|

Protectorate of Wallis and Futuna

The Protectorate of Wallis and Futuna was a French protectorate from March 5, 1888, to July 29, 1961, over the islands of Wallis, Futuna, and Alofi, in the Pacific Ocean. It was established at the request of the customary kings, under the influence of Catholic Marist missionaries who had converted the population in 1840-42 and sought French protection against the advance of Protestants in the region. In April 1887, the protectorate over Wallis was signed. It was extended to Futuna the following year, although these islands were administratively attached to New Caledonia until 1909. Given the islands' low strategic interest and remoteness, there was no real colonization. The protectorate is headed by a resident sent by France. Residing in Wallis, he is responsible for maintaining law and order, managing the budget and collecting taxes, building infrastructure, and also has the power to validate the appointment of customary kings. Nevertheless, the French administration has to contend with the customary powers (Lavelua in Wallis, kings in Futuna, and their chiefdoms), which have authority over the Wallisians and Futunians, with the powerful Catholic Church, which oversees the population and manages education as well as morality control, and with the merchants, some of whom get involved in politics. Nevertheless, some residents tried to increase their power, such as Jean-Joseph David, who sought to develop Wallisian infrastructure and exports at breakneck speed in the 1930s. Futuna, on the other hand, is difficult to reach, and the French administration is represented by a missionary. Futuna's trajectory therefore differs markedly from that of Wallis. Inhabitants relied on subsistence farming and fishing to meet their needs, and these Polynesian societies, organized around give-and-take, were unaware of the market economy. The only commercial activity, encouraged by France, was the export of copra, but this collapsed in the 1930s.[1]  The Second World War represented a major turning point: by remaining loyal to the Vichy regime, the islands were cut off from the world for 17 months, before being recaptured by the Free French and Wallis taken over by the American army. The construction of infrastructures, the arrival of strong purchasing power, and the discovery of the Western model of society upset the socio-economic and political balance. A large-scale emigration to New Caledonia and the New Hebrides began, reinforced by the dilapidated economic situation following the departure of the Americans in 1944. The protectorate became “archaic”. The population voted overwhelmingly in favor of a change of status in the 1959 referendum, and on July 26, 1961, the protectorate came to an end: Wallis and Futuna became an overseas territory.[2] Context Geographical location The protectorate covers the Wallis Islands (a central island surrounded by a lagoon with several islets) and the Horn Islands (Futuna and Alofi). Located in the Pacific Ocean, they belong to the cultural and historical area of Polynesia.[2] The nearest islands are Tonga to the south (British protectorate from 1900 to 1970), Fiji (British colony from 1874 to 1970) to the south-west, and the Ellice Islands and Gilbert Islands (British protectorates from 1892 to the 1970s, now Tuvalu and Kiribati) to the north, Tokelau (British protectorate, included in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in 1916) to the northeast, and Samoa to the east, divided between German Samoa (1900-1914), which came under New Zealand sovereignty in 1920, and American Samoa (1899-present). The French protectorate was thus surrounded by British and American possessions. The closest French possessions are the New Hebrides (a Franco-British condominium from 1907 to 1980) and New Caledonia, a colony conquered in 1853 and made an overseas territory in 1944. The French establishments in Oceania (now French Polynesia), a colony from 1880 to 1946, are even further away. DemographicsIn 1842, the population of Wallis was estimated at 2,500, and that of Futuna at 900.[3] In the 20th century, the population of Wallis and Futuna grew steadily. From 1942 onwards, installing an American base in Wallis brought great prosperity, which encouraged the birth rate. This “golden age” ended in 1946, but led to a sharp drop in mortality.[4] As a result, Wallis experienced “demographic exuberance:”[4] between 1935 and 1953, the population grew by 45%. The vast majority of the inhabitants were Polynesians; the Western presence was minimal, limited to a dozen missionaries, a dozen merchants, and a resident of France.[5] There were also several hundred Polynesians from the surrounding islands, who in 1900 accounted for 10% of Uvea's population and were well integrated into Wallisian society.[6]

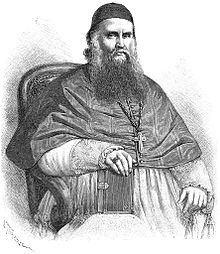

