|

Regiment of Riflemen

The Regiment of Riflemen was a unit of the U.S. Army in the early nineteenth century. Unlike the regular US line infantry units with muskets and bright blue and white uniforms, this regiment was focused on specialist light infantry tactics, and were accordingly issued rifles and dark green and black uniforms to take better advantage of cover. This was the first U.S. rifleman formation since the end of the American Revolutionary War 25 years earlier.[1]

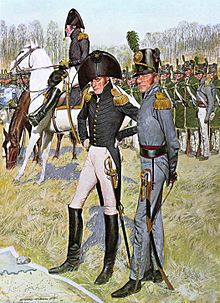

The regiment was first activated in 1808. During the War of 1812, it was temporarily designated as the 1st Regiment of Riflemen when the War Department created three additional similar regiments. The regiment never fought as a unit. Companies, detachment from companies or collections of companies were stationed at a distance from each other and were often allocated to other commands. After the War, the other three regiments were inactivated and the regiment reverted to its unnumbered designation. The regiment was inactivated in June 1821. BackgroundOn April 12, 1808, following the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, the U.S. Congress passed legislation authorizing an increase in the size of the U.S. Army, to include a regiment of riflemen.[2]: 12 [3]: 141 OrganizationThe headquarters of the regiment was authorized one colonel, one lieutenant colonel, one major, and administrative and support officers.[2]: 12 The winter uniform of the regiment was green jackets with black collars and cuffs; the summer uniform was green hunting shirts and pantaloons with buff fringe.[4] : 111 In 1814, uniform regulations specified gray cloth.[5]: 9 Companies were raised in various jurisdictions: three in New York and Vermont; three in the Louisiana and Mississippi Territories; and four in Ohio, Kentucky, and the Indiana Territory. Each company had an authorized strength of 84, including 68 privates; companies rarely attained their authorized strength.[5]: 1 Regimental depots were placed in Shepherdstown, Virginia, and Savannah, Georgia.[2]: 12 On February 10, 1814, an act of Congress raised an additional three regiments of riflemen. The Regiment of Riflemen was subsequently redesignated as the 1st Regiment of Riflemen while the additional three were designated as the 2nd, 3rd and 4th regiments.[3]: 141 Nevertheless, the four regiments were consolidated again on March 3, 1815, by a further act of Congress. As a result, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Regiments of Riflemen were disbanded and the 1st reverted to its unnumbered designation.[3]: 141  Service in the Pre-warNew OrleansBy 1810, over half of the regiment's officers and men were stationed in New Orleans or in Washington, Mississippi Territory.[5]: 1 Battle at TippecanoeOn November 7, 1811, a detachment of riflemen attached to the 4th Infantry Regiment fought at Tippecanoe. Because rifles took longer to load than muskets, the riflemen were armed with muskets. During a night action, the riflemen inflicted heavy casualties of Native American forces.[2]: 24–27 [4]: 112 Service in the War of 1812Operations in FloridaA group of Georgians, calling themselves "Patriots", crossed into Spanish East Florida and, on March 17, 1812, captured Amelia Island from the Spanish garrison. The Patriots then "ceded" Amelia Island and the surrounding area to the United States. On April 12, 1812, two companies of the regiment under the command of then Lieutenant Colonel Thomas A. Smith occupied Fort Mose, Spanish East Florida as part of the Patriot War.[2]: 24–27 [6] The riflemen received little support from the US Government or the Patriots. Smith attempted a siege of St. Augustine, Florida, but his supply lines were not secure and the Spanish garrison of Castillo de San Marcos threatened his command. The Spanish counterattacked Fort Mose and Smith retreated to an encampment further from St. Augustine, Florida. On May 16, 1812, the Spanish set fire to Fort Mose to prevent its reoccupation. Troops retreated to Point Petre, Georgia under the leadership of Captain Abraham A. Massias.[2]: 27–28 All US troops were withdrawn from East Florida by May 1813.[5]: 2 [6] Raid on GananoqueWhen war was declared on June 18, 1812, Captain Benjamin Forsyth's company of the regiment was stationed in New York City. In July 1812, Forsyth led his company to Sacketts Harbor, New York from which, on September 20–21, 1812, he, his company and supporting militia attacked British stores at Gananoque, Upper Canada. Forsyth surprised the Canadian militiamen and was able to capture muskets, ammunition and prisoners. Forsyth's party set fire to stores they could not carry and returned safely to Sackets Harbor from the raid. Forsyth's losses were one man killed and one wounded.