|

Preseli Mountains

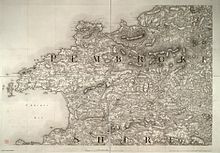

The Preseli Mountains (English: /prəˈsɛli/, prə-SEL-ee; Welsh: Mynyddoedd y Preseli or Y Preselau), also known as the Preseli Hills, or just the Preselis, is a range of hills in western Wales, mostly within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park and entirely within the county of Pembrokeshire. The range stretches from the proximity of Newport in the west to Crymych in the east, some 13 miles (21 km) in extent. The highest point at 1,759 feet (536 m) above sea level is Foel Cwmcerwyn. The ancient 8 miles (13 km) of track along the top of the range is known as the Golden Road.[1][2] The Preselis have a diverse ecosystem, many prehistoric sites, and are a popular tourist destination. There are scattered settlements and small villages; the uplands provide extensive unenclosed grazing, and the lower slopes are mainly enclosed pasture. Slate quarrying was once an important industry. More recently, igneous rock is being extracted. The Preselis have Special Area of Conservation status, and there are three sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs). Name variationsA peak is spelt Percelye on a 1578 parish map, and more recent maps show the range as Presely or Mynydd Prescelly. The etymology is unknown, but is likely to involve Welsh prys, meaning "wood, bush, copse".[3] A number of other peaks are shown on the 1578 map, but the only other named peak is Wrennyvaur (now Frenni Fawr). An 1819 Ordnance Survey Map refers to the range as Precelly Mountain (singular).[4][5] An 1833 publication stated: the ancient Welsh name...is Preswylva, signifying "a place of residence",[6] but does not cite any evidence. 21st century maps show the range as Mynydd Preseli.[7] Geology

The hills are formed largely from the Ordovician age marine mudstones and siltstones of the Penmaen Dewi Shales and Aber Mawr Shale formations which have been intruded by microgabbro (otherwise known as dolerite or diabase) of Ordovician age. The former slate quarries at Rosebush on the southern edge of the hills worked the Aber Mawr Formation rocks whilst it is the dolerite tors of Carnmenyn which have been postulated, amongst other localities, as the source of the Stonehenge ‘bluestones’. In contrast Foel Drygarn towards the eastern end of the range is formed from tuffs and lavas of the Fishguard Volcanic Group. Further east is Frenni Fawr which is formed from mudstones and sandstones of the Nantmel Mudstone Formation of late Ordovician Ashgill age. The sedimentary rocks dip generally northwards and are cut by numerous geological faults. Cwm Gwaun is a major glacial meltwater channel which divides the northern tops such as Mynydd Carningli from the main mass of the hills.[8] GeographyThe hills, much of which are unenclosed moorland or low-grade grazing with areas of bog, are surrounded by farmland and active or deserted farms. Field boundaries tend to be earth banks topped with fencing and stock-resistant plants such as gorse.[9] Rosebush Reservoir, one of only two reservoirs in Pembrokeshire, supplies water to southern Pembrokeshire and is a brown trout fishery[10] located on the southern slopes of the range near the village of Rosebush. To the south is Llys y Fran reservoir. There are no natural lakes in the hills, but a number of rivers, including the Gwaun, Nevern, Syfynwy and Tâf have their sources in the range.[7] PeaksThe principal peak at 1,759 feet (536 m) above sea level is Foel Cwmcerwyn. There are 14 other peaks over 980 feet (300 m) of which three exceed 1,300 feet (400 m).[5]

