws. OffencesOffences in forest law were divided into two categories: trespass against the vert (the vegetation of the forest) and trespass against the venison (the game). The five animals of the forest protected by law were given by Manwood as the hart and hind (i.e. male and female red deer), boar, hare and wolf. (In England, the boar became extinct in the wild by the 13th century, and the wolf by the late 15th century.) Protection was also said to be extended to the beasts of chase, namely the buck and doe (fallow deer), fox, marten, and roe deer, and the beasts and fowls of warren: the hare, coney, pheasant, and partridge.[10] In addition, inhabitants of the forest were forbidden to bear hunting weapons, and dogs were banned from the forest; mastiffs were permitted as watchdogs, but they had to have their front claws removed to prevent them from hunting game. The rights of chase and of warren (i.e. to hunt such beasts) were often granted to local nobility for a fee, but were a separate concept. Trespasses against the vert were extensive: they included purpresture, assarting, clearing forest land for agriculture, and felling trees or clearing shrubs, among others. These laws applied to any land within the boundary of the forest, even if it were freely owned; although the Charter of the Forest in 1217 established that all freemen owning land within the forest enjoyed the rights of agistment and pannage. Under the forest laws, bloody hand was a kind of trespass by which the offender, being apprehended and found with his hands or other body part stained with blood, is judged to have killed the deer, even though he was not found hunting or chasing.[11] Disafforested lands on the edge of the forest were known as purlieus; agriculture was permitted here and deer escaping from the forest into them were permitted to be killed if causing damage. Rights and privilegesPayment for access to certain rights could provide a useful source of income. Local nobles could be granted a royal licence to take a certain amount of game. The common inhabitants of the forest might, depending on their location, possess a variety of rights: estover, the right of taking firewood; pannage, the right to pasture swine in the forest; turbary, the right to cut turf (as fuel); and various other rights of pasturage (agistment) and harvesting the products of the forest. Land might be disafforested entirely, or permission given for assart and purpresture. OfficersThe justices of the forest were the justices in eyre and the verderers. The chief royal official was the warden. As he was often an eminent and preoccupied magnate, his powers were frequently exercised by a deputy. He supervised the foresters and under-foresters, who personally went about preserving the forest and game and apprehending offenders against the law. The agisters supervised pannage and agistment and collected any fees thereto appertaining. The nomenclature of the officers can be somewhat confusing: the rank immediately below the constable was referred to as foresters-in-fee, or, later, woodwards, who held land in the forest in exchange for rent, and advised the warden. They exercised various privileges within their bailiwicks. Their subordinates were the under-foresters, later referred to as rangers. The rangers are sometimes said to be patrollers of the purlieu. Another group, called serjeants-in-fee, and later, foresters-in-fee (not to be confused with the above), held small estates in return for their service in patrolling the forest and apprehending offenders. The forests also had surveyors, who determined the boundaries of the forest, and regarders. These last reported to the court of justice-seat and investigated encroachments on the forest and invasion of royal rights, such as assarting. While their visits were infrequent, due to the interval of time between courts, they provided a check against collusion between the foresters and local offenders. CourtsBlackstone gives the following outline of the forest courts, as theoretically constructed:

In practice, these fine distinctions were not always observed. In the Forest of Dean, swainmote and the court of attachment seem to have been one and the same throughout most of its history. As the courts of justice-seat were held less frequently, the lower courts assumed the power to fine offenders against the forest laws, according to a fixed schedule. The courts of justice-seat crept into disuse, and in 1817, the office of justice in eyre was abolished and its powers transferred to the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests. Courts of swainmote and attachment went out of existence at various dates in the different forests. A Court of Swainmote was re-established in the New Forest in 1877. HistorySince the conquest of England, the forest, chase and warren lands had been exempted from the common law and subject only to the authority of the king, but these customs had faded into obscurity by the time of The Restoration.[12] William the ConquerorWilliam I, original enactor of the Forest Law in England, did not harshly penalise offenders. The accusation that he "laid a law upon it, that whoever slew hart or hind should be blinded," according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is little more than propaganda. William Rufus, also a keen hunter, increased the severity of the penalties for various offences to include death and mutilation. The laws were in part codified under the Assize of the Forest (1184)[13] of Henry II. Magna CartaMagna Carta, the charter forced upon King John of England by the English barons in 1215, contained five clauses relating to royal forests. They aimed to limit, and even reduce, the King's sole rights as enshrined in forest law. The clauses were as follows (taken from translation of the great charter that is the Magna Carta):[14]