Social and political organization The Wallis and Futuna islands are structured around village chiefdoms headed by a customary “king” (hau in Wallisian, sau in Futunian), chosen from among the noble families ('aliki). Custom plays a very important role in the life of the islanders.[8] When Westerners arrived in the 19th century, Futuna was divided into two kingdoms: Alo and Sigave, while the kingdom of Uvea encompassed the whole island of Wallis.[9] The customary kings had authority over land ownership: no foreigner could buy land, and only a right of use could be granted.[10] In 1837, French Marist missionaries arrived on both islands and, within a few years, converted the population to Catholicism. They grouped the settlements on the coast and provided a framework for the royal power.[11] In Wallis, the rules established by the missionaries changed the social order by freezing customary organization, weakening the aristocracy through mixed marriages,[note 1] and creating a local clergy to establish their spiritual and temporal authority. The mission thus succeeded in taking a place in the traditional customary organization, preserving or adapting Wallisian customs.[10] As historian Frédéric Angleviel notes, “at the time of the arrival of the Westerners, the Wallis and Futuna entity could be considered non-existent, the two archipelagos being entirely independent of each other.”[5] Traditional links existed between these islands and the other Polynesian archipelagos, but travel (tāvaka) was forbidden by missionaries to protect Wallis and Futuna from outside influences.[12] TimelineOrigins As soon as the Marist Fathers arrived in Wallis and Futuna in 1837, the missionaries understood the importance of official French protection for the islands, which they had converted to Catholicism. Indeed, at the end of the 19th century, rivalries between Catholics and Protestants were strong. As Jean-Claude Roux sums up, “behind the missionary screen, a delicate game between sailors, consuls, colonists, and merchants was going to be played for a long time, for the control of the South Pacific archipelagos.”[13] The aim was to counter the influence of the Tongans, who had recently converted to Methodism and were making several attempts to extend their religion to Wallis. Under the influence of the Marist Fathers, the Wallisian sovereign (Lavelua) made an initial request to France for a protectorate in February 1842, then again in October of the same year, by addressing the various ship captains who docked at Wallis. According to Jean-Claude Roux, “the need to protect the Marist missionaries meant that the French Navy de facto took over Wallis and Futuna's affairs.”[14] At the time, the French Navy was seeking to increase the number of ports where its ships could call. However, France initially refused this request for a protectorate, as a diplomatic crisis had erupted with the United Kingdom, known as the “Pritchard Affair,” over the protectorate established in Tahiti: French annexations in the Pacific were then halted for a time to appease the British.[15] Beginnings of the protectorate (1887-1905) In the 1880s, the diplomatic and strategic situation changed. Following the British annexation of Fiji in 1874, which shattered the precarious balance between the two nations, the French also wanted to assert their position in distant Oceania.[16] Wallis and Futuna enjoyed renewed interest from the Ministry of the Colonies, and Tongan designs on 'Uvea increasingly worried the Wallisians. Missionaries also feared annexation by the British in Fiji.[5] In 1881 and 1884, the queen of Wallis, Amelia Tokagahahau (daughter of Lavelua Soane Patita Vaimu'a), repeated her request for a protectorate to French officers visiting Wallis. It wasn't until 1886 that the request for a protectorate from France was finally granted, fifty years after the installation of the Marist Fathers. Queen Amelia Tokagahau signed a protectorate treaty ratified by France on April 5, 1887, by decree. On November 29 of the same year, the kings Anise Tamole for Sigave and Malia Soane Musulamu for Alo also applied to join France. On March 5, 1888, a protectorate unifying Wallis and Futuna was signed.[17] The beginnings of the protectorate were imprecise: the decree of April 5, 1887, only concerned Wallis, and the island was attached administratively and financially to New Caledonia by a second decree on November 27, 1887 - although the precise terms were not specified. Futuna was finally included in the protectorate on February 16, 1888.[18] It was not until 1909 (decree of June 10, 1909) that Wallis and Futuna were officially detached from New Caledonia and brought together as a single separate entity.[18] The sovereigns of Futuna and Wallis retain full customary authority over their subjects,[16] so this is not strictly speaking a conquest or colonization. The first French resident arrived in Wallis in 1888.[19] However, for Jean-Claude Roux, by 1900 “Wallis and Futuna were no longer of any strategic value.”[20] It wasn't until the late 1890s that the two islands began to show some economic interest, in the production of copra.[21] For Filihau Asi Talatini, “without the Catholic mission, France would not be present in the archipelago.”