SettlementsVillages and other settlements within the range include Blaenffos, Brynberian, Crosswell, Crymych, Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross, Glandy Cross, Mynachlog-ddu, New Inn, Pentre Galar, Puncheston, Maenclochog, Rosebush and Tafarn-y-Bwlch. The only town in the Preseli area is Newport, at the foot of the Carningli-Dinas upland in the northwest of the range.[5] Natural history and land useThe Preselis provide hill grazing for much of the year and there is some forestry. As well as features of interest to geologists and archaeologists, the hills have a wide variety of bird, insect and plant life. There are three sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs): Carn Ingli and Waun Fawr (biological), and Cwm Dewi (geological). The Preseli transmitting station mast, erected in 1962, stands on Crugiau Dwy near the hamlet of Pentre Galar. To the south of Crugiau Dwy is the extensively quarried hill Carn Wen (Garnwen Quarry) which was still actively extracting igneous rock in 2018.[11] The Preselis have Special Area of Conservation status; the citation states that the area is "... exceptional in Wales for the combination of upland and lowland features..." Numerous scarce plant and insect species exist in the hills.[12] For example, they are an important UK site for the rare Southern damselfly, Coenagrion mercuriale,[13] where efforts to restore habitat were underway in 2015[14] and reported in 2020 to have been a success.[15] Communications and accessOne major road, the A478, crosses the eastern end of the range, reaching a height of 248 metres (814 ft). Two B-class roads, intersecting at New Inn, cross the hills: the B4313 NW-SE, reaching 278 metres (912 ft) and the B4329 NE-SW, reaching 404 metres (1,325 ft) at Bwlch-gwynt (translation: windy gap). These, and a number of other minor roads and lanes, provide scenic routes popular with motoring, cycling and walking tourists. The A487 road skirts the western end of the range, near Newport.[7] Cattle grids prevent egress of grazing stock from unenclosed areas of the hills. The Preselis are popular with walkers wishing to follow prehistoric trails,[16] with walks varying from easy to long-distance. The larger part of the hills is designated under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 as 'open country' thereby enabling walkers the 'freedom to roam' across unenclosed land, subject to certain restrictions. An east-west bridleway which runs the length of the main massif (known as Flemings' Way[17] or the Golden Road[1]), together with spurs to north and south, gives access to mountain bikers and horseriders.[18] There are cycle trails.[19] Paragliding is not permitted without the consent of the land owners, who in 2014 collectively agreed not to allow it.[20] Other features Castell Henllys, on the A487 road between Eglwyswrw and Felindre Farchog is a reconstructed Iron Age settlement, illustrating what life may have been like in those times.[21] PrehistoryThe Preselis are dotted with prehistoric remains, including evidence of Neolithic settlement. More were revealed in an aerial survey during the 2018 heatwave.[22] Samuel Lewis's A Topographical Dictionary of Wales published in 1833 said of Maenclochog parish:

Pollen analysis suggests that the hills were once forested but the forests had been cleared by the late Bronze Age.[12] Bluestones In 1923 the petrologist Herbert Henry Thomas proposed that bluestone from the hills corresponded to that used to build the inner circle of Stonehenge,[24] and later geologists suggested that Carn Menyn (formerly called Carn Meini) was one of the bluestone sources.[25] Recent geological work has shown this theory to be incorrect.[26] It is now thought that the bluestones at Stonehenge and fragments of bluestone found in the Stonehenge "debitage" have come from multiple sources on the northern flanks of the hills,[27] such as at Craig Rhos-y-felin.[28] Advanced details of a recent contribution to the puzzle of the precise origin of the Stonehenge bluestones were published by the BBC in November 2013.[29] Others theorise that bluestone from the area was deposited close to Stonehenge by glaciation.[30] More detailed discussions on the bluestone topic can be found in the Stonehenge, Theories about Stonehenge and Carn Menyn articles. Investigations published in 2021 suggested a link between Waun Mawn (see below) and the Stonehenge bluestones,[31] but this was disputed in a 2024 study.[32][33] Individual sites   The Preselis are rich in sacred and prehistoric sites,[9] many of which are marked on Ordnance Survey maps.[7] They include burial chambers, tumuli, hill forts, hut circles, stone circles, henges, standing stones and other prehistoric remains. These sites are spread across a number of communities that share parts of the Preseli range. Dyfed Archaeological Trust has produced extensive notes on the mountain range and surrounding features and villages.[9][17] Some of the more notable are:

Others include:

HistorySlate quarrying was once an important industry in the Preselis; the former quarries, worked for much of the 19th century, can still be seen in a number of locations such as Rosebush.[51] Preseli slate was not of roofing quality, but its density made it ideal for machining for building and crafts.[52] Most quarries had closed by the 1930s[53] but there is a workshop at Llangolman where slate is still used to make a variety of craft items. During the Second World War, the War Office used the Preselis extensively for training exercises by British and American air and ground forces.[54][55] Its proposed continued use after the war was the subject of a two-year ultimately successful protest by local leaders.[56] The success of the protest was commemorated 60 years on, in 2009, with a plaque at each end of the Golden Road: one at the foot of Foel Drygarn near Mynachlog-ddu, and another near the B4329 at Bwlch-gwynt.[57] In 2000, Terry Breverton, a lecturer at Cardiff University, in promoting a book he had published, suggested that the rock star Elvis Presley's ancestors came from the Preselis and may have had links to a chapel at St Elvis.[58][59] References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Preseli Hills. |