[2]: 29 [7][8]: 50 Skirmish near the garrison of OgdensburgBenjamin Forsyth needed firewood for his barracks. Forsyth sent Bennet C. Riley with about a half dozen riflemen upriver to gather some wood in a boat. Riley and his men tried to stay by their side as close as possible and as stealthily as possible. But a group of British gunboats spotted Riley's boat crew and set upon them. Benjamin Forsyth and his riflemen rowed out on their boat providing sniper covering fire for Riley's crew. The British gunboats were held at bay as Riley and Forsyth both withdrew safely back to their fort in their boats.[9] Attempted Deployment to Queenston HeightsIn October 1812, two companies of riflemen were assigned to participate in the Battle of Queenston Heights; however disagreement between Major General Stephen Van Rensselaer and Brigadier General Alexander Smyth resulted in those companies being withdrawn because Smyth thought it more important that they clean their camp following a storm. Ultimately, the U.S. attempt to take Queenston failed.[8]: 42 Orchestrating a Raid into French CreekAlexander Smyth who was a commander of the Regiment of Riflemen orchestrated and ordered a raid on the British that would take place on November 28, 1812. Although Smyth and none of his riflemen took part in the raid. Smyth did do the planning and setting the objectives for the raid. The American raiding force consisted of 770 Regulars and sailors. Smyth instructed the regulars and sailors to spike the British artillery guns and destroy a bridge in preparation for an invasion of Canada. The American raiding force set fire to a post, spiked all the cannons, and captured 34 enemy combatants. The raiders were not able to destroy the bridge but only damage it by removing a third of the plank. The British lost 13 killed and 44 wounded. The American raiders withdrew safely back to American lines with their prisoners while the Americans lost 25 killed, 55 wounded, and 39 captured.[10] Raid at ElizabethtownForsyth was promoted to major during the winter and on February 6–7, 1813, led a multi-company force of the regiment in a raid on Elizabethtown, Upper Canada, from Ogdensburg, New York, which resulted in the freeing of American prisoners, the capture of Canadian prisoners and the re-capture of arms that had been taken by the British at the Battle of Detroit. Forsyth was brevetted to lieutenant colonel for distinguished service with a date of rank of February 6, 1813.[3]: 430 [7]: 92 [8]: 52 Raid on SeminolesIn December 1812, Tennessean volunteer leader John Williams led 240 Tennessee mounted volunteers with 220 Georgia troops led by Rifleman Colonel Thomas Adams Smith conducted a raid. Thomas Adams Smith was the only Rifleman who took part in this raid. The combined American militia force marched on Payne's Town on February 8, 1813. The Americans engaged the Seminole warriors for several hours before driving them off. The Americans set their base of operations. The Americans conducted raids on nearby villages destroying homes and crops. The Americans killed 20 Seminole warriors, burned 386 houses, destroyed 2,000 bushels of corn, and destroyed 2,000 deerskins. The Americans took 300 horses, 400 head of cattle, and 9 Seminoles/Africans as prisoners. The Americans then withdrew back to friendly lines on February 24, 1813.[11] Raid across the Canadian borderA week later after the raid on Elizabethtown, a few number of Forsyth's riflemen including Lieutenant William C. Baird raided across the River of the border between America and Canada. The American riflemen captured 3 farmers and a team of horses.[12] Battle of OgensburgForsyth proved to be an aggravation to the British commanders in Upper Canada and on February 22, 1813, he and his troops were driven out of Ogdensburg by a superior force of British soldiers led by Lieutenant Colonel George MacDonnell. The Americans were used to seeing British troops drilling on the frozen Saint Lawrence and were taken by surprise when they suddenly charged. The riflemen in the fort held out against the frontal attack, mainly because the British guns became stuck in snow drifts, and American artillery, under Adjutant Daniel W. Church of Colonel Benedict's regiment and Lieutenant Baird of Forsyth's company, fired on the British with mixed results. At the outskirts of the town, American militia bombarded the British force with their artillery. A British flank party maneuvered to the least guarded part of the ground and broke through the weak part of the defense. American militia who had been dislodged from their position fell back while conducting a harassing fire by shooting at the British from behind houses and trees. More British flankers maneuvered through the gap to strike the American militia's main defense from behind. Soon, the British attacking from the front and rear overran the position. The remaining American militia ran farther into the village where some of the American militiamen took cover in or behind houses provided harassing fire against the British. But the British overran the position with Forsyth's position as the remaining obstacle.