[22] Frédéric Angleviel speaks of a “symbolic” protectorate: “These statutes preserve the interests of the mission and the great chieftaincy while avoiding disproportionate expenditure by the Ministry of the Colonies about the small size of these archipelagos at the end of the world.”[5] The medical residents (1906-1942)Pierre Élie Viala arrived in 1905, followed by Jean-Victor Brochard (son of Victor Brochard), who strongly opposed the Catholic mission. After arriving in August 1909, Brochard had to leave Wallis in April 1910, but thanks to support in Nouméa, he was able to return to the island in 1912.[23] Annexation plans (1913)  A new protectorate treaty was signed with France on May 19, 1910. The text, valid until 1961, limited the powers of the King of Wallis, who was placed under subjection to the resident, and those of the missionaries. This new 1910 treaty was supposed to pave the way for annexation, officially requested by the King in 1913, under the influence of Resident Brochard.[24] On June 22, 1913, the cruiser Kersaint docked at Wallis and organized a ceremony where the French flag was raised in front of the royal palace. This was a source of concern for neighboring English-speaking countries. In France, annexation became a bill in 1917, passed by the Chamber of Deputies in 1920, but finally rejected by the Senate in 1924.[25] After several “disastrous initiatives”,[23] Resident Brochard left Wallis and Futuna for good in 1914. Between 1914 and 1926, there was no resident physician.[23] Alain Gerbault on Wallis (1926)In 1926, navigator Alain Gerbault ran aground on the reef at Wallis. Staying on the island for several months to repair his ship, he took an interest in local politics and openly criticized the French mission and administration. This provoked unrest among the local population, who protested against King Tomasi Kulimoetoke I and the resident in December 1926. Following these events, five ringleaders were tried and exiled to Nouméa on March 11, 1927, at the request of resident Barbier. However, they were amnestied on August 31, 1927, and returned to Wallis in May 1929.[26] The copra crisisIn the early 1930s, Wallis and Futuna were hit by a parasite, oryctes rhinoceros, which contaminated coconut palms and led to a collapse in copra production, the territory's main export at the time.[23] King David (1933-1938)The protectorate of Wallis and Futuna was marked by the figure of Jean-Joseph David.[27][28] This military doctor arrived in Uvea in 1933 and took charge of the protectorate. He was the only settler on the island (apart from some fifteen missionaries and two traders).[29] “David was not only a doctor, but also a resident, chief of works, justice of the peace and “king;” he set up a new hospital and school, and developed sports in order to work towards the physical improvement of the Wallisians, whom he also sought to put to (forced) work to develop the island.[30] In 1934, he built the island's first public school, and in 1935 a hospital and maternity hospital.[23] He set up major works: road maintenance (in particular, he created the road from Mu'a to Hihifo), development of coconut plantations, and planting of new crops such as manioc. To achieve this, he hijacked the system of collective work, known as fatogia, found in Wallisian custom. “Through alliances with Wallisian nobles [...], he succeeded in setting in motion a system of customary drudgery, which he was to divert to the benefit [...] of developing the island's infrastructure, but pushing it to the limit.”[28] His authoritarianism earned him the nickname “Docteur Machette”[30] or lea tahi (Wallisian for “the one who gives orders only once,” who must be obeyed immediately).[31] He also had difficult relations with the Catholic mission. After the death of the previous king, Mikaele Tufele II, in 1933. He decided not to elect a new king and virtually obtained the customary status of Lavelua: he took the king's place in the kava ceremony, where the first cup was reserved for him.[28] His marriage to a Wallisian princess further established his status.[28] The population called him Te Hau Tavite, “King David.”[32] From 1933 to 1941, Uvea no longer had a king, and the customary prime minister, the kivalu, had the highest authority. Jean Joseph David also petitioned the population for the annexation of Wallis and Futuna by France, but the authorities in Paris and Nouméa refused, deeming the project too costly.[33] In 1939, he published L'œuvre française aux îles Wallis et Futuna, listing his actions and successes.[29] However, at the end of his stay, a typhoid epidemic affected the Wallisian population, due to the undernourishment caused by exertion.[28] For historian Claire Fredj, his experience was a failure.[30] After his Wallisian period, Jean Joseph David left for Haut-Nyong (Cameroon), where he implemented similar methods.