|

Reign of Isabella II

The reign of Isabella II has been seen as being essential to the modern history of Spain. Isabella's reign spanned the death of Ferdinand VII in 1833 until the Spanish Glorious Revolution of 1868, which forced the Queen into exile and established a liberal state in Spain.[1] After the death of Ferdinand VII on 29 September 1833, his wife Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies assumed the regency with the support of the liberals, on behalf of their daughter Isabella. Conflict with her brother-in-law, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, who aspired to the throne by virtue of a supposedly valid Salic Law – already repealed by Carlos IV and Ferdinand VII himself – led the country into the First Carlist War.[2] After the brief regency of Espartero, which succeeded the regency of María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias, Isabella II was proclaimed of age at the age of thirteen by resolution of the Cortes Generales[3] in 1843. Thus began the effective reign of Isabella II, which is usually divided into four periods: the moderate decade (1844–1854); the progressive biennium (1854–1856); the period of the Liberal Union governments (1856–1863) and the final crisis (1863–1868).[citation needed] The reign of Isabella II was characterized by an attempt to modernize Spain which was contained, by the internal tensions of the liberals, the pressure that continued to be exerted by the supporters of more or less moderate absolutism, the governments totally influenced by the military establishment and the final failure in the face of the economic difficulties and the decline of the Liberal Union which led Spain into the experience of the Democratic Sexenio. Her reign was greatly influenced by the personality of Queen Isabella, who had no gifts for government and was under constant pressure from the Court, especially from her own mother, and also from Generals Ramón María Narváez, Baldomero Espartero and Leopoldo O'Donnell, which prevented the transition from the Old Regime to the Liberal State from being consolidated, and Spain reached the last third of the 19th century in unfavorable conditions compared to other European powers.[4] The reign of Isabella II was divided into two major stages:

Regencies of María Cristina and EsparteroThe Regency of María Cristina de Borbón was marked by the civil war arising from the succession dispute between the supporters of the future Isabel II or "Isabelinos" (or "Cristinos" after the name of the regent) and those of Carlos María Isidro or "Carlists". Francisco Cea Bermúdez, who was very close to the absolutist theses of the late Ferdinand VII, was the first President of the Council of Ministers. The absence of liberal gains forced the departure of Cea and the arrival of Martínez de la Rosa, who convinced the Regent to enact the Royal Statute of 1834, a charter that did not recognize national sovereignty, which was a step backwards, compared to the Constitution of Cadiz of 1812, granted by Ferdinand VII.[2]  The failure of the conservative or "moderate" liberals brought the progressive liberals to power in the summer of 1835. The most prominent figure of this period was Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, a politician and financier of great prestige who institutionalized the "revolutionary juntas" that had arisen during the liberal revolts of the summer and initiated several economic and political reforms, including the confiscation of the property of the regular orders of the Catholic Church. During the second progressive government presided over by José María Calatrava and with Mendizábal as the strong man in the Treasury portfolio, the new Constitution of 1837 was approved in an attempt to combine the spirit of the Cadiz Constitution and achieve consensus between the two main liberal parties, moderates and progressives. The Carlist War caused serious economic and political problems. The fight against the army of the Carlist Tomás de Zumalacárregui, who had been in arms since 1833, forced the Regent to place a large part of her trust in the Christian military, who achieved great renown among the population. One of these was General Espartero, who was responsible for certifying the final victory in the Oñate Agreement, better known as the Abrazo de Vergara (the embrace of Vergara). In 1840, María Cristina, aware of her weakness, tried to reach an agreement with Espartero, but he sided with the progressives when the "revolution of 1840" broke out in Madrid on 1 September. María Cristina was then forced to leave Spain and leave the regency in Espartero's hands on 12 October 1840. During Espartero's regency, the general did not know how to surround himself with the liberal spirit that had brought him to power and preferred to entrust the most important and transcendental matters to like-minded military officers, known as Ayacuchos because of the false belief that Espartero had been at the Battle of Ayacucho. In fact, General Espartero was accused of exercising the Regency in the form of a dictatorship. For their part, the conservatives represented by O'Donnell and Narváez did not cease their pronouncements. In 1843 the political deterioration worsened and even the liberals who had supported him three years earlier were conspiring against him. On 11 June 1843 the revolt of the moderates was also backed by Espartero's trusted men, such as Joaquín María López and Salustiano Olózaga, which forced the general to abandon power and go into exile in London. The effective reign of Isabella IIWith the fall of Espartero, the political and military class as a whole came to the conviction that a new regency should not be called for, but that the Queen's majority should be recognized, despite the fact that Isabella was only twelve years old. Thus began the effective reign of Isabella II (1843–1868), which was a very complex period, not without its ups and downs, which marked the rest of the political situation of the 19th century and part of the 20th century in Spain.