[13] Benjamin Forsyth had placed his riflemen behind stone buildings as shelter. When the British came closer, Forsyth's riflemen and his artillery opened heavy fire causing a number of casualties on the British raiders. But the British soon overran the position and the Americans retreated. Benjamin Forsyth and his surviving riflemen all withdrew. The American militia either surrendered, got captured, fled to other towns, or hid amongst the civilian population. The British burned the boats and schooners frozen into the ice, and they carried off artillery and military stores.[14] Forsyth requested re-enforcements from Colonel Alexander Macomb at Sacketts Harbor to retake Ogdensburg, but Macomb provided no troops and Forsyth led his riflemen back to Sacketts Harbor.[2]: 31–33 [8]: 53 Spearheading and raiding YorkForsyth's company was ordered to join the main American force at Sackett's Harbor rather than reoccupy Ogdensburg. They led the American assault at the Battle of York. Benjamin Forsyth and Bennet C. Riley spearheaded the raid in York. It would be a massive large force of 1,700 regulars including riflemen in 14 armed vessels. Forsyth and Riley led the way with their riflemen at the front to make a beachhead. Forsyth, Riley, and the riflemen landed at the beach. The Americans engaged the British regulars, Indians, and Canadians who were trying to set up a defense. Forsyth, Riley, and their riflemen hid behind trees and logs and never exposed themselves except when they fired, squatting down to load their pieces, and their clothes being green they were well camouflaged with the bushes and trees. The place chosen by the Americans for landing was very advantageous for their troops, being full of shrubs and bushes. The Americans immediately covered and cut off the British-allied forces, with little or no danger to the Americans. The British and their allies, suffering many casualties, withdrew from the field. The Americans suffered moderate casualties from resistance from British-allied remnants, magazine explosion, or other circumstances. The American raid at York was successful, however it was not without some controversy. Even though the civilians were not harmed. Many of their belongings were looted by the Americans and many private property were burned to the ground. Despite that the American commander Pike who was killed in this raid explicitly instructed his soldiers not to conduct any looting or burning private property. The Americans, after conducting their raid, withdrew from York. Forsyth, Riley, and the rest of their riflemen also withdrew.[15][16][2]: 34–35 Spearheading an assault at Fort GeorgeOn May 27, 1813, a battalion of the regiment commanded by Forsyth executed another amphibious assault and participated in the capture of Fort George, Upper Canada. After taking the fort, US troops attempted to pursue the retreating British forces but Major General Morgan Lewis recalled the battalion when he feared an ambush.[17]: 25 Ambush at Black Swamp RoadIn July 1813, Benjamin Forsyth and his riflemen with the aid of Seneca Warriors and American militia under the command of militia commander Cyrenius Chapin conducted a successful ambush against the British allied Mohawks near Newark, Ontario. The American riflemen and Seneca warriors would hide on both sides of the road. While a group of Seneca and American militiamen on horses led by Cyrenius Chapin would lure the Mohawks to the ambush site by conducting a feigned retreat. Cyrenius Chapin and his combined group of mounted militia and Seneca riders rode near the Mohawks, taunted them, and rode back down the road. The Mohawks pursued. When the enemy entered the kill zone, Benjamin blew his bugle as a signal to initiate the ambush. The hidden American riflemen and Seneca gunners rose out of their concealment and opened a heavy fire on the Mohawks. The Mohawks lost 15 killed and 13 captured including a British interpreter. A few of the Mohawks escaped. The American riflemen, militia, and Seneca allies withdrew back to friendly lines with their prisoners.[18] Raid near LacolleAmerican General Wade Hampton I led a raid in September 1813 into Champlain. After the raid, General Wade Hampton withdrew back to American lines. Major Benjamin Forsyth was stationed in Chazy. He raided into Canada capturing some British goods and several horses near Lacolle.[19] Raid at OdelltownForsyth went on another raid at Odelltown capturing a lot of goods. Many of the goods were distributed among the American soldiers as recompense for their baggage lost at Ogdensburg.[19] Diplomacy MissionAn American rifleman who was an officer of Forsyth's command came under a flag of truce to British lines to conduct diplomacy. The British commander J. Ritter of the British sixth light infantry presented a roll of carpet to the American officer as a gift to an American official whose carpeting was destroyed in his home by a previous British raid. The American officer of Forsyth's command returned to American lines presenting the carpet gift to the American high command.