|

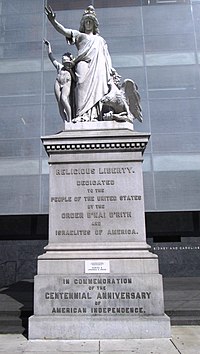

Religious Liberty (Ezekiel)

Religious Liberty was commissioned by B'nai B'rith and dedicated "to the people of the United States" as an expression of support for the Constitutional guarantee of religious freedom. It was created by Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a B'nai B'rith member and the first American Jewish sculptor to gain international prominence. The statue was 11 feet (3.4 m) high, of marble, and the plinth (base) added another 14 feet (4.3 m). It weighed 26,000 pounds (12,000 kg), and was said to be the largest sculpture created in the 19th century.[1] It was carved in Italy and shipped to Fairmount Park in Philadelphia for the nation's 1876 Centennial Exposition. It was later moved to Independence Mall and now (2023) stands in front of the National Museum of American Jewish History.  The meaning of the sculpture

Creation of the sculptureIn his Memoirs, Ezekiel described how the block of marble occupied two freight cars, and took twenty men "several days" to move it from the railway station to his studio, the iron chain of a derrick having snapped. "A great deal of street paving" was necessary afterwards, to repair the damage. He had to knock down part of a wall to get it in his studio, and break it down again to get it out.[2]: 187–190 When it was completed, which took two teams of stonecutters, one working during the day and one at night, for one day he invited the Roman public to see it. He wrote that it made him famous overnight; one newspaper said that it "was perhaps the most important work of art that had been produced in centuries."[2]: 190 It led to Ezekiel's introduction to Giuseppe Garibaldi.[2]: 188 Financial problemsThe commission was for $20,000 (equivalent to $572,250 in 2023).[1] According to Ezekiel, before obtaining the marble a letter from B'nai Brith informed him that they were unable to raise the money to pay him, and he should abandon the project.[2]: 187 Nevertheless, having created the clay model, and this being the first ever Jewish commission for a sculpture, with a guaranteed place at the Centennial Exposition, he decided to continue work. He had to borrow money to pay for its transportation to Philadelphia himself. He did not receive payment until three years afterward, and when the loans and interest had been paid there was nothing left for him.[2]: 192 Documents concerning the commission are held in the B'nai B'rith archives. A program from the ceremonial unveiling is held by the National Museum of American Jewish History.[3] References

|

||||||||||||||||||