[1][2] The proclamation of the coming of age of Isabella II and the "Olózaga incident" produced a political vacuum. The "radical" progressive Joaquín María López was restored by the Cortes to the post of Head of Government on 23 July, and to do away with the Senate, where the "Esparteristas" had a majority, he dissolved it and called elections to renew it completely – in violation of Article 19 of the 1837 Constitution, which only allowed it to be renewed by thirds. He also appointed the City Council and the Diputación de Madrid – which was also a violation of the Constitution- to prevent the "Spartacists" from taking over both institutions in an election —López justified it as follows: "when fighting for existence, the principle of conservation is the one that stands out above all: one does what one does with the sick person who is amputated so that he may live".[1] In September 1843 elections to the Cortes were held in which progressives and moderates stood in coalition in what was called a "parliamentary party", but the moderates won more seats than the progressives, who were also still divided between "temperates" and "radicals" and thus lacked a single leadership. The Cortes approved that Isabella II would be proclaimed of age in advance as soon as she reached the age of 13 the following month. On 10 November 1843 she swore in the Constitution of 1837 and then, in accordance with parliamentary custom, the government of José María López resigned. The task of forming a government was given to Salustiano de Olózaga, the leader of the "temperate" sector of progressivism. He was chosen by the queen because he had made an agreement with María Cristina on his return from exile.[2] The first setback suffered by the new government was that its candidate to preside over the Congress of Deputies, the former Prime Minister Joaquín María López, was defeated by the Moderate Party candidate Pedro José Pidal, who not only received the votes of his party but also those of the "radical" sector of the progressives headed at the time by Pascual Madoz and Fermín Caballero, who were joined by the "temperate" Manuel Cortina. When the second difficulty arose, to push through the Law on Town Councils, Olózaga appealed to the queen to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections that would provide him with a supportive House, instead of resigning because he had lost the confidence of the Cortes. It was then that the "Olózaga incident" occurred, which shook political life as the president of the government was accused by the moderates of having forced the queen to sign the decrees of dissolution and calling of the Cortes. Olózaga, despite proclaiming his innocence, had no choice but to resign and the new president was the moderate Luis González Bravo, who called elections for January 1844 with the agreement of the progressives, despite the fact that the government had just come to power and had reinstated the 1840 Law on Town Councils – which had given rise to the progressive "revolution of 1840" that ended with the regency of María Cristina de Borbón and the assumption of power by General Espartero.[2] As for the "Olózaga incident", the new President of the Council of Ministers, González Bravo, who had taken office on 1 December, proposed discussing it in the Chamber. During the sessions Olózaga demonstrated the falsity of the accusations, but the parliamentary majority enjoyed by the moderates after the elections enabled him to win the vote, and Olózaga left for England, not so much because of a banishment that had not been ordered, but out of fear for his own life, which was threatened in Madrid. In some parts of the country, the political direction the Kingdom was taking was viewed with suspicion, which led to some rebellions, such as the Boné Rebellion led by Pantaleón Boné, who took control of the city of Alicante for more than 40 days with the intention of extending his revolution to other cities. González Bravo carried out a kind of "civil dictatorship", which would last 6 months, and during which he restored the Law of Town Councils to put an end to the Juntas, and put an end to the National Militia by creating the Civil Guard.[5] The January 1844 elections were won by the moderates, which provoked progressive uprisings in several provinces in February and March that denounced the government's "influence" on the outcome of the elections. Thus the progressive leaders Cortina, Madoz and Caballero were imprisoned for six months -Olózaga was not arrested because he was in Lisbon and Joaquín María López remained in hiding until his companions were released from prison-. In May General Ramón María Narváez, the true leader of the Moderate Party, assumed the presidency of the government, inaugurating the so-called moderate decade (1844–1854).