|

Irish composer and organist

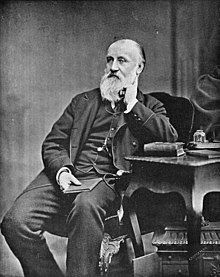

Robert Prescott Stewart |

|---|

Sir Robert Prescott Stewart | | Born | 16 December 1825

Dublin |

|---|

| Died | 24 March 1894 (age 68)

Dublin |

|---|

| Occupation(s) | Composer and organist |

|---|

Sir Robert Prescott Stewart (16 December 1825 – 24 March 1894) was an Irish composer, organist, conductor, and teacher – one of the most influential (classical) musicians in 19th-century Ireland.

Biography

Stewart was born in Dublin; his grandfather had moved to Ireland from the Lowlands of Scotland in 1780.[1] He displayed an early talent for music, fostered by his mother, who had been a pupil of Johann Bernhard Logier. He didn't study music in an academic sense, but received some thorough grounding in church music when he joined the choir school of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, in 1833, where he came under the care and tutelage of Rev. John Finlayson and the Master of the Boys, Richard William Beaty.[2] His biographer O.J. Vignoles also mentions Archdeacon Magee and the Dean's vicar, John C. Crosthwaite, as having had influence on Stewart's musical education.[3] In 1844 he succeeded John Robinson as cathedral organist, a position he held until his death, and also became organist at St. Patrick's Cathedral from 1852 to 1861. In 1846 he succeeded Joseph Robinson as conductor of the University of Dublin Choral Society, another position he held for the rest of his life. He received the degrees of Bachelor of Music (MusB) and Doctor of Music (MusD) from Trinity College, Dublin, simultaneously in April 1851 and became Professor of Music there in 1862 (again until the end of his life). In addition, Stewart was professor of piano, organ, harmony and counterpoint at the Royal Irish Academy of Music from 1869, also teaching chamber music classes there from 1880. He was a founder, in 1865, of the Dublin Glee and Madrigal Union and conducted the Philharmonic Society (Dublin) and the Belfast Philharmonic Society. For his services to music he was knighted at Dublin Castle in 1872. He died in Dublin.

Among Stewart's most prominent pupils were Annie Curwen, W. H. Grattan Flood, Vincent O'Brien, Margaret O'Hea, Edith Oldham, Annie Patterson, Charles Villiers Stanford, and the writer John Millington Synge.

Music

In the light of all these positions, activities, and commitments it is difficult to imagine how Stewart found time for composing music. Yet, he was very prolific in this regard, too. Although he didn't write any symphonies or concertante works for orchestra, he concentrated on vocal music including large-scale cantatas, small-scale glees, songs and a number of organ pieces. His largest works are the cantatas A Winter Night's Wake (1858) and The Eve of St John (1860), the Ode to Shakespeare (1870) for the Birmingham Festival, an Orchestral Fantasia (1872) for the Boston Peace Festival, and the Tercentenary Ode (1892) for the anniversary of Trinity College, Dublin. Many of these works are difficult to assess today, because Stewart was extremely critical of his own output, and destroyed a lot of it, including the Ode to Shakespeare.

Stewart also made an international reputation as a performer and extemporiser on the organ. Beginning with an 1851 performance at the Crystal Palace on the occasion of the London Exhibition, he played in England on numerous occasions, including several journeys to the Birmingham Music Festivals, the Manchester Exhibition, and he also travelled to the Beethoven and Schumann festivals in Bonn and the Wagner Festival at Bayreuth. For most of the twentieth century, Stewart's music was regarded as uninspired and academic, or, as a writer put it in 1989: "[...] generally a model of rectitude, but the absence of that creative spark which, after all, belongs only to a select few in any generation has doomed it to an almost total oblivion from which it is unlikely to emerge."[4]

During recent years there has been a revived interest in Stewart's music, particularly his church music, and he has regained a firm place in the Irish cathedral repertoire today. This newfound esteem is reflected in a number of 1990s CD recordings (see 'Recordings' below). Boydell wrote in 2004: "Stewart is beginning to be acknowledged as a talented composer who made an important contribution not only to music in nineteenth-century Ireland but also within the wider context of nineteenth-century cathedral music."[5]

