|

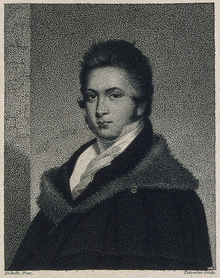

Richard Harlan

Richard Harlan (September 19, 1796 – September 30, 1843) was an American paleontologist, anatomist, and physician. He was the first American to devote significant time and attention to vertebrate paleontology and was one of the most important contributors to the field in the early nineteenth century. His work was noted for its focus on objective descriptions, taxonomy and nomenclature. He was the first American to routinely apply binomial Linnaean names to vertebrate and invertebrate fossils.[1][2] Prior to the time of Harlan, it was common practice to publish only a genus name for a fossil animal that was new to science.[3] BiographyHarlan was born in Philadelphia on September 19, 1796, to Joshua Harlan, a wealthy Quaker merchant, and his wife Sarah Hinchman Harlan, one of their ten children. He was three years older than his brother Josiah Harlan, who would become the first American to visit Afghanistan. Harlan graduated in medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in 1818 after taking time off during his studies to spend a year sailing to India as a ship's surgeon for the British East India Company. He worked briefly at the private medical school of Joseph Parish. He wrote a text on the human brain Anatomical Investigations (1824).[4] In 1820, he was a physician at the Philadelphia Dispensary, where he worked with Philip Syng Physick. In 1822 he was elected professor of comparative anatomy at Charles Wilson Peale's Philadelphia Museum. One of his passions was the collection and study of human skulls. In 1822, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society.[5] At its peak, his collection contained 275 skulls, the largest such collection in America.[6] In 1825 he published Fauna Americana, a catalogue of American mammals, including those known only from fossils.[2] In 1832 he went to Montreal to study a cholera epidemic. Harlan also collected and received natural history specimens from a number of his friends and colleagues including Dr William Blanding (1773-1857), Samuel George Morton (1799-1851), and Samuel Wilson (and his son). He collaborated with other naturalists and supported Audubon during his travels. He described a number of species including Macroclemys temminckii, Harlan's ground sloth, Harlan's muskox and the Indian Hoolock gibbon. A parasite of the alligator snapping turtle is named after him Eimeria harlani.[7][8][9] In 1833 he attended a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science where he presented information on the fossil reptiles of America. He made an error in describing a species called Osteopera platycephala based on the skull of Agouti paca. He was criticized by his colleague from the Peale museum, John D. Godman (1794-1830), who wrote anonymously. In 1834, Harlan described and named Basilosaurus ("king lizard"), a genus of early whale, erroneously assuming he had found a Plesiosaurus-like dinosaur.[10] In 1839 he visited Europe again and received a plaster copy of Mosasaurus hoffmannii from the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle that is now in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. While in France he received news of a fire that had destroyed his collections. In 1842 he moved to New Orleans, Louisiana where he died of apoplexy a year later.[11] WorksHarlan was the author of several books including:

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||