Charter of the ForestAfter the death of John, Henry III was compelled to grant the Charter of the Forest (1217), which further reformed the forest law and established the rights of agistment and pannage on private land within the forests. It also checked certain of the extortions of the foresters. An "Ordinance of the Forest" under Edward I again checked the oppression of the officers and introduced sworn juries in the forest courts. Great Perambulation and afterIn 1300 many (if not all) forests were perambulated and reduced greatly in their extent, in theory to their extent in the time of Henry II. However, this depended on the determination of local juries, whose decisions often excluded from the Forest lands described in Domesday Book as within the forest. Successive kings tried to recover the "purlieus" excluded from a forest by the Great Perambulation of 1300. Forest officers periodically fined the inhabitants of the purlieus for failing to attend Forest Court or for forest offences. This led to complaints in Parliament. The king promised to remedy the grievances, but usually did nothing. Several forests were alienated by Richard II and his successors, but generally the system decayed. Henry VII revived "Swainmotes" (forest courts) for several forests and held Forest Eyres in some of them. Henry VIII in 1547 placed the forests under the Court of Augmentations with two Masters and two Surveyors-General. On the abolition of that court, the two surveyors-general became responsible to the Exchequer. Their respective divisions were north and south of the River Trent. The last serious exercise of forest law by a court of justice-seat (Forest Eyre) seems to have been in about 1635, in an attempt to raise money. Disafforestation, sale of forest lands and the Western Rising