[19] Capturing and interrogating prisonersBennet C. Riley was out patrolling with his other riflemen who were acting as sentries. Riley, Forsyth, and their riflemen were performing paramilitary operations in British Canada in support of America's invasion. Riley's fellow sentries captured 2 Canadian teenage boys who were acting as spies. Riley brought them before Forsyth. Forsythe and Riley did not wish to kill these teenage spies as they were just young boys. They had no intention of killing young teenage boys. So Forsyth and Riley bluffed the teenage spies into talking by pretending to threaten them with death. The ruse seemed so convincing that the teenage boys told Forsyth all valuable intelligence about a blockhouse that was being built to contest the American advance. Then Forsyth and Riley released both teenage spies. Forsyth sent Riley to inform the American generals of the blockhouse. After Riley informed the American generals of the blockhouse, the American army easily overtook the blockhouse and routed the British-Canadian defenders.[20] Raid on Missisquoi BayAfter American Major General Wade Hampton encamped his division at Four Corners, New York, in September 1813. Wade Hampton ordered American colonel Isaac Clarke to undertake a “petty war” at the border between Vermont and Lower Canada to stifle smuggling and to divert British attention from his force.On October 12, 1813. Issac Clarke with about 102 riflemen crossed in boats from Chazy, New York, to a point near Philipsburg, Lower Canada, on Missisquoi Bay (the eastern basin in the northern reach of Lake Champlain) and seized the village, which was guarded by a detachment of the 4th battalion of Select Embodied militia of Lower Canada militia. A brief skirmish erupted in which the Canadian militia were defeated. Clarke took at least 100 prisoners, confiscated livestock and stores, and returned to Chazy. Isaac Clarke claimed in his account that he had taken 101 prisoners, killed 9 enemies, and wounded 14.[21][22] Spearheading in the Battle of Chrysler's FarmForsyth's riflemen where then employed as an advance force and on November 7–9, 1813 they engaged a large Canadian force at Hoople's Creek near Cornwall, Upper Canada, concurrent with the Battle of Crysler's Farm. Although the riflemen performed well and the Americans persevered at Hoople's Creek, the Canadians drove the Americans from the farm and Major General James Wilkinson withdrew to winter quarters.[2]: 39–40 Spearheading and besieging the British blockhouse Lacolle MillsOn March 30, 1814, Benjamin Forsyth, Bennet C. Riley, and their riflemen spearheaded an attack on British-allied forces who were retreating back to a blockhouse. The main American army followed behind. The British and their allies fell back into their blockhouse. The British and their allies were deeply entrenched and fortified in their blockhouse. Riley, Forsyth, their riflemen, and the American army besieged the blockhouse with rifle/musket fire and artillery. But the British held them off to great effect. After a long siege, the American force withdrew.[23][24] British casualties were 11 killed, 44 wounded, and 4 missing.[25] American casualties were 13 killed, 128 wounded, and 13 missing.[25] Ambush at Big Sandy CreekRiflemen under the command of Major Daniel Appling participated in the Battle of Big Sandy Creek on May 30, 1814, during which they ambushed and captured a large detachment of British sailors, including two Royal Navy captains, and Royal Marines, sparing a shipment of large cannon from capture.[2]: 50–51 Appling was brevetted to lieutenant colonel on May 30, 1814, for gallantry and to colonel on September 11, 1814, for distinguished service.[3]: 168 Long-Range PatrolLater in the year on June 24, 1814, Major Forsyth was promoted to brevet Lieutenant Colonel the following winter. He was active in skirmishing and patrolling north of Lake Champlain in the late spring and summer. On one such patrol, Benjamin Forsyth, Bennet C. Riley, and 70 of their riflemen went out from their base from Chamberlain to patrol near the Canadian border. While the Americans were patrolling in a loose skirmishing V formation. Forsyth stopped his men and had a secret conversation with Riley. Forsyth whispered to Riley that he sensed that there were Indians and Canadians hiding in ambush. Forsyth commanded Riley to tell the rest of the riflemen to casually withdraw so as not to cause the Indians and Canadians to be eager to launch their ambush. Riley suggested to Forsyth that they should withdraw to a tavern on the outskirts of this town and take shelter in it. Riley explained that they could conduct sniper fire from within the cover of the tavern. While Riley and Forsyth were marching their column casually for ten minutes. The Canadian-Indian force caught up and opened fire. All 70 American riflemen opened a simultaneous volley fire killing or wounding a number of Canadians and Indians. The Americans retreated by leapfrogging. One group of riflemen would provide covering fire while one group of riflemen retreated. The American repeated this process until they reached the tavern. Riley, Forsyth, and all their riflemen went inside the tavern. The Americans sniped at the enemy from behind covered and concealed positions within the tavern. The Americans killed or wounded more Canadians and Indians. After this intense engagement, the enemy fully retreated. The Americans were victorious. 