[5] After the fall of Espartero and the proclamation of Isabella's majority, a series of moderate governments began, supported by the Crown. The first measure taken by the moderates in power was to prevent progressive uprisings, for which they disbanded the National Militia and re-established the Law of Town Councils to better control local governments from the central government, which prevented the creation of Juntas. When her reign began, the Queen was only 13 years old and had no experience of government, so she was greatly influenced by the people around her. The Moderate DecadeIn the spring of 1844, the country was considered to have been pacified, which meant that the civil dictatorship of González Bravo came to an end and new elections were called, in which Narváez won. This was a complicated situation for him, as he had not shown great political skills. He ran a very authoritarian government, treating the ministers as his subordinates in the army. Narváez took a step forward in political reforms, going as far as the construction of a centralized state and fiscal reform. His ministerial team included Alejandro Mon, Minister of Finance, in charge of tax reform; Pedro José Pidal, Minister of the Interior, in charge of creating the centralized state and the concordat with the Church in 1851; and Francisco Martínez de la Rosa, Minister of State and creator of the policy of the just average. The Moderate Decade began with the presidency of the leader of the Moderate Party, General Narváez, who took office on 4 May 1844. The Moderate Party held exclusive power thanks to the support of the Crown, without the progressives having the slightest chance of gaining access to government.   With the Moderate Party firmly in government, 1845 was a crucial year for Spanish liberalism, as it was a crossroads at which the Moderate Party took stock of its achievements and failures since the Liberal Revolution. According to the government, it was time to see what could be maintained and what had to be changed. According to Narváez, if the revolutionary cycle came to an end in 1845, a number of problems would have to be addressed, such as the Carlists, unhappy at the failure to fulfill the agreement with Espartero; the situation of the Church, which had lost much of its heritage and above all its influence; and political problems, known as "constitutional instability", because two constitutions had been drawn up in less than five years. The solution found by the moderates was to draw up a new constitution, that of 1845. Several drafts of a new Constitution were presented, including that of the Marquis of Maluma, which followed the line of a charter that gave all power to the Crown, and was therefore rejected outright. The progressives could not oppose Narváez because they had no presence in the Cortes, so the doctrinaire liberal model was established, which would establish a constitutional monarchy with sovereignty shared between the Crown and the Cortes. In terms of the declaration of rights, the 1845 Constitution was notable for its laws on printing and religion. There was no prior censorship of printing, but special courts were created to try crimes of insult against the government or the Crown. With regard to religion, the freedom of worship of 1837 was rejected, although it did not reach the intolerance of the Cadiz Constitution of 1812. In 1845 Spain became a confessional state and the subsidy for worship and the clergy was re-established, as well as favoring the presence of the Church in education, which served as the first step towards reconciliation between Church and State, which would come in 1851 with the Concordat. With regard to the organization of the powers of the State, the 1845 Constitution established a bicameral model, Senate and Congress, renewed every five years and whose representatives were elected by means of the law of single-member districts (in each district there was only one winner) to achieve very stable parliamentary majorities. In addition, the rents to be elected (12,000 reals) and to vote (400 reals) are established. In 1846 only 0.8% of the population, almost 100,000 people, voted. During this period of complete moderate rule, the latter tried to reverse the liberal advances of the previous stages, imposing a new municipal law (8 January 1845) with direct census suffrage, reinforcing centralism and approving a new constitution, that of 1845, which returned to the model of shared sovereignty between the King and the Cortes and reinforced the powers of the Crown. On the legislative level, various Organic laws were passed that accentuated the centralization of public administration by controlling the political power of the Town councils and universities, in a clear attempt to limit their powers as they were heavily influenced by the liberals. The division of the Moderate Party soon emerged, which contributed to the political instability that manifested itself in the continuous changes in the presidency of the government, beginning with the dismissal of Narváez on 11 February 1846, associated with the conflictive marriage that was arranged for the Queen. In fact, that year she was to marry Francisco de Asís de Borbón, her cousin, on 10 October. Earlier, the Queen's mother, the former Regent Maria Cristina, had hatched a marriage plan to marry her daughter to the heir to the French crown. Such plans aroused the suspicions of England, which