|

Reggio, Louisiana

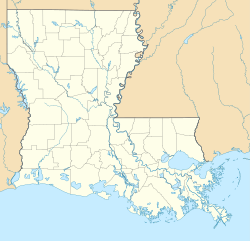

Reggio (/ˈrɛdʒioʊ/ REJ-ee-oh, French: [ʁɛdʒjo]), also known as Bencheque (/bɛnˈtʃɛkeɪ/ ben-CHEK-ay, Spanish: [benˈtʃeke]), is an Isleño fishing community located in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana.[1] The community was established in 1783 with the settlement of Canary Islanders along Bayou Terre-aux-Boeufs.[2][3] During the last decade of the eighteenth century, Louis de Reggio purchased land from the Isleños to establish a sugarcane plantation.[4] It is perhaps the only community in the United States that bears a Guanche-language name.[3] After the American Civil War, the community greatly expanded as Isleños moved deeper into the eastern portion of the Parish to engage in fishing, trapping, hunting, and Spanish moss gathering.[2][3] During the twentieth century, forces including urbanization, modernization, improved transportation, and natural disasters among others led to the migration of Isleños away from their traditional communities.[2][3][5][6] Following the complete destruction of Hurricane Katrina, only a handful of the original families returned to rebuild.[7][8] Etymology and usageThe community was originally named for the Montaña y Barranco de Bencheque, a mountain and ravine on the island of Tenerife near Icod de los Vinos where many of the Canary Islander colonists originated.[3][9][10] The name comes from the Guanche language and is believed to mean "el lugar de los árboles" ("the place of the trees") or "el lugar de la planta" ("the plant place").[10][11] An individual from the community is known as a Benchecano.[12] The latter name for the community, Reggio, originates from Louis de Reggio, the owner of the sugarcane plantation that was located in the same area.[4] The distinction between the Reggio plantation and the community of Bencheque had been maintained into the 20th century.[13] Towards the second half of the century, Reggio came to refer to the former area of the plantation and Bencheque. Isleños, particularly those who know Spanish, maintain this distinction and their descendants continue to do so today.[3][5][10][11][12] Legal descriptions of land tracts in the settlement use Bencheque while Reggio has been used by St. Bernard Parish Government, the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and other organizations.[14][15][16] HistoryBeginning in 1779, Canary Islanders came to be settled by the Spanish government along Bayou Terre-aux-Beoufs in what would become St. Bernard Parish.[2] The entire settlement was referred to as the Población de San Bernardo (St. Bernard Population) and was composed of various establecimientos (establishments) or puestos (posts), which were smaller communities.[3] These establecimientos ran along Bayou Terre-aux-Boeufs starting just past the western limit of Saint Bernard and extending to Delacroix Island. One of the larger communities, established in 1783, was the quinto establecimiento (fifth establishment) which would come to be known as "Bencheque."[3] In the 1790s, the New Orleanian Louis de Reggio purchased land from the Isleños to establish a sugar plantation.[4][17] The plantation eventually extended from the Olivier plantation all the way to Wood Lake.[3][18] In 1836, the Mexican Gulf Railroad was established and linked the Reggio plantation, along with other plantations of St. Bernard Parish, to the city of New Orleans.[3][4][17] Following the American Civil War, Isleños began to relocate to Bencheque to fish, trap, hunt, and gather Spanish moss.[2][3] While changes came to the rest of Louisiana following the Reconstruction era, the Isleños remained largely rural and unchanged.[2] With the turn of the twentieth century, the benchecanos suffered various hardships. The 1915 New Orleans hurricane left many Isleños dead and every house at Bencheque was either badly damaged or completely destroyed.[19] Two years later, the Spanish flu swept through St. Bernard Parish and required the mass burial of over one thousand people, mostly Isleños, at St. Bernard Catholic Cemetery.[20] The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and subsequent dynamiting of a levee at Caernarvon left the community completely inundated.[21] Increased urbanization, greater access to education, and improved roads led to residents leaving in search of security and job opportunities.[2][3][5][6] In 1965, Hurricane Betsy made landfall with Louisiana and once again leveled the homes of the community.[22] This event dealt a serious blow to the prevalence of Isleño culture in the traditional Isleño communities of the St. Bernard Parish.[6] In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated the region. Very few of the original families returned to the community to rebuild and new ones moved into available property.[7][8] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||