1 American rifleman was killed and 5 wounded. The Canadian-Indian force are reported to have lost 3 killed and 5 wounded. The Americans later withdrew back to American lines in Chamberlain.[26][27][28] Raid to capture a spyBenjamin Forsyth and his riflemen conducted a raid into Canadian territory and captured a British spy. Forsyth and his riflemen withdrew back to American lines with their captured British spy.[29] Ambush at OdelltownBenjamin Forsyth was killed in June 1814 in a clash at Odelltown, Lower Canada.[3]: 430 On 28 June 1814, Benjamin Forsyth, commander of the American Regiment of Riflemen, advanced from Chazy, New York to Odelltown, Lower Canada intending to draw a British force of Canadians and American Indian allies into an ambush.[30][28] Upon arriving at the British positions, Forsyth sent a few men forward as decoys to make contact.[30][28] When the British responded, the American decoys conducted a feigned retreat, which successfully lured 150 Canadians and American Indian allies into the ambush site.[30][28] During the ensuing fight, Forsyth needlessly exposed himself by stepping on a log to watch the attack and was shot and killed.[30][28] Forsyth's riflemen, still hidden and now enraged over the death of their commander, rose from their covered positions and fired a devastating volley.[30][28] The British were surprised by the ambush and retreated in confusion, leaving seventeen dead on the field.[30][28] Forsyth was the only American casualty.[30][28] Even though Forsyth was killed, his feigned retreat and ambush succeeded at inflicting heavy casualties on the British force.[30][28] Ambush at Conjocta CreekOn August 3, 1814, another detachment of riflemen under the command of Major Lodowick Morgan ambushed and repelled a British raid at Conjocta Creek near Buffalo, New York, prior to the Siege of Fort Erie. Morgan and his troops, along with elements of the 4th Regiment of Riflemen, helped relieve the siege.[2]: 56–60 Lodowick Morgan's hit-and-run attack on British forcesAfter repelling the British at Conjocta Creek, Morgan was ordered by American high command to perform a reconnaissance with his riflemen on the British. Morgan was also given orders to attack the British and draw them out of their entrenched positions if possible.On August 5, 1814, Morgan attacked the British and drove them back to their lines; and for two hours he maneuvered in a way calculated to draw the main body out, but without success. Morgan withdrew back to the American camp with a loss of five men killed and four wounded. British casualties were ten British soldiers and five British-allied Native Americans killed.[31][32] Skirmish near Fort ErieOn August 11, 1814. There were British forces with artillery sheltered by breastworks near Fort Erie. American Captain Benjamin Birdsall with 160 American riflemen of the 4th regiment of riflemen attacked two British pickets driving them back. British casualties were 10 killed while the Americans suffered 1 killed and 3 wounded.[32] Lodowick Morgan's final hit-and-run attack on British forcesOn August 12, 1814. Major Morgan launched another hit-and-run attack on the British to support a detachment of 80 riflemen under American Captain Birdsall who had been sent to cut off a working party of the enemy, engaged in opening an avenue for a battery through the woods. The enemy were driven off. Though the British enemy were driven off, they were soon reinforced by more reinforcements. The firing lasted more than Major Morgan expected. The reinforced British soon proved too overwhelming. So Major Morgan gave the signal to withdraw by blowing his bugle. But at the same time a musket ball hit Major Morgan in the head killing him. Morgan's men carried his deceased body and successfully withdrew from the field.[33][3]: 726 Ambushing and killing an enemy leaderOn August 10, 1814, Bennet C. Riley and a dozen American riflemen would conduct a mission behind enemy lines to kill or capture an enemy Canadian Indian tribal partisan leader named Captain Joseph St Valier Mailloux. Riley and his dozen riflemen infiltrated Odeltown in Canada silently. There was an enemy sentry. One of the American riflemen crept on the sentry and silently killed him with his tomahawk. Riley and his men hid the dead sentry's body. One of the American riflemen put on the dead sentry's uniform to trick captain Mailloux into a false sense of security when he came in to check on the sentry. The American rifleman disguised as the sentry stood guard while Riley and his other riflemen concealed themselves behind the bushes. Captain Mailloux came by and came closer to the sentry imposter to check up on him. Then Riley and his riflemen rose out of their concealment and demanded captain Mailloux to surrender. Captain Mailloux ran away. Riley's riflemen fired eleven shots hitting Mailloux eleven times. Mailloux was badly wounded. Riley and his riflemen carried Mailloux back to American lines in Chamberlain. The Americans tried to nurse Mailloux back to health, but Mailloux succumbed to his wounds and passed away.