at all costs wanted the Treaty of Utrecht to be respected and to prevent the two nations from being united under a single king. After the Accords of Europe, the number of candidates for Elizabeth was limited to just over six, from which Francis of Assisi was finally chosen. Francisco Javier de Istúriz's government managed to hold on until 28 January 1847, when a struggle for control of the Cortes with Mendizábal and Olózaga, who had returned from exile after the Queen's personal authorization, forced him to resign. From January to October of that year three governments succeeded one another without direction while the Carlists continued to stir up trouble and some liberal émigrés returned from exile. On 4 October Narváez was reappointed President, who appointed the conservative Bravo Murillo as his right-hand man and Minister of Public Works. The new government was stable in principle until the Revolution of 1848, which swept through Europe, led by the workers' movement and the more liberal bourgeoisie, provoked insurrections in the interior of Spain, which were harshly repressed; in addition, diplomatic relations with Great Britain were broken off, as it was considered to be a participant in and instigator of the Carlist movements in the so-called Matiners' War. Narváez acted as a true dictator, confronting the Queen, the King consort, the liberals and the absolutists. The confrontation lasted until 10 January 1851, when he was forced to resign and was replaced by Bravo Murillo. Once in power, Bravo Murillo tried to appease the confrontation with the Holy See as a result of the disentailment processes carried out by Mendizábal in the previous period by signing a Concordat in 1851 with Pope Pius IX, the second in the history of Spain, which, in short, established a policy of protection for the assets of the Catholic Church against possible new disentailment processes, especially civil ones; The sale of those still in the hands of the State was halted and the Church received financial compensation. In its first article, the Concordat established:

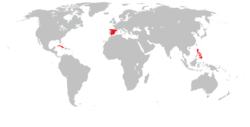

In December 1851, Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon III, staged a coup d'état in France. This had repercussions in Spain, where Bravo Murillo suspended the Cortes and closed them for a year. With the Cortes closed, he ruled by decree and tried to implement a political system that would give more rights to the Crown. This reform caused a political reaction, and in May 1852 a letter was written to the Queen asking her to reopen the Cortes. In December 1852, they were reopened, and a new president was appointed: Francisco Martínez de la Rosa. Bravo Murillo, still president, was against it, so he dissolved the Cortes and drafted a constitutional project in 1852, with an absolutist slant to eliminate the liberal character that he believed the 1845 Constitution had, but it was unpopular and rejected. He also published new organic laws to regulate the functioning of the future Cortes. Bravo Murillo failed and was forced to resign, although one of his reforms did become law in 1857: that of hereditary, ex officio and life senators. These political events led to an armed conflict based on the Crown's support for an extreme policy that threatened a return to the liberalism of 1834. A group of some 200 senators and congressmen tried to find a political solution, but they received no response and in February 1854 an uprising was suppressed in Saragossa, although the conspiracy continued, led by Narvaecists and Puritans. The next uprising took place in Vicálvaro, "La Vicalvarada", with O'Donnell and Dulce, who did not achieve much success at first, something that changed in Manzanares (Ciudad Real), where they were joined by General Serrano. Together they starred in the Manzanares Manifesto, which provoked a major political change and uprisings in Barcelona, Valladolid and Valencia until the government cabinet resigned and a Junta de Gobierno was created in Madrid, forcing the Queen to appoint a new government. Surprisingly, the queen appoints Espartero as head of government and not O'Donnell, who is appointed Minister of War. The Progressive Biennium (1854–1856)During Bravo Murillo's conservative government, a high degree of corruption was evident as a result of disorderly economic growth and internal intrigues to obtain advantages in public concessions, a situation in which the entire royal family itself was implicated. Bravo Murillo, who many considered an honest public servant, resigned in 1852, and was succeeded by three governments until July 1854. Meanwhile, Leopoldo O'Donnell, a former collaborator of the former Regent María Cristina, joined the more liberal moderates and tried to organise an uprising, relying on a number of officers and some of the figures who, years later, would become prominent politicians such as Antonio Cánovas del Castillo. On 28 June O'Donnell, who had gone into hiding in Madrid, joined forces and clashed with troops loyal to the government at Vicálvaro, in what became known as La Vicalvarada, but there was no clear winner. Throughout June and July other troops joined the uprising in Barcelona. On 17 July, in Madrid, civilians and soldiers took to the streets in a succession of violent acts, endangering the very life of the queen's mother, María Cristina, who had to seek refuge. The barricades and the distribution of weapons