By the Tudor period and after, forest law had largely become anachronistic, and served primarily to protect timber in the royal forests. James I and his ministers Robert Cecil and Lionel Cranfield pursued a policy of increasing revenues from the forests and starting the process of disafforestation.[20] Cecil made the first steps towards abolition of the forests, as part of James I's policy of increasing his income independently of Parliament. Cecil investigated forests that were unused for royal hunting and provided little revenue from timber sales. Knaresborough Forest in Yorkshire was abolished. Revenues in the Forest of Dean were increased through sales of wood for iron smelting. Enclosures were made in Chippenham and Blackmore for herbage and pannage.[20] Cranfield commissioned surveys into assart lands of various forests, including Feckenham, Sedgemoor and Selwood, laying the foundations of the wide-scale abolition of forests under Charles I. The commissioners appointed raised over £25,000 by compounding with occupiers, whose ownership was confirmed, subject to a fixed rent. Cranfield's work led directly to the disafforestation of Gillingham Forest in Dorset and Chippenham and Blackmore in Wiltshire. Additionally, he created the model for the abolition of the forests followed throughout the 1630s.[21] Each disafforestation would start with a commission from the Exchequer, which would survey the forest, determine the lands belonging to the crown, and negotiate compensation for landowners and tenants whose now-traditional rights to use of the land as commons would be revoked. A legal action by the Attorney General would then proceed in the Court of Exchequer against the forest residents for intrusion, which would confirm the settlement negotiated by the commission. Crown lands would then be granted (leased), usually to prominent courtiers, and often the same figures that had undertaken the commission surveys. Legal complaints about the imposed settlements and compensation were frequent.[21] The disafforestations caused riots and Skimmington processions resulting in the destruction of enclosures and reoccupation of grazing lands in a number of West Country forests, including Gillingham, Braydon and Dean, known as the Western Rising. Riots also took place in Feckenham, Leicester and Malvern. The riots followed the physical enclosure of lands previously used as commons, and frequently led to the destruction of fencing and hedges. Some were said to have had a "warlike" character, with armed mobs numbering hundreds, for instance in Feckenham. The rioters in Dean fully destroyed the enclosures surrounding 3,000 acres in groups that numbered thousands of participants. The disturbances tended to involve artisans and cottagers who were not entitled to compensation. The riots were hard to enforce against, due to the lack of efficient militia, and the low-born nature of the participants.[22] Ultimately, however, enclosure succeeded, with the exceptions of Dean and Malvern Chase. In 1641, Parliament passed the Delimitation of Forests Act 1640 (16 Cha. 1. c. 16, also known as Selden's Act) to revert the forest boundaries to the positions they had held at the end of the reign of James I.[18] After the RestorationThe Forest of Dean was legally re-established in 1668 by the Dean Forest Act 1667.[23] A Forest Eyre was held for the New Forest in 1670, and a few for other forests in the 1660s and 1670s, but these were the last. From 1715, both surveyors' posts were held by the same person. The remaining royal forests continued to be managed (in theory, at least) on behalf of the Crown. However, the commoners' rights of grazing often seem to have been more important than the rights of the Crown. In the late 1780s, a royal commission was appointed to inquire into the condition of crown woods and those surviving. North of the Trent it found Sherwood Forest survived, south of it: the New Forest, three others in Hampshire, Windsor Forest in Berkshire, the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, Waltham or Epping Forest in Essex, three forests in Northamptonshire, and Wychwood in Oxfordshire. Some of these no longer had swainmote courts thus no official supervision. They divided the remaining forests into two classes, those with and without the Crown as major landowner. In certain Hampshire forests and the Forest of Dean, most of the soil belonged to the Crown and these should be reserved to grow timber, to meet the need for oak for shipbuilding. The others would be inclosed, the Crown receiving an "allotment" (compensation) in lieu of its rights. In 1810, responsibility for woods was moved from Surveyors-General (who accounted to the Auditors of Land Revenue) to a new Commission of Woods, Forests, and Land Revenues. From 1832 to 1851 "Works and Buildings" were added to their responsibilities. In 1851, the commissioners again became a Commissioner of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues. In 1924, the Royal Forests were transferred to the new Forestry Commission (now Forestry England). Surviving ancient forests Forest of DeanThe Forest of Dean was used as a source of charcoal for ironmaking within the Forest from 1612 until about 1670. It was the subject of a Reafforestation Act in 1667. Courts continued to be held at the Speech House, for example, to regulate the activities of the Freeminers. The sale of cordwood for charcoal continued until at least the late 18th century. Deer were removed in 1850. The forest is today heavily wooded, as is a substantial formerly privately owned area to the west, now treated as part of the forest. It is managed by Forestry England. Epping & Hainault ForestsEpping and Hainault Forest are surviving remnants of the Royal Forest of Waltham.[24] The extent of Epping and Hainault Forests was greatly reduced by inclosure by landowners. The Hainault Forest Act 1851 was passed by Parliament, ending the Royal protection for Hainault Forest. Within six weeks 3000 acres of woodland was cleared.[25] The Corporation of London wished to see Epping Forest preserved as an open space and obtained an injunction in 1874[26] to throw open some 3,000 acres (12 km2) that had been inclosed in the preceding 20 years. In 1875 and 1876, the corporation bought 3,000 acres (12 km2) of open wasteland. Under the Epping Forest Act 1878, the forest was disafforested and forest law was abolished in respect of it. Instead, the corporation was appointed as Conservators of the Forest. The forest is managed through the Epping Forest Committee. New ForestThe New Forest is home to the British cultural minority known as New Forest Commoners. An Act was passed to remove the deer in 1851, but abandoned when it was realised that the deer were needed to keep open the unwooded "lawns" of the forest. An attempt was made to develop the forest for growing wood by a rolling programme of inclosures. In 1875, a Select committee of the House of Commons recommended against this, leading to the passage of the New Forest Act 1877, which limited the Crown's right to inclose, regulated common rights, and reconstituted the Court of Verderers. A further Act was passed in 1964. This forest is also managed by Forestry England. Sherwood ForestA forest since the end of the Ice Age (as attested by pollen sampling cores), Sherwood Forest National Nature Reserve today encompasses 423.2 hectares,[27] (1,045 acres) surrounding the village of Edwinstowe, the site of Thoresby Hall. The core of the forest[citation needed] is the Special Area of Conservation named Birklands and Bilhaugh.[28] It is a remnant of an older, much larger, royal hunting forest, which derived its name from its status as the shire (or sher) wood of Nottinghamshire, which extended into several neighbouring counties (shires), bordered on the west along the River Erewash and the Forest of East Derbyshire. When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, the forest covered perhaps a quarter of Nottinghamshire in woodland and heath subject to the forest laws. Royal forests by countyEngland

IrelandOnly one royal forest is known to have been formed in the Lordship of Ireland.

See also

ReferencesSpecific

Bibliography

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||