|

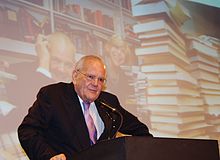

Robert B. Silvers

Robert Benjamin Silvers (December 31, 1929 – March 20, 2017) was an American editor who served as editor of The New York Review of Books from 1963 to 2017. Raised on Long Island, New York, Silvers graduated from the University of Chicago in 1947 and attended Yale Law School, but he left before graduating and worked as press secretary to Chester Bowles in 1950. He was sent by the U.S. Army to Paris in 1952 as a speechwriter and press aide, while finishing his education at the Sorbonne and Sciences Po. He soon joined The Paris Review as an editor under the guidance of George Plimpton. From 1959 to 1963, he was an associate editor of Harper's Magazine in New York. Silvers was co-editor of The New York Review of Books with Barbara Epstein for 43 years, until she died in 2006, and was the sole editor of the paper after that until his own death in 2017. Philip Marino of Liveright Publishing wrote of him: "Like a chemist pairing ingredients to induce a specific reaction, Silvers has built his career matching the right author and subject, in hopes of generating an exciting and illuminating result."[1] Silvers edited or co-edited several essay anthologies. He appeared prominently in the 2014 documentary film about the Review, The 50 Year Argument. Silvers' awards and honorary degrees include the National Book Foundation's Literarian Award, the American Academy of Arts and Letters' Award for "Distinguished Service to the Arts", the Ivan Sandrof Award for Lifetime Achievement in Publishing and a National Humanities Medal. Among other honors, he was a Chevalier of the French Légion d’honneur and a member of the French Ordre National du Mérite. Life and careerEarly life and education Silvers was born in Mineola, New York, and grew up in Farmingdale and then Rockville Centre, New York. His parents were James J. Silvers (1892–1986), a salesman, sometime farmer and small business owner, and Rose Roden Silvers (1895–1979), a music and arts columnist for The New York Globe, restaurateur, and one of the first female radio hosts for RCA.[2][3] He had one brother, Edwin D. Silvers (1927–2000), a civil engineer.[4][5] His paternal grandparents were Romanian Jewish immigrants, and his maternal grandparents were Russian Jews.[2][6] Silvers graduated from the University of Chicago with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1947 (at the age of 17) after completing an accelerated two-year program and attended Yale Law School for three semesters,[7][8] but left "disillusioned with the law".[9] Early career: 1950–1962Silvers worked as press secretary to Connecticut Governor Chester Bowles in 1950, who was campaigning for reelection.[10] During the Korean War he served in the U.S. Army, which sent him to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe Headquarters in Paris in 1952 as a speechwriter and press aide.[11] While in Paris, he attended the Sorbonne and Paris Institute of Political Studies (known as Sciences Po), eventually receiving its certificat de diplôme (diploma certificate).[12] His official duties left him time to work as an editor of a quarterly magazine published by the World Assembly of Youth and as a commissioning editor representing a small publishing company, Noonday Press.[7][13] In 1954, while working for Noonday, he met and befriended George Plimpton, editor of the new magazine The Paris Review, and after Silvers' discharge from the Army a few months later, Plimpton invited him to become managing editor.[12] Plimpton returned to the U.S. in 1955, leaving Silvers in charge;[13] living on a barge on the Seine with a friend, Silvers served as managing editor until 1956.[14] Plimpton later said that Silvers "made The Paris Review what it was".[12][15] Silvers continued his studies at the same time.[16] Silvers returned to New York in 1958,[10] becoming associate editor of Harper's Magazine, where he remained until 1963.[4] For an issue of the magazine in 1959 focusing on the state of writing in America, he engaged Elizabeth Hardwick to contribute her essay "The Decline of Book Reviewing", which fifty years later he described as "one of the most thrilling pieces I've ever published".[17] It became an inspiration for the founding of The New York Review of Books (NYRB).[1] In 1960, he edited the book Writing in America and translated La Gangrene, which describes the brutal torture of seven Algerian men by the Paris Security Police in 1958, shortly after Charles de Gaulle came to power.[18][19] New York ReviewDuring the 1962–63 New York City newspaper strike, when The New York Times and six other newspapers suspended publication, Hardwick, her husband Robert Lowell, and Jason and Barbara Epstein, saw an opportunity to introduce the sort of vigorous book review that Hardwick had imagined.[20] Jason Epstein knew that book publishers would advertise their books in the new publication, since they had no other outlet for promoting new books.[21] The group asked Silvers, who was still at Harper's, to edit the issue, and Silvers asked Barbara Epstein to co-edit it with him.