[27] The Second World WarDuring the Second World War, while the other French territories in the Pacific rallied to Free France in 1940, the protectorate of Wallis and Futuna remained loyal to Vichy. This decision was mainly due to the attitude of Bishop Alexandre Poncet (1884-1973),[34] an anti-Republican and staunch Petainist.[35] Cut off from other French territories and surrounding islands (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) in the hands of the Allies, Wallis and Futuna suffered complete isolation for seventeen months.[35] Resident Vrignaud set up a police force to prevent a possible landing, although it was the Japanese who worried the population. On March 16, 1941, Vrignaud and the bishop supported the election of King Leone Matekitoga by the royal families, although the latter refused to pledge allegiance to Marshal Pétain.[35] An initial reconquest was envisaged by General de Gaulle in February 1941 but was canceled when it became public.[36] Faced with the Japanese advance in the Pacific, the Americans wanted to invest in the island to set up a military base. De Gaulle, anxious to preserve French sovereignty, negotiated for Free French troops to land first on Wallis. On May 27, 1942, a Free French expeditionary force seized Wallis, a day ahead of schedule, to assert French sovereignty over the island. Resident Léon Vrignaud was arrested without violence and replaced by a resident loyal to the Allies, Captain Mattéi.[35] The following day, the American army landed and set up a military base on the island. Futuna rallied to Free France two days later but was not taken over by the Allies.[35]  The American command landed 2,000 GIs on the island, and their numbers rose to 6,000 over the next two years.[16] In June 1942, the Seabees arrived on the island.[37] The Americans built numerous infrastructures: an air base at Hihifo for bombers (which became Hihifo airfield) and another at Lavegahau, a Seaplane base at Muʻa Point, a port at Gahi and a 70-bed hospital,[38] as well as roads.[39] They transported a large quantity of armaments, flak, aircraft, tanks, etc. This period had profound repercussions on Wallisian society: the American soldiers introduced numerous materials and built infrastructures that still bear their mark today. The GIs arrived with significant purchasing power, and Wallis became connected by plane and ship to the Samoan islands. As a result, writes Frédéric Angleviel, “this led to an extraordinary economic prosperity that was both unexpected, brief, and without lasting effects. A true consumer frenzy swept over the island despite regulatory efforts by the residency.”[40] The protectorate's tax revenues greatly increased due to customs duties on American products. The presence of the Americans disrupted the authority of the chiefs and missionaries. Indeed, commoners (tuʻa) quickly became wealthy by working for the American military. Consequently, the French administration was forced to increase the chiefs' allowances by 1,000% in 1943.[41] The Marist fathers tried to regulate the morals of the Uvean population, but romantic and sexual relationships developed between the GIs and Wallisian women.[42] Several mixed-race children were born from these unions.[42] After the American victory at Guadalcanal, the strategic interest in Polynesia diminished, and in February 1944, the dismantling and evacuation of American bases in Samoa and Wallis began.[37] The soldiers left Uvea.[43][44] By March, only 300 soldiers remained, and by June 1944, only twelve Americans were still on Uvea.[42] In April 1946, the last Americans departed from Wallis.[45] The period of wealth and extravagance ended as abruptly as it had begun. The Wallisians faced economic difficulties: subsistence farming had been neglected, coconut plantations were abandoned due to the lack of copra exports, and poultry populations were threatened with extinction. Even the lagoon had been damaged by blast fishing.[46] The population had to return to work. Futuna, on the other hand, was not occupied by the Americans and largely remained unaffected by these changes, suffering from isolation during the war.[16] End of the Protectorate (1946-1961)Economic, Social, and Political ChangesFollowing the American experience, “the balance of power was disrupted:”[47] between 1945 and 1950, the Kingdom of Uvea saw three kings (Leone Manikitoga, Pelenato Fuluhea, and Kapeliele Tufele). On December 22, 1953, a new succession crisis erupted, fueled by disagreements between the king, the administration, and the mission. Aloisia Brial was appointed Queen of Uvea.[47] Her reign was marked by political instability: the queen, considered overly authoritarian, faced opposition from her chieftaincy. In 1957, she was outvoted by the royal council but refused to abdicate. Tensions peaked when the district of Mu’a nearly seceded. The queen eventually resigned on September 12, 1958,[47] and after difficult negotiations, Tomasi Kulimoetoke II succeeded her on March 12, 1959, successfully asserting his authority.