|

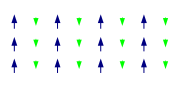

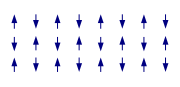

Rock magnetism Rock magnetism is the study of the magnetic properties of rocks, sediments and soils. The field arose out of the need in paleomagnetism to understand how rocks record the Earth's magnetic field. This remanence is carried by minerals, particularly certain strongly magnetic minerals like magnetite (the main source of magnetism in lodestone). An understanding of remanence helps paleomagnetists to develop methods for measuring the ancient magnetic field and correct for effects like sediment compaction and metamorphism. Rock magnetic methods are used to get a more detailed picture of the source of the distinctive striped pattern in marine magnetic anomalies that provides important information on plate tectonics. They are also used to interpret terrestrial magnetic anomalies in magnetic surveys as well as the strong crustal magnetism on Mars. Strongly magnetic minerals have properties that depend on the size, shape, defect structure and concentration of the minerals in a rock. Rock magnetism provides non-destructive methods for analyzing these minerals such as magnetic hysteresis measurements, temperature-dependent remanence measurements, Mössbauer spectroscopy, ferromagnetic resonance and so on. With such methods, rock magnetists can measure the effects of past climate change and human impacts on the mineralogy (see environmental magnetism). In sediments, a lot of the magnetic remanence is carried by minerals that were created by magnetotactic bacteria, so rock magnetists have made significant contributions to biomagnetism. HistoryUntil the 20th century, the study of the Earth's field (geomagnetism and paleomagnetism) and of magnetic materials (especially ferromagnetism) developed separately. Rock magnetism had its start when scientists brought these two fields together in the laboratory.[1] Koenigsberger (1938), Thellier (1938) and Nagata (1943) investigated the origin of remanence in igneous rocks.[1] By heating rocks and archeological materials to high temperatures in a magnetic field, they gave the materials a thermoremanent magnetization (TRM), and they investigated the properties of this magnetization. Thellier developed a series of conditions (the Thellier laws) that, if fulfilled, would allow the determination of the intensity of the ancient magnetic field to be determined using the Thellier–Thellier method. In 1949, Louis Néel developed a theory that explained these observations, showed that the Thellier laws were satisfied by certain kinds of single-domain magnets, and introduced the concept of blocking of TRM.[2] When paleomagnetic work in the 1950s lent support to the theory of continental drift,[3][4] skeptics were quick to question whether rocks could carry a stable remanence for geological ages.[5] Rock magnetists were able to show that rocks could have more than one component of remanence, some soft (easily removed) and some very stable. To get at the stable part, they took to "cleaning" samples by heating them or exposing them to an alternating field. However, later events, particularly the recognition that many North American rocks had been pervasively remagnetized in the Paleozoic,[6] showed that a single cleaning step was inadequate, and paleomagnetists began to routinely use stepwise demagnetization to strip away the remanence in small bits. FundamentalsTypes of magnetic orderThe contribution of a mineral to the total magnetism of a rock depends strongly on the type of magnetic order or disorder. Magnetically disordered minerals (diamagnets and paramagnets) contribute a weak magnetism and have no remanence. The more important minerals for rock magnetism are the minerals that can be magnetically ordered, at least at some temperatures. These are the ferromagnets, ferrimagnets and certain kinds of antiferromagnets. These minerals have a much stronger response to the field and can have a remanence. DiamagnetismDiamagnetism is a magnetic response shared by all substances. In response to an applied magnetic field, electrons precess (see Larmor precession), and by Lenz's law they act to shield the interior of a body from the magnetic field. Thus, the moment produced is in the opposite direction to the field and the susceptibility is negative. This effect is weak but independent of temperature. A substance whose only magnetic response is diamagnetism is called a diamagnet. ParamagnetismParamagnetism is a weak positive response to a magnetic field due to rotation of electron spins. Paramagnetism occurs in certain kinds of iron-bearing minerals because the iron contains an unpaired electron in one of their shells (see Hund's rules). Some are paramagnetic down to absolute zero and their susceptibility is inversely proportional to the temperature (see Curie's law); others are magnetically ordered below a critical temperature and the susceptibility increases as it approaches that temperature (see Curie–Weiss law). Ferromagnetism Collectively, strongly magnetic materials are often referred to as ferromagnets. However, this magnetism can arise as the result of more than one kind of magnetic order. In the strict sense, ferromagnetism refers to magnetic ordering where neighboring electron spins are aligned by the exchange interaction. The classic ferromagnet is iron. Below a critical temperature called the Curie temperature, ferromagnets have a spontaneous magnetization and there is hysteresis in their response to a changing magnetic field. Most importantly for rock magnetism, they have remanence, so they can record the Earth's field. Iron does not occur widely in its pure form. It is usually incorporated into iron oxides, oxyhydroxides and sulfides. In these compounds, the iron atoms are not close enough for direct exchange, so they are coupled by indirect exchange or superexchange. The result is that the crystal lattice is divided into two or more sublattices with different moments.