gave victory to the insurgents. After some desperate attempts by the queen to appoint a president of the council to contain the riots, she finally surrendered to the evidence and, following her mother's orders, appointed Espartero as president. This marked the beginning of the so-called progressive biennium. On 28 July 1854, Espartero and O'Donnell entered Madrid, acclaimed by the crowd as heroes. Espartero was forced to appoint O'Donnell as minister of war because of his popularity and the control he exercised over large sections of the military. This communion between the two, seemingly loyal to each other, was not without its problems. While O'Donnell tried to counteract Espartero's progressive liberal practices in terms of his position on the Church and disentailment, the former regent sought a path towards liberalism in Spain, greatly influenced by his own personality and the changes taking place in Europe. The biennium was therefore a period marked by a coalition between more "left-wing" moderates and more "right-wing" progressives, in which progressive laws were reinstated, such as the law on town councils and the Militia, and a new constitution was drawn up, but it was never promulgated. The main legislative work of the Biennium was the economic reforms, aimed at consolidating the middle class. Among the economic measures were Madoz's disentailment and the railway law. The new confiscation affected the assets of the local councils and, to a lesser extent, the Church, military orders and some charitable institutions. The number of nationalised assets was much greater than in 1837. The objectives were to clean up the treasury and pay for the construction of the railway. This confiscation had serious consequences: for the town councils, losing land meant losing one of their main means of financing. The Railway Law was published in 1855 to regulate the construction of the railway network and to seek investors for its development. There were no major investors in Spain, so the capital was foreign. In addition, the infrastructure and trains were English, which did not favor Spanish iron and steel industries. Moreover, the track gauge was different from the European one; the railway would not become the business it was expected to be. On the other hand, social unrest increased, as in the uprising in Barcelona against forced conscription, low wages and long working hours. The government reacted by introducing some labour improvements and the right of association. The final crisis came in 1856, with numerous uprisings that forced Espartero to resign. The queen appointed O'Donnell as head of government. The experience of the biennium came to an end when the break between the two "swordsmen", Generals Espartero and O'Donnell, was consummated. O'Donnell had been working on the Liberal Union while he lived with Espartero in the government. The 1854 elections to the Constituent Cortes themselves gave a greater number of seats to the supporters of the former than to the latter. It is not surprising, therefore, that attempts at coexistence collapsed at the time of Madoz's disentailment and the religious question, when a bill was presented to the Cortes declaring that no one could be disturbed because of their beliefs. The proposal was approved and relations with the Holy See were broken off, and the Concordat of 1851 fell. But O'Donnell was not prepared to allow this situation to continue. Espartero, aware of the situation, activated his resources in defence of liberalism by mobilising the National Militia and the press against the moderate ministers, but the Queen preferred to grant O'Donnell the premiership in such an unstable situation, which was compounded by the Carlist uprisings in Valencia and a serious economic situation. The two sides clashed in military actions in the streets on 14 and 15 July 1856, where Espartero preferred to withdraw. The moderate biennium and the governments of the Liberal Union (1856–1863) Once appointed President of the Council of Ministers, O'Donnell restored the 1845 Constitution with an Additional Act with which he tried to attract liberal sectors. The struggles between the different moderate and liberal factions, and among themselves, continued in spite of everything. After the events of July, O'Donnell's weakness led the queen to change government again with Narváez on 12 October 1856. The instability continued and the queen offered the presidency to Bravo Murillo, who refused and General Francisco Armero took over the post for less than three months. On 14 January 1858 he was succeeded by Francisco Javier Istúriz. O'Donnell's return would mark the beginning of the long period of the Liberal Union governments. On 30 June 1858, O'Donnell formed a government in which he reserved for himself the Ministry of War. The cabinet lasted four and a half years, until 17 January 1863, and was the most stable government of the period. Although there were occasional changes, it had no more than a dozen ministers. The key members of the new executive were the minister of Finance, Pedro Salaverría, who was in charge of maintaining the economic recovery, and the minister of the interior, José de Posada Herrera, who masterfully and skillfully controlled the electoral lists and any misbehavior of the members of the new Liberal Union party. The 1845 constitution was re-established and the elections to the Cortes on 20 September 1858 gave the