[47] In Futuna, political instability was even greater, with frequent changes of kings in the kingdoms of Alo and Sigave. The Catholic mission, represented by Father Cantala, retained significant power, although it largely stayed out of Futunian political disputes.[48] For example, in 1952, villages in Alo clashed over the succession of the Tu’i Agaifo.[48] During the 1950s, maritime and then air links were established between Wallis and New Caledonia, infrastructures were built, and local civil servants were recruited.[49] The post-World War II era was a period of economic crisis: the production of copra, the archipelago’s only commercial crop, collapsed in Wallis, forcing the population to return to subsistence farming. Meanwhile, the population continued to grow, and the youth, influenced by contact with Americans, aspired to a new way of life. Consequently, from 1974 onward, significant emigration developed toward French territories in the Pacific, such as the New Hebrides and New Caledonia. Most emigrants were young men. Religious and customary authorities supervised this labor migration, and the diaspora became more structured. By 1956, Wallisians and Futunians in New Caledonia numbered 1,200 people, with clergy and representatives from the chieftaincies of each kingdom. They were valued for their hard work and loyalty to France. However, “these migrations were regularly hindered by the status of Wallisians and Futunians, who came from a ‘protected country’ under France’s rule but lacked the advantages of a sovereign state or the privileges of a territory within the French Union.”[50] According to Frédéric Angleviel, the protectorate had become “anachronistic” and was undergoing “a long agony.”[51] The integration of Wallis and Futuna as a French overseas territory was driven by economic imperatives to facilitate migration.[50] Referendum and Change of Status (1959-1961)In 1958, the kings of Uvea, Alo, and Sigave petitioned the President of the French Republic (Charles de Gaulle) for Wallis and Futuna to be fully integrated into the Republic while preserving its unique characteristics: customary law for civil matters, land management by customary authorities, and maintaining Catholic education provided by the mission. An agreement was signed by the Minister of Overseas France, Jacques Soustelle, on October 5, 1959,[52] and a referendum was held on December 27, 1959. Over 94% of Wallisians and Futunians voted in favor.[52] Following the referendum results, a provisional assembly was established on February 17, 1960, bringing together the political, customary, and religious authorities of the three islands. This assembly drafted a bill, which was subsequently ratified by the French parliament on July 29, 1961, officially granting Wallis and Futuna the status of a French overseas territory. After 74 years, the protectorate came to an end.[50] AdministrationIn Wallis, governance relies on a delicate balance between customary authorities (the Lavelua and traditional chiefs), the clergy, the small French administration, and a handful of merchants. Tensions often run high, and political crises are frequent. Until the arrival of Resident Viala in 1905, the protectorate remained quite unstable.[53] In contrast, Futuna experienced more pronounced struggles between the kingdoms of Alo and Sigave, compounded by the absence of a French administrative presence. Customary AuthoritiesSocial and political dynamics in Wallisian and Futunian societies are primarily shaped by customary authorities (kings, district chiefs, and village chiefs). Anthropologist Sophie Chave-Dartoen notes that "the organization of Wallisian society is rooted in an intimate relationship between people and the land inherited from their ancestors." Leadership roles within certain families, particularly the titles of customary leaders ('aliki), are passed down based on both individual merit and familial ties:[10] "The titleholder must prove themselves." If disputes or conflicts arise, the bond with ancestors and God is considered broken, and the titleholder can be removed by their peers.[10] Each village is led by a chief (pule kolo), to whom the residents of a household ('api) pledge allegiance, providing services during customary ceremonies and participating in collective labor (fatogia). Above them are district chiefs (faipule) of Hihifo, Mu'a, and Hahake, and at the top is the supreme chief ('aliki hau), known as the Lavelua or "king" in English. The Lavelua presides over all religious and civil ceremonies and serves as the guardian of the primary forest—key to fertility—and the central shrubland, exploited during famines. The Lavelua is also responsible for the well-being and survival of the fenua ("land") and ensures the inalienability of land.[10] In Wallis, the sovereign (Lavelua) is chosen by royal families, allowing power to rotate among different families.[54] However, the selection must be approved by the resident, often influenced by the mission's stance. During the protectorate, 16 kings and queens ruled Wallis, most for only a few years. In times of crisis, such as in 1933, multiple Lavelua succeeded one another within months. From 1933 to 1941, Resident Jean Joseph David even suspended the election of a king.