[22][23] Silvers and Epstein "became an inseparable double act", editing The New York Review of Books together for the next 43 years, until her death in 2006.[2][24] Silvers continued as sole editor until his death in March 2017.[7][2] In later years, he described his motivation for continuing to edit the Review: "I feel it's a fantastic opportunity – because of the freedom of it, because of the sense that there are marvelous, intensely interesting, important questions that you have a chance to try to deal with in an interesting way. That's an extraordinary opportunity in life. And you'd be crazy not to try and make the most of it."[23] He said on another occasion: "We do what we want and don't try to figure out what the public wants."[19] Asked in 2007 about who might succeed him as editor, Silvers replied: "It's not a question that's posing itself."[25] Silvers also edited or co-edited several essay anthologies, including Writing in America (1960); A Middle East Reader: Selected Essays on the Middle East (1991); The First Anthology: Thirty Years of the New York Review (1993); Hidden Histories of Science (1995); India: A Mosaic (2000); Doing It: Five Performing Arts (2001), a collection of essays on the performing arts; The Legacy of Isaiah Berlin (2001); Striking Terror (2002); The Company They Kept (vol. 1, 2006; vol. 2, 2011); The Consequences to Come: American Power After Bush (2008); and The New York Review Abroad: Fifty Years of International Reportage (2013).[26] In 2009, he wrote the essay "Dilemmas eines Herausgebers" ("Dilemmas of an editor") appearing in the Austrian journal Transit – Europäische Revue.[27] He also served on the editorial committee of La Rivista dei Libri, the Italian-language edition of the Review,[28] until it closed in 2010.[29] Personal life and deathSilvers never married or had children.[2] He was linked romantically in the 1960s with Lady Caroline Blackwood.[30][31] For more than four decades from 1975 until her death, he lived with Grace, Countess of Dudley (1923–2016), widow of the 3rd Earl of Dudley,[10][32] with whom he shared a passion for opera.[4][23] Silvers commented that Dudley's "fineness of mind and spirit has been the center of my life".[15] A long-time vegetarian, Silvers "was struck by the essays of ... moral philosopher Peter Singer, who has written extensively about animal rights."[10][23] Silvers died on March 20, 2017, at the age of 87, at his Manhattan home after a short illness.[2][33] A memorial service was hosted by the New York Public Library in April 2017.[34] Silvers and Grace Dudley are buried together in Switzerland.[35] Reputation John Richardson wrote in a 2007 Vanity Fair article that "Jason Epstein's assessment of Silvers as 'The most brilliant editor of a magazine ever to have worked in this country' has been 'shared by virtually all of us who have been published by Robert Silvers'".[36] The British newspaper The Guardian called Silvers "the greatest literary editor there has ever been",[37] while Library of America remembered him as "an unsurpassed editor who helped define and sustain the literary and intellectual culture of New York and America".[38] The New York Times described him as "the voracious polymath, the obsessive perfectionist, the slightly unknowable bachelor-workaholic with the colossal Rolodexes and faintly British diction",[4] and, in his obituary, stated that "under his editorship [The Review] became one of the premier intellectual journals in the United States, a showcase for extended, thoughtful essays on literature and politics by eminent writers."[7] Author Louis Begley wrote, "the ideal editor of my – and I would guess every writer’s – dreams is ... Robert B. Silvers, the editor, brain, and heart of the NYRB. When I write a piece for his magazine, of course I have the immeasurable good luck to be edited by him. There is no experience quite like it. Bob knows everything that's worth knowing, a consequence of his unflagging curiosity."[39] "Bob's edits are scrupulous, comprehensive, and precise. They are frequently aimed at saving the reviewer's face."[40] Susan Sontag, a prolific contributor to the Review and a close friend of Silvers, called him a "fantastic, fanatical, brilliant" editor.[4] Roger Cohen wrote, after Silvers' death, "No eye for imprecise thought was ever more discerning; no edit a sharper yet gentler distillation than his. ... He was a stickler for accuracy. The pencil in his hand went to the heart of the matter."[41] In a 2012 profile of Silvers, The New York Times noted: "His greatest pleasure ... is simply good writing, which he talks about as others talk about fine wine or good food. Speaking about writers he likes, he sometimes flushes with enthusiasm. 'I admire great writers, people with marvelous and beautiful minds, and always hope they will do something special and revealing for us.'"[42] Philip Marino, in The University of Chicago Magazine, commented: "Like a chemist pairing ingredients to induce a specific reaction, Silvers has built his career matching the right author and subject, in hopes of generating an exciting and illuminating result. ... 