Liberal Union absolute control of the legislative branch. The most important actions were the major investments in public works, including the approval of extraordinary credits, which allowed the development of the railways and the improvement of the army; the policy of confiscation continued, although the State handed over public debt to the Church in exchange and reinstated the Concordat of 1851; various laws were passed that would later be key and whose validity extended into the 20th century: the Mortgage Law (1861), internal administrative reform of the Central Administration and the municipalities and the first Road Plan. To its detriment, the government did not manage to banish the political and economic corruption that reached all levels of power, did not approve the announced press law and, from 1861 onwards, saw its parliamentary support wane. Carlist uprisings and peasantsIn 1860 there was the Carlist landing at San Carlos de la Rápita, led by the pretender to the throne Carlos Luis de Borbón y Braganza in an attempt to land the equivalent of a regiment of loyalists from the Balearic Islands near Tarragona to start a new Carlist war, which ended in a resounding failure. There was also the Peasant Uprising of Loja led by the veterinarian Rafael Pérez del Álamo, the first major peasant movement in defence of land and work, which was repressed and crushed in a short time with several death sentences. Foreign policyIn foreign policy, during the governments of the Liberal Union, the so-called "prestige" or "patriotic exaltation" actions took place, which had broad popular support, such as the Franco-Spanish Expedition to Cochinchina from 1857 to 1862; participation in the Crimean War; the African War of 1859, in which O'Donnell obtained great popular support and prestige by consolidating the positions of Ceuta and Melilla, but was unable to obtain Tangiers due to British pressure; the Anglo-French-Spanish expedition to Mexico; the annexation of Santo Domingo in 1861; and the questionable, and unnecessary, First Pacific War in 1863. These foreign policy actions were an attempt to halt Spain's decline as a colonial power, which had occurred after the independence of the South American countries and the defeat at Trafalgar, while its role in Europe had diminished considerably. Meanwhile, France and Britain had occupied the European space and their respective empires were active in America, Asia and Africa. In principle, the foreign policy of the Elizabethan era tried to limit itself to maintaining Spain's status as a second-rate power, but this was limited in several ways. Firstly, the lack of definition of Spanish international action, even during the governments of the Liberal Union; secondly, the maintenance of economic interests in different parts of the world which, however, could not be met by a modern army capable of meeting the challenges of moving around the globe; thirdly, the queen's own ineffectiveness and lack of knowledge of international policy; and fourthly, the military and economic strength of France and Great Britain. As for the European context, the European landscape had changed. On the one hand, Britain and France, far from clashing as in the past, had allied, helping Elizabeth II to hold on to the throne. Prussia, Austria and Russia were supporters of the Carlists, to whom they lent their more or less veiled support. In these circumstances, Spain joined the Quadruple Alliance of 1834 along with Portugal under simple premises: France and Britain supported the Elizabethan monarchy as long as it maintained an agreed foreign policy with both, although when the two great powers held different positions, Spain could defend its own position. The fall of the Liberal Union governmentIn 1861 the policy of harassment of O'Donnell's government multiplied on the part of the Moderate and Progressive parties. Influential people such as Cánovas, Antonio de los Ríos Rosas -one of its founders- and General Juan Prim himself, among others, left the Liberal Union due to disagreements with the cabinet. The most common complaint was the betrayal of the ideas that had brought the prestigious general to power. They were joined by members of the army and the Catalan bourgeoisie. The discrepancies in the cabinet were not resolved with the departure of Posada Herrera in January 1863. Thus, on 2 March the queen accepted O'Donnell's resignation. Final crisis of the reign (1863–1868)After the progressive biennium, the constitution of 1845 was re-established and the Liberal Union remained in power under O'Donnell (1856–1863).[6] Narváez returned, in a quiet period, with the establishment of the centralised state order and after halting the disentailment process of Madoz. Foreign policy was used to prevent the population from focusing on internal problems. Spain became involved in conflicts in Morocco, Indochina and Mexico. In 1863, the coalition of progressives, democrats and republicans won, although Narváez came to power, with a dictatorial government that ended in 1868, when a new revolution broke out, directed against the government and Queen Isabella II: the Glorious Revolution.