|

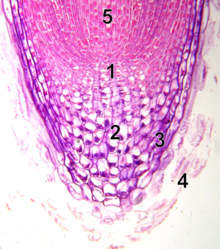

Primary growthPrimary growth in plants is growth that takes place from the tips of roots or shoots. It leads to lengthening of roots and stems and sets the stage for organ formation. It is distinguished from secondary growth that leads to widening. Plant growth takes place in well defined plant locations. Specifically, the cell division and differentiation needed for growth occurs in specialized structures called meristems.[1][2] These consist of undifferentiated cells (meristematic cells) capable of cell division. Cells in the meristem can develop into all the other tissues and organs that occur in plants. These cells continue to divide until they differentiate and then lose the ability to divide. Thus, the meristems produce all the cells used for plant growth and function.[3] At the tip of each stem and root, an apical meristem adds cells to their length, resulting in the elongation of both. Examples of primary growth are the rapid lengthening growth of seedlings after they emerge from the soil and the penetration of roots deep into the soil.[4] Furthermore, all plant organs arise ultimately from cell divisions in the apical meristems, followed by cell expansion and differentiation.[1] In contrast, a growth process that involves thickening of stems takes place within lateral meristems that are located throughout the length of the stems. The lateral meristems of larger plants also extend into the roots. This thickening is secondary growth and is needed to give mechanical support and stability to the plant.[4] The functions of a plant's growing tips – its apical (or primary) meristems – include: lengthening through cell division and elongation; organising the development of leaves along the stem; creating platforms for the eventual development of branches along the stem;[4] laying the groundwork for organ formation by providing a stock of undifferentiated or incompletely differentiated cells[5] that later develop into fully differentiated cells, thereby ultimately allowing the "spatial deployment off both arial and underground organs."[1] Primary growth in stems In stems, primary growth occurs in the apical bud (the one on the tips of stems) and not in axillary buds (primary buds at locations of side branching). This results from apical dominance, which prevents the growth of axillary buds that form along the sides of branches and stems. Auxin (a plant hormone) produced in the apical bud inhibits the growth of axillary buds. However, if the apical bud is removed or damaged, the axillary buds begin to grow.[4] These axillary buds have developed through evolution as a form of botanical risk management – they give the plant a means to continue to grow in the face of environmental hazards. When gardeners prune the tops of branches in order to obtain a bushier plant, they are using this feature of primary growth in plants. By eliminating the apical bud, they force the axillary buds to start growing, causing the plant to emit new stems.[4][5] Primary growth in roots Evolution has provided plants with a way of dealing with the injuries created as the root system burrows its way through soil that contain objects that injure the root buds. The tip of the root is protected by a root cap that is continuously sloughed off and replaced because it gets damaged as it pushes through the soil. Cellular division via mitosis takes place at the very tip of the root cap. The newly created cells then begin a stretching process of cellular elongation, thereby adding length to the root. Finally, the cells undergo a process of cellular differentiation that converts them into the components of dermal, vascular or ground tissues.[5][6] Plant morphology and functionBy laying the groundwork for organ differentiation and because of its role in plant growth, primary growth – coordinated with the secondary growth process – largely determines the morphology and functioning of plants. The question of how the biochemical pathways underpinning this process are regulated and coordinated is the subject of ongoing research. This research sheds light on the nature and timing of gene expression and of hormonal regulation in this process, though their roles are still not completely understood.[1][2] See alsoReferences

|