|

Philo Vance

Philo Vance is a fictional amateur detective originally featured in 12 crime novels by S. S. Van Dine in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, Vance was immensely popular in books, films, and radio. He was portrayed as a stylish—even foppish—dandy, a New York bon vivant possessing a highly intellectual bent. "S. S. Van Dine" was the pen name of Willard Huntington Wright, a prominent art critic who initially sought to conceal his authorship of the novels. Van Dine was also a fictional character in the books, a sort of Dr. Watson figure who accompanied Vance and chronicled his exploits. Character

In the early novels, Van Dine claimed that "Philo Vance" was an alias, and that details of the sleuth's adventures had been altered to protect his true identity, even if "he has now gone to Italy to live".[1] This claim was conveniently forgotten as the series progressed. (A few years later, the same process occurred with another fictional detective, Ellery Queen, whose authors acknowledged being inspired by Van Dine.) As Van Dine described the character of Vance[2] in the first of the novels, The Benson Murder Case:

In the same book, Van Dine detailed Vance's physical features:

In the second adventure, The Canary Murder Case (set in 1927), Van Dine says that Vance was "not yet thirty-five... His face was slender and mobile; but there was a stern, sardonic expression to his features, which acted as a barrier between him and his fellows." Vance was highly skilled at many things: an "expert fencer", a golfer with a three handicap, a breeder and shower of thoroughbred dogs, a talented polo player, a master poker player, a winning handicapper of race horses, experience in archery ("a bit of potting at Oxford," as he referred to it), a patron of classical music, a connoisseur of fine food and drink, knowledgeable of chess, and of several foreign languages. He was also an expert on Chinese ceramics, psychology, the history of crime, ancient Egypt, Renaissance art, and a host of other recondite subjects. In The Kidnap Murder Case, in which Vance uses a gun, Van Dine describes Vance as a good marksman and a decorated World War I veteran. Van Dine says Vance's "one passion" is art. "He was something of an authority on Japanese and Chinese prints; he knew tapestries and ceramics: and once I heard him give an impromptu causerie to a few guests on Tanagra figurines..." (The Benson Murder Case) His interest in dogs is featured in The Kennel Murder Case (his polo playing is also mentioned in that case), his skill at poker in The Canary Murder Case, his ability to handicap race horses in The Garden Murder Case, his knowledge of chess and archery in The Bishop Murder Case, and of Egyptology in The Scarab Murder Case. His skills at golf and at fencing do not figure in any of the cases. Vance often wore a monocle, dressed impeccably (usually going out with chamois gloves), and his speech frequently tended to be quaint:

He was also a heavy smoker, lighting up and puffing on his Regies throughout the stories. According to some contemporary critics, these mannerisms of Vance were affectations, which made him look like a foppish dandy, a poseur. (See below for criticisms.) There is some indication that Van Dine wished the reader to question Vance's sexuality. In The Benson Murder Case, Vance is called a "sissy" by another character, and early in the book, as he is dressing, his friend Markham asks if he is planning to wear a green carnation, the symbol of homosexuality during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[3] PublicationVan Dine's first three mystery novels were unusual for mystery fiction because he planned them as a trilogy, but plotted and wrote them in short form, more or less at the same time. After they were accepted as a group by famed editor Maxwell Perkins, Van Dine expanded them into full-length novels. All 12 book titles are in the form "The X Murder Case," where "X" is always a six-letter word (except for The Gracie Allen Murder Case, which was originally just "Gracie"). Although Van Dine was one of the most educated and cosmopolitan detective writers of his time, in his essays he dismissed the idea of the mystery story as serious literature. He insisted that a detective novel should be mainly an intellectual puzzle that follows strict rules and does not wander too far afield from its central theme. He followed his own prescriptions, and some critics feel that formulaic approach made the Vance novels stilted and caused them to become dated in a relatively few years. All of the cases, except The Winter Murder Case, are mostly set in the Manhattan borough of New York City. On a few occasions, Vance and Van Dine (usually accompanied by Markham and Heath) briefly travel to the Bronx, Westchester County, and New Jersey in the course of their investigations. In The Greene Murder Case Vance tells, after his arrival back in New York, that he traveled by train to New Orleans to gather information relevant to the case. Vance's last case, The Winter Murder Case, is markedly different from the previous 11 cases in that the locale is away from New York (the Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts), and Vance and Van Dine are surrounded by an almost completely different cast of characters (only Markham makes a brief appearance at the very beginning). Wright had just finished writing this case when he died suddenly in New York on April 11, 1939. Novels

Cast of charactersMost of the adventures have at their beginning a "Characters of the Book," much as in Shakespeare's plays. Vance, Van Dine, John F.-X Markham, Ernest Heath, Dr. Emanuel Doremus, and Currie all appear in 11 of the 12 stories; the last, The Winter Murder Case, includes only Vance, Van Dine, and a brief appearance of Markham at the very beginning.

