|

Phycosphere

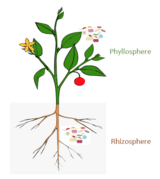

The phycosphere is a microscale mucus region that is rich in organic matter surrounding a phytoplankton cell. This area is high in nutrients due to extracellular waste from the phytoplankton cell and it has been suggested that bacteria inhabit this area to feed on these nutrients. This high nutrient environment creates a microbiome and a diverse food web for microbes such as bacteria and protists.[1] It has also been suggested that the bacterial assemblages within the phycosphere are species-specific and can vary depending on different environmental factors.[2] In terms of comparison, the phycosphere in phytoplankton has been suggested analogous to the rhizosphere in plants, which is the root zone important for nutrient recycling. Both plant roots and phytoplankton exude chemicals which alter their immediate surrounds drastically – including altering the pH and oxygen levels. In terms of community construction, chemotaxis is used in both environments in order to propagate the recruitment of microbes. In the rhizosphere, chemotaxis is used by the host – the plant – to mediate the motility of the soil which allows for microbial colonization. In the phycosphere, the phytoplankton release of specific chemical exudates elicits a response from bacterial symbionts who exhibit chemotaxis signaling, thereby enabling the recruitment of microbes and subsequent colonization. The interfaces also have a few similar microbes, chemicals, and metabolites involved in the host – symbiont interactions. This includes microbes such as Rhizobium, which in the phycospheres of green algae was found to be the foremost microbe when compared to other abundant community members. Chemicals such as dimethylsuloniopropionate (DMSP) and 2,3-dihydroxypropane-1-sulfonate (DHPS) and metabolites such as sugars and amino acids are implicated in the mechanisms of action of both microbiomes. Phytoplankton-bacteria interactionsThe microscale interactions between the phytoplankton and bacteria are complex. The phytoplankton-bacteria interactions have the potential to be parasitism, competition or mutualism. Interactions between phytoplankton and bacteria in the phycosphere could be potentially important in low-nutrient regions of the ocean and an example of mutualism. In marine ecosystems that are low in nutrients (i.e. oligotrophic regions of the oceans), it could be potentially beneficial for the phytoplankton to have remineralizing bacteria in the phycosphere for nutrient recycling. It has been suggested that while the bacterial activity may be low, the taxonomic diversity and nutritional diversity is high.[3] This can possibly suggest that the phytoplankton species may rely on a diverse array of bacterial interactions for recycled nutrients in these oligotrophic regions and the bacteria rely on organic matter surrounding the phycosphere for a source of food. However, bacterial-phytoplankton interactions in the phycosphere could be parasitic. In the same low nutrient oligotrophic regions of the ocean, phytoplankton that are nutrient stressed may not be able to produce this protective mucus layer or its associated antibiotics. The bacteria, who are also food stressed, could kill the phytoplankton and use it as a food substrate.[4] Also, bacteria metabolize the organic matter through aerobic respiration, which depletes oxygen from the water and can lower the pH of the water column. If enough organic matter is produced, the bacteria could potentially harm the phytoplankton by causing the water to become more acidic. (See also eutrophication). Examples of bacteria associated with phycosphereIn reality, the actual bacterial diversity of the phycosphere is extremely diverse and is dependent environmental factors, such as turbulence in the water (so the bacteria can attach to the mucus or the phytoplankton cell) or the concentrations of nutrients. Also, the bacteria tend to be highly specialized when associated with this region. Nevertheless, here are some examples of bacterium genera associated with the phycosphere.

See alsoReferences

5. Seymour, Justin R., et al. “Zooming in on the Phycosphere: the Ecological Interface for Phytoplankton–Bacteria Relationships.” Nature Microbiology, vol. 2, no. 7, 2017, pp. 1–13., doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.65. 6. Kim, B.-H., Ramanan, R., Cho, D.-H., Oh, H.-M., & Kim, H.-S. (2014). Role of Rhizobium, a plant growth promoting bacterium, in enhancing algal biomass through mutualistic interaction. Biomass and Bioenergy, 69, 95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.07.015 7. Geng, H., & Belas, R. (2010). Molecular mechanisms underlying roseobacter–phytoplankton symbioses. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 21(3), 332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.013 8. Ramanan, R., Kang, Z., Kim, B.-H., Cho, D.-H., Jin, L., Oh, H.-M., & Kim, H.-S. (2015). Phycosphere bacterial diversity in green algae reveals an apparent similarity across habitats. Algal Research, 8, 140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.003 9. Scharf, B. E., Hynes, M. F., & Alexandre, G. M. (2016). Chemotaxis signaling systems in model beneficial plant–bacteria associations. Plant Molecular Biology, 90(6), 549–559. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0432-4 |