'he puts a writer together with material that even the writer might not have thought was appropriate,' says Daniel Mendelsohn".[1] Glen Weldon, writing for NPR, concurred: "He encouraged writers to craft each review as a vigorous intellectual argument, and delighted in pairing reviewers with books that challenged their personal or political worldview."[33] Professor Peter Brown wrote: "Reviewing for Bob Silvers was like playing in the sprinkling rain of a mighty fountain ... to be doused in the sheer, bubbling delight of Bob’s own unquenchable enthusiasm and alert, discerning curiosity. It widened the heart".[43] In The Nation, Harvard professor Stanley Hoffmann observed that, in publishing some of the earliest criticisms of the Vietnam and Iraq wars, Silvers realized what other commentators missed: "In both instances, Bob Silvers was, in effect, whether deliberately or not, compensating for the weaknesses of the more established media. ... It was important that a journal which has the authority of the Review in a sense took up the slack and presented viewpoints which were extremely hard to get into the established media."[44] The Nation added, during the Iraq war:

Silvers said: "The great political issues of power and its abuses have always been natural questions for us".[42] His obituary in The New York Times commented that "Silvers made human rights and the need to check excessive state power his preoccupations, rising at times to the level of a crusade. ... [Silvers said], 'skepticism about government ... is a crucial point of view we have had from the first'."[7] In his 1974 book The American Intellectual Elite, Columbia University sociologist Charles Kadushin interviewed "the seventy most prestigious" American intellectuals of the late 1960s, including Silvers. The Time magazine review of the book expressed surprise at Silvers' position near the top of the list: "Robert Silvers, the editor of the New York Review of Books, the magazine that [Kadushin] indicates is favored by intellectuals who want to reach other intellectuals ... is an able editor but an infrequent writer; it must be assumed that his ranking at the top ... is due to a power not unlike that of the maître d' of an exclusive restaurant."[45] Adam Gopnik wrote that Silvers "raised the brow not just of American criticism – bringing elements of rigor, argument, and expansiveness to reviewing and reporting that remain intimidating to this day – but of American intellectual life."[46] Silvers had a reputation for hiring and developing assistants who later became prominent in journalism, academia and literature. In 2010, New York magazine featured several of these, including Jean Strouse, Deborah Eisenberg, Mark Danner and A. O. Scott.[47] Two of his former assistants, Gabriel Winslow-Yost and Emily Greenhouse, were appointed co-editors of the Review in 2019.[48] In 2011, Oliver Sacks identified Silvers as his "favorite New Yorker, living or dead, real or fictional", saying that the Review is "one of the great institutions of intellectual life here or anywhere."[49] Timothy Noah at Politico concluded that Silvers "made the New York Review the country’s best and most influential literary journal".[50] Work habits and editorial approachJonathan Miller said of Silvers' work habits: "He isn't just conscientious beyond the call of duty. He defines what duty is. You will often find him working until two in the morning in the office, with his little assistants from Harvard around him. He never stops. He's always meeting people, and talking".[12] Claire Messud wrote in 2012 that she was impressed, when submitting reviews for novels to the Review, that Silvers had "read the novel at hand, and sometimes with more sensitivity than I had ... he pointed out, delicately, that I'd attributed a quotation to the wrong character, and upon another occasion, that I'd summarized an event in a misleading way ... [but] Bob is unfailingly generous and kind, someone who carefully suggests rather than commands alteration. He is an extraordinary editor in part because he is always respectful, of even the least of his contributors, or the least contribution."[51] Charles Rosen elaborated:

A Financial Times interviewer, Emily Stokes, wrote in 2013 that Silvers viewed editing as "an instinct. You must choose writers carefully, having read all of their work, rather than being swayed by 'reputations that are, shall we say, overpromoted', and then anticipate their needs, sending them books and news articles" while seeking greater clarity, comprehensiveness and freshness in the writing.[10] Stokes commented that Silvers "radiates a genial warmth [but told her that] it is part of the editor's role ... not to be swayed by friendships with authors but to let reviewers express their genuine views."[10] Silvers described some of the diplomatic aspects of the job: "The act of reviewing can have a deep emotional effect. People get hurt and upset. You have to be aware of that, but you can't flinch. [You must also reject reviews] sometimes. You say, 'No, I'm terribly sorry, I can't visualise that in the paper. I don't think it's adequate to the subject.'"