|

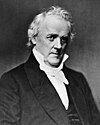

Philip Francis Thomas

Philip Francis Thomas (September 12, 1810 – October 2, 1890) was an American lawyer, mathematician[1] and politician. He served in the Maryland House of Delegates, was the 28th Governor of Maryland from 1848 to 1851, and was Comptroller of Maryland from 1851 to 1853. He was appointed as the 23rd United States Secretary of the Treasury in 1860 in the Buchanan administration. After unsuccessfully standing for the United States Senate in 1878, he returned to the Maryland House of Delegates, and later resumed the practice of law. Thomas was also elected twice to the United States House of Representatives, once in 1838 and again in 1874. He holds the all-time record for the longest break in between two terms of service in Congress, with 34 years separating his only two terms.[2][3] Governor of MarylandBorn in Easton, Maryland, he graduated from Dickinson College in Pennsylvania in 1830. He studied law and became a lawyer in Easton. Thomas was a delegate to the Maryland's constitutional convention in 1836 and a member of the Maryland House of Delegates in 1838, 1843, and 1845. He was elected as a Democrat to the 26th Congress in 1838 from Maryland's 2nd congressional district, but declined to run again in 1840. He went back to his law practice, but returned to politics eight years later when he was elected the 28th Governor of Maryland, a position he held through 1851. While Governor, in 1849 he commissioned Maryland's contribution to the Washington Monument,[4] a marble building stone upon which the colonial Sparrow Seal of Maryland[5] was engraved.[6] From 1851 to 1853, he was Comptroller of Maryland and then collector of the port of Baltimore from 1853 to 1860, and United States Commissioner of Patents for a fragment of that year (February through December).[7] Secretary of the TreasuryThomas was appointed United States Secretary of the Treasury in the Presidential Cabinet of President James Buchanan and served from December 12, 1860 until his resignation on January 14, 1861.[7]  When Howell Cobb, the 22nd Secretary of the Treasury resigned in 1860, Buchanan appointed Thomas the 23rd Secretary. Thomas reluctantly accepted the position. Immediately upon entering office, Thomas had to market a bond to pay the interest on the public debt. There was little faith in the stability of the country due to the threat of secession by the Southern United States, and war appeared inevitable. Northern bankers refused to invest in Thomas's loan, wary that the money would go to the South. Following Interior Secretary Jacob Thompson, Thomas resigned after only a month in response to his failure to obtain the loan.[7] However, other sources point to Thomas's "disagreement with (then President) Buchanan's emerging policy concerning South Carolina." [8] His letter of resignation reprinted in the New York Times states that his reason for doing so was [9] President Buchanan's reply accepting the resignation in that same New York Tines edition of January 17, 1861—six days after the event—stated that Thomas in his brief tenure as Secretary of the Treasury had discharged "duties in a manner highly satisfactory to myself." Later political careerTwo years later, he again became a member of the Maryland House of Delegates in 1863. He presented credentials as a senator-elect to the United States Senate for the term beginning March 4, 1867, but was not seated as a person "who had given aid and comfort" to the Confederate cause by way of giving money to his son "to aid him in joining the rebel army."[10] The charge against him was contested in The New York Times as "partisan intolerance," and in The Chicago Times as "lawless despotism."[10] However, Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan speaking to the Senate in mid-February 1868 had catalogued all of the ways in which Thomas had aided the insurrection: e.g., "only three days before he (Secretary Thomas) resigned his place as Secretary of the Treasury, the sub-treasury at Charleston, South Carolina was robbed deliberately by the rebels, plundered, taken into possession by the government there while Thomas here at Washington stands by quietly, offers no rebuke, makes no effort to defend the public treasure." [11] As his reason for resignation on January 11, 1861, Thomas cited "the purpose of the Cabinet and President to enforce the collection of the customs in the port of Charleston."[12] He was then elected as a Democrat to the 44th Congress from the 1st Congressional district of Maryland, serving from 1875 to 1877, and declined to be a candidate for renomination in 1876.[13] He was an unsuccessful candidate for election to the United States Senate in 1878. He returned to the Maryland House of Delegates twice, in 1878 and 1883, and then resumed the practice of law in Easton.[13] Death and burialHe died in Baltimore in 1890 and is buried in Spring Hill Cemetery in Easton.[13] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||