[1] Ferrimagnetism Ferrimagnets have two sublattices with opposing moments. One sublattice has a larger moment, so there is a net unbalance. Magnetite, the most important of the magnetic minerals, is a ferrimagnet. Ferrimagnets often behave like ferromagnets, but the temperature dependence of their spontaneous magnetization can be quite different. Louis Néel identified four types of temperature dependence, one of which involves a reversal of the magnetization. This phenomenon played a role in controversies over marine magnetic anomalies. Antiferromagnetism Antiferromagnets, like ferrimagnets, have two sublattices with opposing moments, but now the moments are equal in magnitude. If the moments are exactly opposed, the magnet has no remanence. However, the moments can be tilted (spin canting), resulting in a moment nearly at right angles to the moments of the sublattices. Hematite has this kind of magnetism. Magnetic mineralogyTypes of remanenceMagnetic remanence is often identified with a particular kind of remanence that is obtained after exposing a magnet to a field at room temperature. However, the Earth's field is not large, and this kind of remanence would be weak and easily overwritten by later fields. A central part of rock magnetism is the study of magnetic remanence, both as natural remanent magnetization (NRM) in rocks obtained from the field and remanence induced in the laboratory. Below are listed the important natural remanences and some artificially induced kinds. Thermoremanent magnetization (TRM)When an igneous rock cools, it acquires a thermoremanent magnetization (TRM) from the Earth's field. TRM can be much larger than it would be if exposed to the same field at room temperature (see isothermal remanence). This remanence can also be very stable, lasting without significant change for millions of years. TRM is the main reason that paleomagnetists are able to deduce the direction and magnitude of the ancient Earth's field.[7] If a rock is later re-heated (as a result of burial, for example), part or all of the TRM can be replaced by a new remanence. If it is only part of the remanence, it is known as partial thermoremanent magnetization (pTRM). Because numerous experiments have been done modeling different ways of acquiring remanence, pTRM can have other meanings. For example, it can also be acquired in the laboratory by cooling in zero field to a temperature (below the Curie temperature), applying a magnetic field and cooling to a temperature , then cooling the rest of the way to room temperature in zero field. The standard model for TRM is as follows. When a mineral such as magnetite cools below the Curie temperature, it becomes ferromagnetic but is not immediately capable of carrying a remanence. Instead, it is superparamagnetic, responding reversibly to changes in the magnetic field. For remanence to be possible there must be a strong enough magnetic anisotropy to keep the magnetization near a stable state; otherwise, thermal fluctuations make the magnetic moment wander randomly. As the rock continues to cool, there is a critical temperature at which the magnetic anisotropy becomes large enough to keep the moment from wandering: this temperature is called the blocking temperature and referred to by the symbol . The magnetization remains in the same state as the rock is cooled to room temperature and becomes a thermoremanent magnetization. Chemical (or crystallization) remanent magnetization (CRM)Magnetic grains may precipitate from a circulating solution, or be formed during chemical reactions, and may record the direction of the magnetic field at the time of mineral formation. The field is said to be recorded by chemical remanent magnetization (CRM). The mineral recording the field commonly is hematite, another iron oxide. Redbeds, clastic sedimentary rocks (such as sandstones) that are red primarily because of hematite formation during or after sedimentary diagenesis, may have useful CRM signatures, and magnetostratigraphy can be based on such signatures. Depositional remanent magnetization (DRM)Magnetic grains in sediments may align with the magnetic field during or soon after deposition; this is known as detrital remanent magnetization (DRM). If the magnetization is acquired as the grains are deposited, the result is a depositional detrital remanent magnetization (dDRM); if it is acquired soon after deposition, it is a post-depositional detrital remanent magnetization (pDRM). Viscous remanent magnetizationViscous remanent magnetization (VRM), also known as viscous magnetization, is remanence that is acquired by ferromagnetic minerals by sitting in a magnetic field for some time. The natural remanent magnetization of an igneous rock can be altered by this process. To remove this component, some form of stepwise demagnetization must be used.[1] Applications of rock magnetismNotes

References

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Rock magnetism. |