[48] In Futuna, against a backdrop of rivalry between the kingdoms of Alo and Sigave,[55] 20 kings ruled in Alo and 13 in Sigave between 1900 and 1960.[53] The administrative status of the indigenous population was unclear: "They required administrative authorization to leave the protectorate and a declaration of existence, as Wallisians and Futunians were neither citizens of an independent state nor subjects of the French Empire or later the French Union."[5] Mission CatholiqueThe Catholic clergy played a major role in shaping Wallis and Futuna’s society, exerting significant influence: “The superiors of the two missions, confessors to the great chiefs themselves, were the primary inspirers of Wallis and Futuna’s internal politics.”[5] Bishop Pierre Bataillon succeeded in transforming Wallis into a true insular theocracy, and his successors maintained this strong influence.[56] Religious festivals structured the calendar, and attending mass was mandatory. Despite this dominance, missionaries did not dismantle pre-Christian culture; instead, they carefully preserved customary practices, integrating them with Christianity. Scholars Dominique Pechberty and Epifania Toa describe this as a genuine syncretism,[57][note 2] while Frédéric Angleviel uses the term “inculturation.”[49]  In 1871, Queen Amelia Tokagahahau enacted the Code of Wallis (Tohi fono o Uvea). Drafted by Bishop Pierre Bataillon, this legislative text, written in Wallisian, precisely defined the composition of the chieftainship and established the king as the sole supreme leader. The king was responsible for appointing customary ministers, whose roles and titles—Kivalu, Mahe, Kulitea, Ulu'imonua, Fotuatamai, and Mukoifenua[58]—were specified in the code. The king also named district and village chiefs.[59] Similar codes were created by Marist priests for the two Futunan kingdoms[60] and amended in 1954 and 1960.[61] With the advent of Christianity, the Christian God became the supreme authority above the king. This led to the idea of a secular power dominated by a reference 'aliki (king), who himself was subject to God’s will. God, referred to as the 'Aliki of ultimate authority, was represented on Earth by the clergy.[10] In 1937, the Apostolic Vicariate of Wallis and Futuna was established, creating an autonomous diocese independent from Tonga. Alexandre Poncet was appointed its first bishop, becoming a key figure in the mission. The relationship between the mission and the French residency was complex. On the one hand, missionaries sought to shield the islands from secular influences deemed dangerous. On the other, French residents often criticized the clergy’s influence over the population. However, as Frédéric Angleviel noted, “The residency generally sought to maintain good relations with the mission, which was a key element of local life.”[49] The construction of infrastructure in the 1950s, such as schools and dispensaries, was positively received by the clergy. “The mission was favorable to anything that could improve the lives of its faithful, as long as Christian morality was upheld.”[61] In Futuna, the Marists maintained a particularly strong influence in the absence of a French administration.[61] Administration FrançaiseThe French administration represented the third source of authority in Wallis and Futuna but wielded limited influence. The protectorate was overseen by a resident, tasked with maintaining public order, advising the kings, and managing the budget.[23] However, in a society characterized by a system of gift and counter-gift exchanges—where monetary transactions were minimal—the assertion of power relied on the distribution of conspicuous goods (mats, pigs, etc.) during significant customary ceremonies (katoaga). Consequently, the resident's power was restricted to advisory roles and overseeing the small expatriate population of about twenty people, primarily missionaries and merchants.[5] The resident was supported by a chancellor and a radio operator, responsible for external communication, especially with New Caledonia.[51]  In the early 1930s, Alexis Bernast,[62] who held this post, became integrated into Wallisian society and played a role in local affairs. In 1906, an agreement with the Lavelua required the resident to also serve as a physician, as part of the colonial health service.[23] Residents typically stayed for about four years, contrasting with the Catholic mission’s long-term presence.[53] The resident lived on Wallis with the chancellor and visited Futuna only a few days each year, leaving the Futunians relatively autonomous but neglected in times of need.[16] Due to limited human resources, the resident often delegated responsibilities to a missionary, effectively making the clergyman the island's sole official representative.[5] This arrangement persisted until the late 1950s, with the administration establishing a permanent presence on Futuna only in 1959.