Selected compositions

This list is based on the catalogue by genre in Parker (2009), appendix VIIb, pp. 393–401, see Bibliography.

|

Orchestral

- The Exhibition Grand March (1853)

- March for the Installation of the Earl of Rosse as Chancellor of the University of Dublin (1863)

- Orchestral Fantasia (1872)

Chorus and orchestra (or piano)

- Inauguration Ode (Ode to Industry) (John Francis Waller) for chorus and orch. (1852), vocal score published Cork: J.J. Bradford and Dublin: James McGlashan, 1852

- Who shall raise the bell? (The Belfry Cantata) (J.F. Waller) for soloists, chorus and orch. (1854)

- The Eve of St John (J.F. Waller) for 9 soloists, chorus and orch. (1860), vocal score published London: Blockley, 1884

- Installation Ode (J.F. Waller) for soloists, chorus and orch. (1863)

- Ode for the Opening of the 1864 Dublin Exhibition (J.F. Waller) for chorus and orch. (1864)

- Ode to Shakespeare (Henry Toole) for soloists, chorus and orch. (1870)

- How Shall We Close Our Gates? (J.F. Waller) for male soloists, chorus and orch. (1873)

- An Irish Welcome to the American Rifle Team (J.F. Waller) for male chorus and piano (1875), Dublin: Morrison, 1875

- Tercentenary Ode (George Francis Savage-Armstrong) for soloists, chorus and orch. (1892), vocal score London: Novello, 1892

Church music

- Plead Thou My Cause, verse anthem (1843)

- Service in C major (1846)

- Morning and Evening Service in E flat major for soloists, chorus and orch. (1851), vocal score London: Novello, 1881

- O Lord My God, full anthem (c.1859), Dublin: Bussell (n.d.)

- A Voice from Heaven (I Shine in the Light of God), sacred song (1863), London: Novello, 1897

- If Ye Love Me Keep My Commandments, full anthem (1863), London: Novello, 1885

- In the Lord Put I My Trust, full anthem (1863), London: Novello, 1876

- Thou O God Art Praised in Zion, verse anthem (1863), London: Novello, 1876

- Morning and Evening Service in G major (1866), London: Novello, 1866

- Jubilate Deo in G major (1869), London: Novello, 1869

- Veni Creator in B flat major for double choir (1872), London: Metzler & Co. (n.d.)

- The King Shall Rejoice, verse anthem (1887), London: Novello, 1887

- The Breastplate of St Patrick for bass solo and mixed chorus (1888), Dublin: APCK (n.d.)

- almost 20 settings to complete services by other composers

- more than 30 hymn tunes, published, among others, in Chants Ancient and Modern (1868), The Anglican Hymn Book (1871), Church Hymnal (1874), The Irish Church Hymnal (1876), Hymns Ancient and Modern (1888).

|

Instrumental music

- The Exhibition Grand March for piano (1853), London: Addison, 1854

- Four Piano Fantasias (1862), London: Bussell (1862). Contains: When the Rosy Morn, Thou Art Coming with the Sunshine, Dormi pur, My Thoughts Will Wander Far Away.

- Concert Fantasia for organ (1868), London: Novello, 1887

- Introduction and Fugue for organ (1882), London: Broadhouse, 1883

- A Little Organ School (1885), ed. A.M. Henderson: London: Bayley and Ferguson, 1946

- Arrangement of the Finale from Symphony No. 3 by Mendelssohn, for organ (c.1889), London: Novello, (n.d.)

- Suite for 3 violins in G major (1890)

Small-scale vocal music

- The Skylark (Go Tuneful Bird), glee (W. Shenstone) (1847), London: Addison and Hollier, 1854

- O Nightingale, partsong (1848), London: Addison & Hollier (n.d.)

