|

Purog Kangri

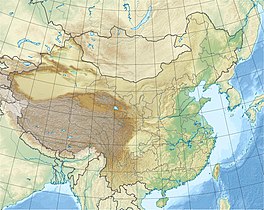

Purog Kangri (Tibetan: བུ་རོགས་གངས་རི, Wylie: bu rogs gangs ri) is an ice field in the Tibetan Plateau, in Nagqu, China. It is shrinking rapidly. LocationPurog Kangri was discovered by Chinese and American scientists around 1999. The other two are in the Arctic and the Antarctic.[1] Purog Kangri is in the Nagqu prefecture-level city of Tibet, China. It is in a harsh mountain environment that is not accessible to tourists.[2] It is about 150 kilometres (93 mi) from the double lake.[3] The Purog Kangri ice field is at 33°51′18″N 89°48′18″E / 33.8550°N 89.8050°E at an elevation of 6,072 metres (19,921 ft) above sea level.[4] The ice field is the largest in the North of the Tibetan Plateau. It is made up of several ice caps with a total area of 422.58 square kilometres (163.16 sq mi) as of 2002, and a volume of about 52 cubic kilometres (12 cu mi). The glacier snow line is 5,620 to 6,860 metres (18,440 to 22,510 ft) above sea level.[5] The ice field is radial, with over 50 tongues of ice of different lengths that extend from the ice field through wide and shallow valleys. In the areas with lower tongues there are many ice pyramids.[5] ClimatePurog Kangri is near the boundary between the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, where the weather is driven by the monsoon cycle, and the northern part where it is driven by continental westerly storms coming from the Arctic and the North Atlantic. The latter process has the greatest effect on the ice field.[6] The Tibetan Plateau and Himalaya hold the largest amount of ice outside the Arctic and Antarctic. Meltwater from the glaciers feeds the Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, Brahmaputra and Ganges rivers.[4] The glaciers have been shrinking since the Little Ice Age.[5] ShrinkageIce cores were recovered from the Purog Kangri ice field in 2000, filling a gap in knowledge of climate change in the Central Tibetan Plateau.[7] The longest core was 213 metres (699 ft). The upper 102 metres (335 ft) covered the last 1,000 years, and was analyzed along its length for the δ18O oxygen isotope ratio.[8] The results, correlated and checked against ice cores from other locations, showed a sharp increase in temperature starting in the late 19th century.[9] Between 1960 and 2004 the glaciers in the region have shrunk in volume by 389 cubic kilometres (93 cu mi), or 7%, and in area by 3,248 square kilometres (1,254 sq mi), or 5.5%. The rate of shrinkage is expected to accelerate, with 2/3 of China's glaciers gone by 2060.[1] Measurements using interferometric synthetic-aperture radar showed that the ice field became slightly thicker in 2011–2012, by about 0.44 metres (1 ft 5 in), then in 2012–2016 thinned each year by 0.13 to 0.52 metres (5.1 in to 1 ft 8.5 in). This was mainly due to a steep drop in annual precipitation, from 405.13 to 207.19 millimetres (15.950 to 8.157 in).[10] Another study using TanDEM-X SAR data sets from 2012 and 2016 indicated annual surface thinning of 0.317 metres (1 ft 0.5 in) with a 0.027 metres (1.1 in) margin of error.[11] Notes

Sources

|

||||||||||||||||