|

Pirna

Pirna (German: [ˈpɪʁna] ; Upper Sorbian: Pěrno, pronounced [ˈpʲɪʁnɔ]) is a town in Saxony, Germany and capital of the administrative district Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge. The town's population is over 37,000. Pirna is located near Dresden and is an important district town as well as a Große Kreisstadt. GeographyGeographical locationPirna is located in the vicinity of the Sandstone Mountains in the upper Elbe valley, where two nearby tributaries, Wesenitz from the north and Gottleuba from the south, flow into the Elbe. It is also called the "gate to the Saxon Switzerland" (Ger: Tor zur Sächsischen Schweiz). The Saxon wine region (Ger: Sächsische Weinstraße), which was established in 1992, stretches from Pirna via Pillnitz, Dresden, and Meissen to Diesbar-Seußlitz. Neighboring municipalitiesPirna is located southeast of Dresden. Neighboring municipalities are Bad Gottleuba-Berggießhübel (town), Bahretal, Dohma, Dohna (town), Dürrröhrsdorf-Dittersbach, Heidenau (town), Königstein (town), Lohmen, Stadt Wehlen (town), and Struppen. Names

LanguageThe regiolect spoken in Pirna is Südostmeißenisch, which is part of the Upper Saxon German group of regiolects. HistoryHistorical affiliations