- The Dream, partsong w/ piano (A.T.) (1851), London: Novello, 1851

- The Haymaker's Song, partsong w/ piano (Mrs Newton Crosland) (1851), London: Novello, 1851

- I Do Not Mourn over Vanished Years, song (J.F. Waller), London, 1851

- The Fairest Flower (The Dawn of Day is Far Away), partsong w/ piano (J.F. Waller) (1854), London: Novello, 1875

- O Phoebus, glee (Samuel Johnson) (1856), London: Curwen, 1902

- I Must Love Thee Still, Marion, song (J.F. Waller), London: Cramer, Beale & Chappell, 1860

- The Song of the Fairies in the Ruins of Heidelberg (from Lytton's novel The Pilgrims of the Rhine), glee (1869), London: Patey & Willis, 1897

- The Bells of St Michael's Tower, glee w/piano (William Knyvett) (1870), London: Novello, 1880

- The Cruiskeen Lawn (Thomas Moore), partsong w/ piano (1870), London: Novello & Ewer, 1880

- Six Two-Part Songs (Wellington Guernsey, Hammond) (1872). Contains: Joy and Sorrow, Sleep, What is Love?, Harp that Wildly Wreathing Sounds, Religion, Night Hurrying on (the last two published London: Stanley Lucas & Weber, 1881).

- Love Leads Us Captive, terzetto for 2 sopranos, tenor and piano (J.F. Waller) (1858), London: Stanley Lucas & Weber, 1873

- The Reason Why for mixed choir (J.F. Waller) (1874), Dublin: Pohlmann (n.d.)

- Achora Machree, song (Joseph Martin Emerson), London: Chappell, 1878

- How Shall I Think of Thee? (The Question), song (R.W. Cooke-Taylor) (1881), Dublin: Pigot (n.d.)

- How Should'st Thou Think of Me? (The Answer), song (R.W. Cooke-Taylor) (1881), Dublin: Pigot (n.d.)

- O Lovely Night for male choir (J.F. Waller), London: Augener, 1886

- Could I Keep Time from Flying, partsong for male voices (T. Smith) (1889), London: Novello, 1889

|

Recordings

- Deus, repulisti nos (Psalm 60), performed by St Paul's Cathedral Choir, Andrew Lucas (organ), John Scott (cond.), on: Psalms from St Paul's Vol. 5: Psalms 56–68, Hyperion CDP 11005 (CD, 1996).

- Paratum cor meum (Psalm 108), performed by St Paul's Cathedral Choir, Huw Williams (organ), John Scott (cond.), on: Psalms from St Paul's Vol. 9: Psalms 105–113, Hyperion CDP 11009 (CD, 1999).

- If Ye Love Me Keep My Commandments, performed by Christ Church Cathedral Dublin Choir, Andrew Johnstone (organ), Mark Duley (cond.), on: Great Cathedral Anthems Vol. X, Priory Records PRCD 639 (CD, 1999).

- Thou O God Art Praised in Zion, performed by Christ Church Cathedral Dublin Choir, David Adams (organ), Mark Duley (cond.), on: Sing O Ye Heavens. Historic Anthems from Christ Church Cathedral Dublin, Christ Church Cathedral CCCD1 (CD, 1999).

Bibliography

- Vignoles, Olynthus J.: Memoir of Sir Robert P. Stewart (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. and Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., 1898; 2nd ed. 1899).

- Bumpus, John S.: "Irish Church Composers and the Irish Cathedrals", 2 parts, in: Proceedings of the Musical Association 26 (1899–1900), p. 79–93 & 115–59.

- Culwick, James C.: Sir Robert Stewart: With Reminiscences of his Life and Work (Dublin, 1900).

- Culwick, James C.: The Works of Robert Stewart (Dublin, 1902).

- Grindle, William Henry: Irish Cathedral Music (Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, 1989).

- Boydell, Barra: A History of Music at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2004).

- Parker, Lisa: Robert Prescott Stewart (1825–1894): A Victorian Musician in Dublin (Ph.D. thesis, NUI Maynooth, 2009), unpublished, downloadable here.

References

- ^ Vignoles (1898), p. 3; see Bibliography.

- ^ Parker (2009), p. 7.

- ^ Vignoles (1898), p. 5–6.

- ^ Grindle (1989), p. 202; see Bibliography.

- ^ Boydell (2004), p. 166; see Bibliography.

|

|---|

| International | |

|---|

| National | |

|---|

| Artists | |

|---|

| People | |

|---|

| Other | |

|---|

|