[16] James Atlas wrote of a typical day for Silvers: "In the late afternoon, he'd rush out to a lecture at the Council on Foreign Relations, show up at a dinner party, and then head back to the office to deal with the next breaking crisis."[52] Timothy Noah wrote: "Silvers edited three successive galleys for every piece, sharpening the argument, requesting additional evidence, removing pompous jargon and infelicitous phrases."[50] His New York Times obituary noted: "Silvers brought to [the Review] a self-effacing, almost priestly sense of devotion. ... [He was] loath to grant interviews. ... He arrived at the office early and left late, if at all, to the kind of heavyweight cocktail party that was, for him, a happy hunting ground for writers and ideas."[7] LegacyAt the time of his death, Silvers left the Review with a circulation of more than 130,000,[53] its book publishing operations, and a reputation as "the country’s best and most influential literary journal. ... It's hard to imagine that Hardwick ... would complain today that book reviewing is too polite."[50] The 50 Year Argument, a 2014 documentary film about the Review, co-directed by Martin Scorsese,[54] is "'[a]nchored by the old-world charm' of its editor, Robert Silvers".[55][56] Silvers appeared in other documentary films: Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself (2013),[57] Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold (2017)[58] and Oliver Sacks: His Own Life (2019).[59] In 2019, Silvers' estate created the Robert B. Silvers Foundation to support writers of in-depth political, social, economic, and scientific commentary, long-form arts and literary criticism, and intellectual essays. Daniel Mendelsohn is the foundation's director, and Rea Hederman is its president. It awards annual prizes, called the Silvers-Dudley Prizes, recognizing outstanding writing, including the Robert B. Silvers Prize for Journalism; the Robert B. Silvers Prize for Criticism; and the Grace Dudley Prize for Writing on European Culture. Prizes are in the amounts of $30,000 each for writers over 40, and $15,000 each for those under 40.[60][61] The first prizes were awarded in 2022.[62][63] Besides serving as a trustee of the New York Public Library, Silvers was "personally, and very discreetly, involved in the struggle to keep neighbourhood libraries open in the poorest precincts of New York."[2] The annual Robert B. Silvers lectures at the New York Public Library were established by Max Palevsky in 2002 and are given by experts in the fields of "literature, the arts, politics, economics, history, and the sciences."[64][65] The event has included lectures given by Joan Didion, J. M. Coetzee, Ian Buruma, Michael Kimmelman, Daniel Mendelsohn, Nicholas Kristof, Zadie Smith, Oliver Sacks, Derek Walcott, Mary Beard, Darryl Pinckney,[64] Lorrie Moore,[66] Joyce Carol Oates,[67] Helen Vendler,[68] Paul Krugman,[69] Masha Gessen,[70] Alma Guillermoprieto,[71] Mark Danner,[72] Sherrilyn Ifill,[73] and Justice Stephen Breyer.[74] Honors and awards On November 15, 2006, Silvers, together with Epstein, received the National Book Foundation Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community.[75] With Epstein, he also received in 2006 the Award for "Distinguished Service to the Arts" from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The National Book Critics Circle honored Silvers with the Ivan Sandrof Award for Lifetime Achievement in Publishing for 2011,[76] and in 2012, he was honored with the Hadada Prize by The Paris Review,[11][77] and a N.Y.C. Literary Honor for "contributions to literary life" in New York City.[78] At the N.Y.C. Literary Honors, readings were given, and, "in what may have been the most moving reading, [Silvers] excerpted architecture critic Martin Filler's rhapsodic review of the 9/11 Memorial designed by the young architect Michael Arad, which appeared in the NYRB last year."[79] In 2013, the French-American Foundation honored him with its Vergennes Achievement Award.[80] Also in 2013, he was awarded the 2012 National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama "for offering critical perspectives on writing. ... [H]e has invigorated our literature with cultural and political commentary and elevated the book review to a literary art form."[81] Among other honors, Silvers was a member of the executive board of the PEN American Center, the American Ditchley Foundation and the American Academy in Rome; he served as a trustee of the New York Public Library from 1997 and on the Paris Review Foundation. He was also a Chevalier of the French Légion d’honneur and a member of the French Ordre National du Mérite. In 1996, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[80][82] In 2007, Harvard University awarded him an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters,[83] and in 2013 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the British Academy.[84] In 2014, he received honorary Doctor of Letters degrees from both the University of Oxford and Columbia University.[85][86] Silvers was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Century Association.[80][87] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||