[16] The protectorate's funding came from the Ministry of the Navy and Colonies. In addition to taxes on commercial transactions, philately became a significant revenue source. Between 1928 and 1939, stamp sales accounted for half of the protectorate's income, according to Frédéric Angleviel.[63] While some residents, like Jean-Joseph David, highlighted their achievements, criticism of the French presence was widespread. In 1947, the Governor of New Caledonia, Georges Parisot, condemned the colonial administration: “Our system of administration in this archipelago is outdated. [...] What have we done for these natives in sixty years of the protectorate? Absolutely nothing, except for a hospital where rain seeps through the roof and that is very often without medication.”[62] Similarly, historian Jean-Claude Roux described the colonial administration as “a mere shadow, lacking resources and direction, forced to improvise in every crisis.”[62] World War II marked a turning point for the French administration. In 1942, an independent police force was established, signaling a strengthening of the residency's role. However, the overall administrative impact remained limited compared to other influences, such as the Catholic mission and traditional authorities.[49] EconomyFood Agriculture and Local Trade The inhabitants of Wallis and Futuna rely on subsistence fishing within the lagoon and the cultivation of staples such as taro, bananas, yams, and kapé. Pig farming is primarily reserved for traditional ceremonies like the katoaga. Polynesian societies operate under a system of gift and counter-gift, with minimal monetary exchanges.[1] The only export crop is coconuts, processed into copra.[16] In 1867, a new drying technique for green copra was introduced to Wallis from Samoa by the German Théodore Weber. French residents promoted the island's development around this monoculture, expanding coconut plantations. However, the industry collapsed in the 1930s due to an oryctes beetle invasion and the global economic downturn caused by the Great Depression.[16] The arrival of sailors and traders in the 19th century brought currency to the region. Initially, the local population used currencies such as the Chilean peso, the English pound, and the dollar. Despite efforts by French residents and merchants,[64] the French franc was not widely adopted until its mandatory implementation in 1931, which economically integrated the archipelago with Nouméa.[64] In 1945, the Pacific Franc (CFP) was introduced and remains the currency in use. Currency became integrated into ceremonial exchanges, supplementing the traditional offerings of pigs and mats with envelopes of money.[10]  Additionally, prominent merchant families, like the Brials, played significant roles in local commerce. For example, Julien Brial, a French merchant married to Aloisia Brial from a noble Wallisian family, significantly influenced both economic and political life on the island.[65] In 1910, the Australian company Burns Philp established a presence in Wallis, strengthening its foothold in the South Pacific. Chinese companies also briefly engaged in copra trading in 1912[66] but departed shortly after.[67] Relations between merchants and local authorities were often strained. According to Jean-Claude Roux, while merchants sought profitable ventures, islanders aimed to extract maximum benefits from these "foreigners."[68] In the 1920s, Chinese merchants allied with Julien Brial to form a monopoly, reducing wages for Wallisian workers. This led customary authorities to denounce the situation.[69] During this period, traditional kings occasionally imposed tapu (prohibitions) on copra to counter merchant abuses, a practice especially common in Futuna.[70] World War II significantly disrupted the economic balance of Uvea (Wallis). After a period of total isolation, which led to shortages of basic goods and a return to subsistence agriculture, the arrival of American troops in 1942 transformed the local economy. With high purchasing power, American soldiers employed many Wallisians, boosting incomes and altering political dynamics. In response, the resident had to increase the indemnities paid to customary chiefs by 1,000% in 1943.[41] Post-war, funds from the Ministry of Overseas France increased, allowing for the construction of roads, dispensaries, and subsidies for Catholic schools.[5] However, the American departure left the Wallisian economy in crisis. Although copra exports resumed in 1948, they steadily declined throughout the 1950s.[71] Burns Philp left the archipelago after the war, replaced by the Nouméa-based Lavoix company in 1947.[67] The Brial family remained influential, with Victor-Emmanuel Brial managing the Wallis trading post, succeeded by his brothers Benjamin in Wallis and Cyprien in Futuna.[47] In 1950, Ballande, a company from New Caledonia, established a branch in Wallis, becoming the second French commercial enterprise on the island.