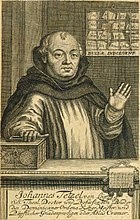

Stone AgeTools made of flint from the late Paleolithic (about 12,000-8000 BC), at the end of the last ice age, are evidence for the earliest human settlement in the area. Later on, people belonging to the Linear Pottery culture, who farmed grain and cattle, lived here during the Neolithic (5500-4000 BC) because of a good climate and Loess soil. Around 600 AD a Slavic group called the Sorbs, who were fishermen and farmers, succeeded the Germanic tribes in the Elbe Valley, who had lived in the area for a couple of centuries from the 4th century BC on. The name Pirna derives from the Sorbian phrase, na pernem, meaning on the hard (stone) and is also related to the Slavic deity Perun, whose cult was present in all Slavic and Baltic territories. The representation of a pear tree in the coat of arms was a later cryptic representation of the Perun cult, covered up by a fanciful, German-language notion about the town's name ("pear" is Birne in German, which sounds rather like "Pirna" Latin: "Pyrus"). Middle AgesWith the conquest of the Slavic communities and the founding of the Mark by the Germans (Henry the Fowler founded the castle of Meissen in 929), settlement in the Pirna area is again verifiable. The castle in Pirna, which was mentioned for the first time in 1269, probably already existed in the 11th century. In the context of the second Eastern German colonization the town was founded by Henry III, Margrave of Meissen. The streets are aligned from east to west and north to south forming a chessboard-like system. Only the streets east of the church are not aligned in this form, caused by the nearby Burgberg. In 1233, Pirna was mentioned officially for the first time in a document. In 1293, King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia acquired both town and castle from the Bishop of Meissen. Therefore Pirna belonged to Bohemia until 1405. Early Modern timesIn 1502, the construction of the new church was begun under Meister Peter Ulrich von Pirna. With the introduction of the Reformation into Saxony in 1539, Anton Lauterbach, a friend of Martin Luther, became pastor and superintendent. In 1544 the strategically important castle was upgraded to a fortress by Maurice, Elector of Saxony. Three years later, it withstood the siege by elector John Frederick, Elector of Saxony in the Schmalkaldic War. On April 23, 1639, the town was invaded by Swedish troops under the commander in chief of the Swedish army, Johan Banér. During the five-month long siege of the fortress, which was in the end futile, the town was greatly devastated. About 600 people were murdered (Pirnaisches Elend, lit. "Misery of Pirna").[4] In around 1670, based upon recent military developments, the Sonnenstein fortress was built. Only the powerful stonework still exists today.[clarification needed] In 1707, Pirna had debts that related to the Great Northern War of more than 100,000 Thalers. Prussian Pirna  On August 29, 1756, the small Saxon army fled before the Prussians, who had invaded without declaring war, to the levels between Königstein Fortress and Sonnenstein Castle and capitulated there on October 16, two days after Sonnenstein surrendered. In 1758, Austrian troops and the Imperial Army besieged the fortress. Napoleonic PirnaA Kattundruck manufactory for cotton printing opened as the first of its kind in 1774. In 1811 the physician Ernst Gottlob Pienitz opened a very large mental hospital in Castle Sonnenstein. But when on September 14, 1813, French troops occupied the Sonnenstein, they forced the evacuation of 275 patients, seized supplies and tore the roof trusses out to remove a fire threat. In September 1813, emperor Napoleon temporarily lived at the Marienhaus, located at the market. Until Dresden's surrender on November 11 the French defended the fortress. Only in February 1814 the hospital for the mentally ill was able to open again. Industrial revolution, Imperial Germany and the Weimar RepublicIn 1837, steamship travel began on the upper Elbe. A few years later, in 1848, a railway line connecting Dresden and Pirna opened. In 1880, the first section of the Sekundärbahn-type railway line from Pirna to Gottleuba, the Gottleuba Valley railway was opened. The line was closed in 1976. In 1894, another railway line opened was the Pirna–Großcotta railway, connecting Pirna with the Lohmgrund, a major location of Saxonian sandstone quarries. It closed in 1999. Pirna became an industrial town in 1862 with the building of factories. Mechanical engineering, glass, cellulose and rayon production also expanded. In 1875, the sandstone Elbbrücke was completed. During the First World War Pirna became a garrison and the engineer battalions 12 and 5 of the Royal Saxon field artillery regiment No. 64 were billeted on Rottwerndorfer Straße. In 1922/23, the town incorporated several municipalities including Posta, Niedervogelgesang, Obervogelgesang, Copitz, Hinterjessen, Neundorf, Zuschendorf, Rottwerndorf and Zehista. The population totaled about 30,000 inhabitants. Nazi Germany and World War II  From early 1940 until end of June 1942, a part of the large mental asylum within Sonnenstein Castle was converted into a euthanasia killing center: the Sonnenstein Nazi Death Institute. It was a testing ground for initial development of certain methods, later generally adopted and refined for usage associated with the Final Solution. A gas chamber and crematorium were installed in the cellar of the former men's sanitary (building C 16). A high brick-wall on two sides of the complex shielded it from outside view. Four buildings were located inside this brick-wall shielding. They were used as offices, living rooms for the personnel, etc. Sleeping quarters for the men responsible for incinerating the bodies were provided in the attic of building C 16. It is possible that other sections of the buildings were also used by Action T4. From end of June 1940 until September 1942, approximately 15,000 persons were killed in the scope of the mass murder by involuntary euthanasia program and the Sonderbehandlung Action 14f13. The personnel list consisted of about 100 persons. One third of them were reassigned to the extermination camps in occupied Poland, because of their recent experiences in deception, killing, gassing and incinerating of people. There, they were trained by the detachments responsible for organized killing in camps like Treblinka. These killings ceased after pressure was exerted on the authorities by the local population. During August and September 1942, the Sonnenstein killing center was closed and incriminating installations such as gas chamber installations and crematorium ovens dismantled. After October 1942, the buildings were used as a military hospital. This part of the town's history was largely unrecognized in Germany until 1989, but after the regime change which was happening during this period, efforts to remember these catastrophic events began. In June 2000 a permanent exhibition opened, and today a small plaque at the base of Sonnenstein Castle together with the Sonnenstein Memorial provide remembrance.[5] At the end of the war several air raids took place mainly targeting the railway station in Pirna and the Děčín–Dresden Railway. The air raid on April 19, 1945, destroyed all railway tracks and also the bridge over the Elbe.[6] Though there were only strategic targets most of the over 200 dead were civilians.[7] During the GDR  During the existence of the GDR and its economic model, a so-called planned economy, people mostly worked in publicly owned enterprises:

Among other things, Pirna 014 turbines for the 152 jet aircraft developed in the GDR were built at VEB Strömungsmaschinen. All these businesses did not continue to exist for long after reunification, because they were not competitive. The Elbe river was heavily polluted by industry wastewater, especially from the cellulose fiber factory; swimming in the river was no longer possible without dangers to health. In the mid-1980s, around 1,700 un-renovated apartments stood empty in Pirna, 400 of them in the old town. Individual particularly badly dilapidated houses were demolished in the period that followed, for example a house on the southeast corner of the market square and the so-called Kern’sche Haus in the Burgstraße. When in 1989 the Teufelserkerhaus was to be torn down as part of demolition measures in the old town, public demonstrations happened with people shouting “Save Pirna”. From this circle, the Kuratorium Altstadt (literally Old Town Board of Trustees) was formed, which provided outstanding services during the period of reconstruction which began after the fall of the Berlin Wall. After German Re-unification  The de-industrialization in the course of German reunification, unprecedented in the history of the town, was formative. The immediate transition to a market economy led to the shutdown of a considerable part of the structure-determining industrial companies. In the three largest factories of silk, fluid machinery and cellulose fiber alone, more than 5,000 jobs were lost by the mid-1990s as a result of closure and liquidation by the Treuhandanstalt. It is true that new jobs were created in the service industry; however, these alone could not compensate for such a huge loss. The establishment of new jobs in the manufacturing industry turned out to be difficult, not least because of the lack of a federal highway connection. The reconstruction of the inner town has been advanced considerably since the beginning of the 1990s with intensive funding from the urban development funding programs. In the meantime, over 90% of the 300 buildings in the historic old town have been renovated. The number of inhabitants in the redevelopment area of the old town has doubled since the end of the 1990s, from almost 1,000 to almost 2,000 (as of 2013). The market square and the surrounding alleys have developed into a district quite worth seeing with shops, bars and cafes, as well as other cultural offerings (including the Tom-Pauls-Theater). The renovation of the old town repeatedly brought historical features to light. During the renovation of a house on the market square, for example, an approx. 500-year-old wall painting was uncovered that shows a "wrong" type of wild animal hunting - animals hunting and devouring humans - and which, according to the Saxon State Office for Monument Protection, is unique in this form in Saxony. In addition, valuable wooden beam ceilings were exposed in numerous houses.  In August 2002, the town suffered great damage during the widespread flooding in Europe, reaching its apex on 16 August. Two factors greatly worsened the effect: First, the large earthen structure supporting the railway line acted as a dam, retaining the waters both longer and higher on the towns' side. Second, all the shop-fronts which had been renovated post-unification were practically all kind of sealed in terms of water-tightness: the floodwaters rose outside whilst the shops themselves stayed dry inside; but when reaching certain critical points, the weight of the water then suddenly destroyed these shop-fronts when the windows broke. Ironically, older "leaky" shopfronts did not suffer this fate, as the water built up height and thus pressure equally on both sides. Whilst international media mainly concentrated on the impact upon Dresden the impact upon Pirna was proportionately much worse. Schöna and Bad Schandau were also affected heavily. In July 2005, Pirna finally received federal highway access via its own connection, when a section from Dresden to Pirna of the Bundesautobahn 17 was completed. The extension to the Czech border was opened to traffic in December 2006. The inner town and the areas close to the Elbe in Pirna were again affected by severe flooding by the Elbe in June 2013, while still being severe, it failed to meet the record levels of the 2002 flood: The water level of the Elbe reached a height of 9.66 metres (31.7 ft) (2002: 10.58 metres (34.7 ft)). By June 5, 2013, around 7,700 people had to be evacuated, and about 1000 buildings were affected by the water. PoliticsThe mayor in Pirna is elected every seven years. Markus Ulbig (CDU) held this position from 2001 to 2009.[8] He was last confirmed in office on June 8, 2008 with 64.87 percent of the vote. Ulbig was appointed Saxon Interior Minister and the post went to the non-party mayor Christian Flörke. In January 2010 there were new elections in which Klaus-Peter Hanke (Free Voters) was elected with 60% in the second round. In 2017, Hanke was re-elected with 60.5% of the vote in the first round. In December 2023, Tim Lochner was elected Mayor of Prina. Lochner is independent of a party, but was nominated as a candidate by the right-wing party AfD. It is the first mayor of a city with more than 20,000 inhabitants to be appointed by the AfD.[9] Administrative incorporations Villages and other municipalities that were incorporated into Pirna:

PopulationChange of population (from 1960, all figures for December 31):

1 October 29 Culture Museums

Music

Art

TransportPirna station, on the Dresden S-Bahn and the Dresden to Prague railway, is located to the west of the town centre, and is the junction point for the line to Neustadt in Sachsen and Sebnitz. Besides the town's main station, it is also served by Obervogelgesang, Pirna-Copitz and Pirna-Copitz Nord stations. Pirna is also a stop for the Sächsische Dampfschiffahrt ships, including historic paddle steamers, operating on the Elbe between Dresden and the Czech border.[16][17] Local and regional bus services are operated by the Regionalverkehr Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge.[18] Twin towns – sister citiesNotable people

Honorary citizens

See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Pirna. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||