[34][35] Repelling the British assault at Fort ErieOn August 15, 1814, the British launched an all out attack on the American held Fort Erie. The Americans were heavily entrenched and fortified. The British breached the fort after suffering heavy casualties. The American riflemen under Captain Benjamin Birdsall charged against the British in the fort with some American regulars. But the American regulars were driven back with Captain Benjamin Birdsall wounded. But the other American forces drove the British out of the fort thus ending in an American victory.[36] Sortie at Fort ErieDuring the siege of Fort Erie, the British suffered heavy casualties after making costly infantry assaults on the American entrenched fort. The Americans who were deeply entrenched in their fort's defenses suffered minor casualties. The American commander Jacob Brown then wanted to a sortie on the British to cause heavier casualties on the British, disable their artillery, and destroy the magazine supplies. Peter B. Porter was to conduct one sortie while James Miller was to lead the other. Peter B. Porter would lead a raiding sortie of militia and regulars while Miller would lead a raiding party of regulars. The American riflemen would take part in this sortie. The American raiders would infiltrate British lines to conduct their mission. Porter secretly led his force traveling along a hidden road using the cover of the woods while Miller led his force secretly in a ravine. The American raiders struck by surprise and full ferocity. In the chaotic attack, the Americans destroyed 3 batteries of cannons, blew up the magazine, and inflicted heavy casualties on the British. Afterwards, all the American raiders withdrew back into the fort. The British suffered 115 killed, 178 wounded, and 316 missing. The American raiders led by Porter and Miller suffered 79 killed, 216 wounded, and 216 missing. Even though the American sortie completed their objectives, it was still costly in terms of casualties for the Americans. Some time later, the entire American force at fort erie would evacuate to Sackets Harbor. The American riflemen who took part in this sortie suffered 11 dead and 19 wounded.[37][38][39] Battle of PlattsburghDaniel Appling and 110 of his riflemen were deployed to Plattsburgh to prepare for a British invasion. The British invasion numbered at least 11,000 regulars against an American force of at least 6,354 troops. Appling and his riflemen were stationed in Chazy. While the larger numerically superior British army was marching, Appling and his riflemen fell back conducting delaying actions. The riflemen harassed the British, destroyed bridges, and felled trees to place abatis on the road. The American riflemen, regulars, and militia regrouped after crossing the bridge at Saranac river and destroying the bridge. The riflemen, militia, and regulars held out until the British lost the will to fight any longer and withdrew in defeat.[40][3][41] Final Engagement at Fort PeterThe regiment's last wartime action occurred after Britain and the United States agreed to end the war in the Treaty of Ghent. On January 13, 1815, Royal Marines and troops of the 2nd West India Regiment landed near Fort Peter, Saint Marys, Georgia. Captain Abraham A. Massais, who was commanding a force consisting of a company of the Regiment of Riflemen and a company of the 42nd Infantry Regiment, decided his command was outnumbered and executed a fighting retreat. The British demolished Fort Peter and re-embarked.[2]: 66–67 Post-war Following resumption of peace with Great Britain, the consolidated regiment was assigned to St. Louis, Missouri Territory. By 1817 the riflemen had contributed to the construction of Fort Armstrong, Rock Island, Illinois; Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; Fort Howard, Green Bay, Wisconsin and Fort Smith, Arkansas. The last was named after Thomas Adams Smith.[2]: 69 In 1819, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun ordered the Yellowstone Expedition, commanded by Colonel Henry Atkinson, to act as a warning against British incursions. Companies of the Regiment of Riflemen and elements of the 6th Infantry Regiment worked together to build Fort Atkinson, Nebraska (then an unorganized area of the Louisiana Purchase). In 1820, Congress later declined to fund further advances.[42][43] InactivationOn March 2, 1821, Congress passed an act establishing an Army with no provision for a rifle regiment. The regiment was inactivated on June 1, 1821.[3]: 141 Under an act of Congress dated August 23, 1842 the 2nd Cavalry Regiment was re-designated as the Regiment of Riflemen effective March 4, 1843. This act was repealed on April 4, 1844, and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment reverted to its previous designation. There is no clear connection between the earlier and later regiments.[3]: 143 References

External |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||