[67] Following World War II, New Caledonian companies began recruiting workers from Wallis and Futuna, initiating labor migration that became an essential feature of the island's economic landscape. This emigration helped sustain local households but also marked a significant shift in the island's economic structure.[4] TaxationAt the beginning of the protectorate, administrative resources were scarce, with expenditures limited to the resident’s indemnity. Without a budget, no projects could be undertaken. The protectorate was financed by New Caledonia, but the issue of a local tax soon arose: "The fiscal problem was a constant concern of the colonial administration."[72] In 1906, Viala attempted to introduce a personal tax but faced opposition from the mission (largely funded by donations from the faithful) and the Lavelua.[73] After negotiations, the king agreed to pay an annual “voluntary contribution” of 900 Chilean pesos in exchange for the presence of a resident doctor on the island.[74] However, an increase in the export tax on copra was rejected by the island’s principal merchant.[74] In April 1907, a cyclone hit Futuna, and with no commercial revenue, the inhabitants were unable to pay their fiscal contributions.[74] In 1911, while Resident Brochard was away from the territory, the Lavelua refused to pay his annual contribution.[75] In April 1912, Brochard returned and gathered support from customary chiefs who favored the introduction of a poll tax. However, this tax was only implemented during World War I, partly due to the intervention of Bishop Joseph Félix Blanc, who convinced the king in a period of national unity.[76] The tax was collected in English pounds, which was affected by exchange rates (a 1928 law quintupled the value of one English pound). In 1930, the oryctes pest devastated coconut plantations in Wallis, causing a collapse in copra production and making the tax much harder to collect.[77] As a result, the tax was reduced to 40 francs in 1934.[72] Languages and EducationThe Indigenous populations of Wallis and Futuna speak their vernacular Polynesian languages: Wallisian in Wallis and Futunan in Futuna. External interactions, particularly trade with Fiji, were conducted primarily in a pidginized form of English. Many words referring to European goods and techniques entered the local languages (e.g., mape for “map,” suka for “sugar,” sitima for “motorboat” from steamer, pepa for “paper,” and motoka for “car” from motor-car).[78][79] This Pidgin English remained in use until the 1930s when the copra crisis ended trade relations with neighboring English-speaking territories. English saw a resurgence during World War II due to the American presence.[78] From their arrival, missionaries took charge of education. They aimed to train an indigenous clergy, teaching reading, mathematics, and ecclesiastical Latin in the local languages. Religious texts in Wallisian and Futunian were printed starting in 1843, incorporating numerous terms from ecclesiastical Latin.[79] In 1873, the missionaries established a seminary in Lano to train Catholic priests from Oceania. For sixty years, seminarians from Tonga, Samoa, Niue, Futuna, and Wallis received instruction entirely in Wallisian.[78] Missionaries often acted as interpreters for French authorities, granting them considerable influence,[80] as the residents typically did not speak Wallisian.[78] French was not taught at all, as the Marists saw little value in it. This quickly became a point of contention with the administration, which accused the clergy of depriving the local population of the French language. For a brief period, some Marists were sent by Bishop Olier to teach French, but this effort ended in 1911. The first public school was opened in 1933 in Mata-Utu by Resident Brochard after difficult negotiations. The agreement between the mission and the resident stipulated that the school’s schedule, exclusively dedicated to teaching French, would not interfere with the missionaries’ Catholic schools. The clergy also insisted that the teacher be a practicing Catholic. However, the school closed a few months later due to a lack of students.[78] Consequently, French remained virtually absent from the linguistic landscape throughout the first half of the 20th century.[78] Legacy and PerceptionPierre-Yves Le Meur and Valelia Muni Toke note that by the 2010s, the era of the protectorate, "though not without instances of colonial violence", seems to have been largely forgotten by the inhabitants. Instead, greater emphasis is placed on the subsequent status as a territory and then an overseas collectivity, "seen as a symbol of partnership with France rather than subordination." This perception is particularly significant because, in the 2010s, the French government expressed interest in exploiting mineral resources in the seabed within Wallis and Futuna's exclusive economic zone. This sparked strong opposition among the local population, who viewed it as a form of colonial imposition, overshadowing the image of France as a protective power.[81] See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||