[7] Replacing O'Donnell was not easy. The traditional parties had more than their share of problems and clashes between their members. It was the Moderates, through General Fernando Fernández de Córdova, who offered the possibility of forming a cabinet. The progressives, led by Pascual, considered it advisable to dissolve the Cortes. In the end, the queen entrusted the government to Manuel Pando Fernández de Pineda, Count of Miraflores, who had little support, and although he tried to involve the progressives in the political game, they decided to withdraw. His presidency lasted only until January 1864. Seven other governments succeeded one another until the revolution of 1868, including the one presided over by Alejandro Mon y Menéndez on 1 March 1864, which included Cánovas as Minister of the Interior for the first time and Salaverría as Minister of Finance. For their part, the progressives considered Espartero to have been defeated, and Olózaga, together with Prim, began to form an alternative that had no confidence in Isabella II's ability to overcome the permanent crisis. Narváez formed a government on 16 September 1864 with the intention of uniting forces and bringing together a unionist spirit that would allow the progressives to integrate into active politics, fearful that the questioning of the reign would go further. The progressive refusal to participate in a system they considered corrupt and outdated led Narváez to authoritarianism and a cascade of resignations within the cabinet. To all this was added, to the discredit of the government, the events of the Night of St. Daniel on 10 April 1865. University students in the capital were protesting against the measures of Antonio Alcalá Galiano, who tried to remove the spirit of rationalism and Krausism from the classrooms, maintaining the old doctrine of the official morality of the Catholic Church, and against the expulsion of Emilio Castelar from the chair of history for his articles in La Democracia, where he denounced the sale of the Royal Heritage with the queen's appropriation of 25% of the revenue. Harsh government repression of the protests led to the deaths of thirteen university students. The crisis led to the formation of a new government on 21 June with the return of O'Donnell, Cánovas and Manuel Alonso Martínez to the ministry of finance, as well as other prominent figures. Among other measures, a new law was passed which increased the electoral body to 400,000 voters, almost double the previous number, and elections to the Cortes were called. Before the elections were held, however, the progressives announced that they were maintaining their withdrawal. Prim revolted in Villarejo de Salvanés in a clear political turn that was committed to seizing power by force, but the coup was not properly planned and failed. Once again, the hostile attitude of the progressives enervated O'Donnell, who reinforced the authoritarian content of the government, which led to the uprising at the San Gil Barracks on 22 June, again organised by Prim, but which again failed and filled the streets with blood, with more than sixty people condemned to death. O'Donnell retired, exhausted, from political life and on 10 July he was replaced by Narváez, who condoned the unexecuted sentences of the rebels but maintained the authoritarian rigour with expulsions of republicans and Krausists from the professorships and the strengthening of censorship and public order. When Narváez died, he was succeeded on 23 April 1868 by the authoritarian Luis González Bravo, but the revolution had been forged and the end of the monarchy approached on 19 September with La Gloriosa to the cry of "Down with the Bourbons! Long live Spain with honour!", while Isabella II went into exile to begin the democratic period. The creation of the centralized stateThe centralized state represents the great contribution of the Moderates, above all because of its duration, because it is in force until the State of the Autonomies. The centralised state was not part of the constitution of 1845, but was created by organic laws. The architect was Pedro José Pidal, who imported the Napoleonic model of centralisation carried out during the consulate. According to Napoleon, centralism consisted of creating an administration controlled by single-person agents. The most important link was the central government, followed by the departments, headed by prefects, and below that was the maire at the head of each basic territorial unit. Adapted to Spain, the queen and the head of government are placed first. In the second tier are the civil governors, at the head of the provinces and appointed by the central government; and finally the mayors, town councils and deputations, appointed by the civil governors, although in large cities they are appointed by the central government. Within the centralised Spanish state, the provincial councils, which had had great political and economic power, stood out, but with the Moderates their power was reduced to a consultative body. The main support of each civil governor was the provincial council, appointed from Madrid, which acted as a court for contentious and administrative matters, mediating between citizens and the administration. Within the town councils, all councillors are elected by census suffrage and must be accepted by the mayor and the civil governor. The mayor must maintain public order, adapting to what is designated by the central government, which, in some cases, reserves the right to appoint a Corregidor instead of a mayor, given that the mayor was elected by election and the Corregidor was handpicked. Bibliography

References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||