|

Pure autonomic failure

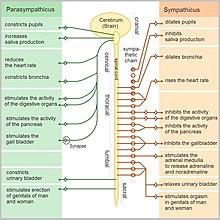

Pure autonomic failure (PAF) is an uncommon, sporadic neurodegenerative condition marked by a steadily declining autonomic regulation.[3] Bradbury and Eggleston originally described pure autonomic failure in 1925.[4] Patients usually present with orthostatic hypotension or syncope in midlife or later. In addition, genitourinary, thermoregulatory, and bowel dysfunction can be signs of autonomic failure.[5] Pure autonomic failure originates from peripheral autonomic nervous system lesions.[6] The diagnosis of pure autonomic failure relies on the absence of other neurologic abnormalities, specifically Parkinsonism, cognitive impairment, cerebellar ataxia, or tremors, and on compatible clinical features of subtle, progressive pan autonomic failure, most notably orthostatic hypotension.[7] Signs and symptomsThe majority of symptoms that patients with PAF exhibit are associated with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension, or orthostatic hypotension brought on by severe sympathetic failure. Within three minutes of standing up straight, orthostatic hypotension is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg or a drop in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg.[7] About half of PAF patients also have concurrent supine hypertension, even though all PAF patients by definition have orthostatic hypotension.[8] For some PAF patients, genitourinary dysfunction may be the first or presenting symptom. Urgency and frequency are the most common bladder symptoms in PAF, but more severe dysfunction including urinary retention and incontinence can also occur.[5] Over half of PAF patients report having constipation,[9] which is frequently an early sign of the illness.[10] About half of all PAF patients report abnormal sweating, which can manifest as either excessive or decreased sweating, with the latter being the result of compensatory hyperhidrosis.[11] PathologyThe pathology of pure autonomic failure is not yet completely understood. However, a loss of cells in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord has been documented, as has a loss of catecholamine uptake and catecholamine fluorescence in sympathetic postganglionic neurons. In general, levels of catecholamines in these patients are very low while lying down, and do not increase much upon standing. TreatmentPharmacological methods of treatment include fludrocortisone, midodrine, somatostatin, erythropoietin, and other vasopressor agents. However, often a patient with pure autonomic failure can mitigate his or her symptoms with far less costly means. Compressing the legs and lower body, through crossing the legs, squatting, or the use of compression stockings can help. Use of an abdominal binder is even more effective. Also, ingesting more water than usual can increase blood pressure and relieve some symptoms.[citation needed] HistoryIn 1925, Bradbury and Eggleston first characterized three patients seemingly with a common syndrome, with what they described as "the occurrence of syncopal attacks after or during exertion or even after standing erect for some minutes. Other features in the three patients are a slow, unchanging pulse rate, incapacity to perspire, a lowered basal metabolism and signs of slight and indefinite changes in the nervous system. Each of these patients felt much worse during the heat of summer."[12][13] Further research identified multiple causes for these syndromic findings, now grouped as primary autonomic disorders (also called primary dysautonomia), including Pure Autonomic Failure, Multiple System Atrophy, and Parkinson's. The primary differentiating characteristic of Pure autonomic failure is decreased circulation and synthesis of norepinephrine, and dysfunction localized peripherally. It is relevant to note that progression to central nervous system neurodegeneration can also occur.[13] EponymIt is also known as Bradbury-Eggleston syndrome, named after Samuel Bradbury and Cary Eggleston who first described it in 1925.[14][12][15] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||