Other individuals who appear frequently include Francis Swacker, Markham's male secretary, and Guilfoyle, Hennessey, Snitkin, and Burke, all detectives under Heath in the Homicide Bureau. Criticisms of Vance and the novelsAt the height of Philo Vance's popularity, comic poet Ogden Nash wrote:

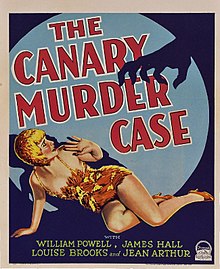

Famed hardboiled-detective author Raymond Chandler referred to Vance in his essay "The Simple Art of Murder" as "the most asinine character in detective fiction". In Chandler's novel The Lady in the Lake, Marlowe briefly uses Philo Vance as an ironical alias. A criticism of Vance's "phony English accent" also appears in Chandler's Farewell My Lovely. In Chandler's The Big Sleep, Marlowe says he's "not Sherlock Holmes or Philo Vance" and explains that his method owes more to judgement of character than finding clues the police have missed. Julian Symons in his history of detective fiction, Bloody Murder, says: "The decline in the last six Vance books is so steep that the critic who called the ninth of them one more stitch in his literary shroud was not overstating the case."[4] In A Catalogue of Crime, Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor criticize "… the phony footnotes, the phony English accent of Philo Vance, and the general apathy of the detective system in all these books …", in all the Vance novels. They review only seven of the 12 novels, panning all but the first and the last: The Benson Murder Case, which they call "The first and best …" and The Winter Murder Case, of which they write, "In fact, this short book is pleasant reading …"[5] In regard to Vance's supposedly phony accent, Van Dine addressed the issue early on. In The Greene Murder Case, one of the three original novels, he wrote that Vance's seemingly British manner of speaking was the result of his long education in Europe, not an affectation. He described Vance as indifferent to what people thought of him and not interested in impressing them. AdaptationsFilmsPoster for The Canary Murder Case (1929), featuring Louise Brooks Poster for The Benson Murder Case (1930), starring William Powell as Philo Vance Films about Vance were made from the late 1920s to the late 1940s, with some more faithful to the literary character than others. Fictional narrator S.S. Van Dine, who acts as a passive eyewitness to events in the novels, does not appear in the films. Among the several actors who played Philo Vance on the screen were William Powell, Warren William and Basil Rathbone, all of whom had great success playing other detectives in movies. The movie The Canary Murder Case is famous for a contract dispute that eventually helped sink the career of star Louise Brooks. William Powell did not enjoy playing Philo Vance, finding the role devoid of the complexity of a truly human character. After three Philo Vance films at Paramount, he flatly refused to play the role again. Later, at Warner Brothers, he was cajoled into making The Kennel Murder Case, due to studio pressure and the lack of more interesting scripts. A few years later Powell was offered The Casino Murder Case at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer into which a part was written for Myrna Loy as Vance's girlfriend, but Powell refused this film as well.[6] On Philo Vance as a role, Powell stated:

The Philo Vance novels were particularly well suited for films, where the more unpleasantly affected aspects of the main character could be toned down and the complex plots given more prominence. One of these films, The Kennel Murder Case, has been called a masterpiece by renowned film historian William K. Everson.

The plots of the final three films bear no relationship to any of the novels and very little relationship to the Philo Vance character of the novels. Philo Vance (William Powell) also appears in the "Murder Will Out" comic vignette of Paramount on Parade (1930), wherein Vance and Sgt. Heath (Eugene Pallette), along with fellow detective Sherlock Holmes (Clive Brook), go up against Fu Manchu (Warner Oland). Holmes and Fu Manchu were featured in their own respective series at Paramount at this time. Vance is mentioned in The Stolen Jools, an all-star film short produced by Paramount in 1931 to promote fundraising for the National Vaudeville Artists Tuberculosis Sanitarium, but does not appear. In the trailer for the first The Thin Man film in 1934, Powell plays both Vance and Nick Charles via split screen, as Charles tells Vance about the mystery he solves in the movie. At the time, The Thin Man's studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, had not produced a Philo Vance film since 1930, and the property was at that time contracted to Warner Bros. MGM regained the rights for 1935's The Casino Murder Case, but Powell did not appear in that film. Vance was also mentioned in The Lady Eve (1941). RadioThree radio drama series were created with Philo Vance as the title character.[9] The first series, broadcast by NBC in 1945, starred José Ferrer. A summer replacement series in 1946 starred John Emery as Vance. The best-known series (and the one of which most episodes survived) ran from 1948 to 1950 in Frederick Ziv syndication and starred Jackson Beck. "Thankfully, the radio series uses only the name, and makes Philo a pretty normal, though very intelligent and extremely courteous gumshoe. ... Joan Alexander is Ellen Deering, Vance's secretary and right-hand woman.”[10] George Petrie and Humphrey Davis also co-starred as DA Markham and Sgt. Heath respectively. TelevisionAn Italian-language TV miniseries from 1974 entitled Philo Vance featured Giorgio Albertazzi as Philo Vance. The series was composed of three episodes based on the first three Van Dine novels. The scripts were very faithful to the originals. References

External linksWikisource has original works on the topic: Philo Vance |

||||||||||||||||||||||