|

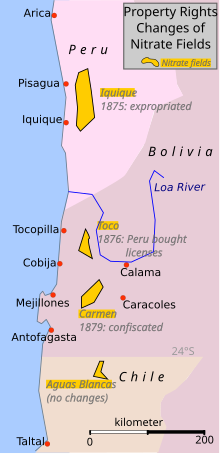

Peruvian nitrate monopoly The Peruvian nitrate monopoly[A] was a state-owned enterprise over the mining and sale of saltpeter (sodium nitrate)[nota 1] created by the government of Peru in 1875 and operated by the Peruvian Nitrate Company.[2] Peru intended for the monopoly to capitalize on the world market's high demand for nitrates, thereby increasing the country's fiscal revenues and supplementing the financial role that guano sales had provided for the nation during the Guano Era (1840s-1860s). During the 19th century Peru established a virtual international monopoly in the trade of guano, another fertilizer, and since the 1840s income from this source had financed the Peruvian Guano Era. By the 1860s these revenues were in decline, as deteriorating quality led to a reduction of exports. Alongside this trend, nitrate exports from the Peruvian province of Tarapacá grew, and became an important competitor to guano in the international market.[3]: 108 In January 1873 the government of Manuel Pardo imposed an estanco, a state control on production and sales of nitrate, but this proved impractical, and the law was shelved in March 1873 before it was ever applied. In 1875, as the economic situation deteriorated and Peru's overseas debts increased, the government expropriated the saltpeter industry and imposed a full state monopoly on production and exports.[3] However, there were nitrate deposits in Bolivia and Chile, and although the latter were not economically viable, exports from Bolivia by the Chilean Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA) made Peruvian price controls impossible. Following the Peruvian state's failure to raise new loan capital from Europe to finance its nationalization program, the government proceeded to acquire Bolivian licenses to exploit newly discovered nitrate fields, and encouraged the Bolivian government to withdraw from the Boundary Treaty of 1874 between Chile and Bolivia. This treaty had fixed for 25 years the tax rate on the Chilean saltpeter company, in return for Chile's relinquishing of its sovereignty claims over the disputed region of Antofagasta. In 1878 the Bolivian Government imposed a 0.35 Pounds Sterling per tonne (10 cents Bolivian Bolivianos per 100 kg)[nota 2] tax over the CSFA's export of saltpeter, contrary to Article IV of the Boundary Treaty. Although it is uncertain whether Peru exerted direct pressure on Bolivia to impose this tax, its consequence was the confiscation and auctioning off of the CSFA, the major competitor to Peruvian saltpeter. Historians agree that control over the nitrate fields in the Atacama were a central cause for the start of the War of the Pacific.[4][5] Some Chilean historians consider that the Peruvian plan to control the price and production of the Bolivian nitrate fields was what ultimately caused the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).[6] According to the Chilean government, Peru's actions were the primary cause of the 1879 war.[7] However, most historians consider that the war was actually precipitated by the Chilean government's expansionist foreign policy and its ambitions over the Atacama's mineral wealth in Bolivian and Peruvian territory.[8][9][10] Prosperity and bankruptcy

Peru was rich in guano, a highly effective fertilizer because of its exceptionally high content of nitrates, phosphates and potassium, which had since the 1840s provided the government with dramatically increasing revenues. To obtain the best possible price for the guano, the Peruvian state established a system of consignment to private companies, to sell the product in Europe and the United States. The consignees were important elements in the government's finances, because they delivered the cash and credits for the government's spending. From the beginning of the guano exports until 1869, the consignees were Peruvian traders. In 1865 a coup d'etat brought a new Peruvian leader, Mariano Ignacio Prado. During his first administration (1865-1868) the finance minister, Manuel Pardo (later President of Peru 1872-1876), needed fresh revenues to replace the declining guano income, and imposed new taxes on saltpeter, wool, sugar, cotton, etc., as well as an inheritance and property transfer tax. Opposition to the new taxes (see cartoons), combined with the weak Peruvian economy and its bureaucratic inefficiency, the new taxes yielded much less than expected. Prado resigned in 1868 and most of his new taxes were subsequently abolished.[11]: 65, 77–79 In July 1869 the new government contracted with a French businessman, Auguste Dreyfus to sell two million tons of guano over a six-year period. This contract gave Peru access to the international financial markets and enabled President José Balta (1868-1872) to raise loans of £36 million in Europe. However, the proceeds were spent on unprofitable public undertakings and prestige projects such as the sumptuous Peruvian Exposition of 1872. As a result, Peru accumulated a large internal debt and a serious budget deficit. The quality and quantity of guano exports also declined over these years, and from the 1860s saltpeter exports competed with guano in the international markets. Unlike the production and marketing of guano, which was in the hands of the government, the saltpeter industry was privately owned and operated. In June 1876, the Peruvian Guano Company[nota 3], owned by the Peruvian Raphael Holding, became the consignee for Europe through the Raphael Contract.[11]: 104 There are several benchmarks or dates for the crisis. The second administration of President Prado (1876-1879) had six Finance Ministers, none of whom lasted a year. Contreras Carranza cites 1873 as marking the crisis. The Dreyfus organisation suspended the payment of guano export revenues to the Peruvian State, because all the money was spent in debt service.[11]: 83, 101 Guano exports fell from 575,000 tons in 1869 to less than 350,000 tons in 1873, and the Chincha Islands and other guano islands were depleted or almost depleted. Also, the quality (nitrogen content) of the guano fell.[3]: 112 By contrast, saltpeter was increasing its share in the export market: while some 1.7 million tonnes had been shipped from Tarapacá between 1860 and 1870, in the following decade the figure rose to over 4.4 million tonnes.[12] The falling income from guano was outweighed by the increasing volume of saltpeter sales and also by the increasing sugar exports; Contreras states that the real cause of the crisis was the debt contracted in 1870-1872.[11]: 102–103 He specifies the failure of Balta's railroad plans as the origin of the disaster: from 1868 to 1875, 130 million soles were invested in eleven railroad lines, but only four were completed between places of commercial importance, and only one of these according to plan. The annual revenue of 600,000 soles represented a yield of only one-tenth of the usual 5% or 6% per annum interest on South American investments at the time.[11]: 121–125 Peruvian opposition to new taxes Who would pay the new taxes: a jobless man, a demobilized soldier, a priest without a church, a monk without a monastery, a widow without a pension Pardo keeps the guano revenue, and spreads a new illness: "impuestitis" (a pun based on impuesto ("tax") and the suffix -itis, meaning inflammation).[13] Faced with a dramatic decline in guano revenues, the government desperately needed to find additional sources of revenue. The Peruvian magazine "El Cascabel" (1872) scoffed at the proposed measures. ProposalsBy 1872 the declining income from guano was insufficient to service state debts. On 28 September Manuel Pardo, now Peru's president, announced in his inaugural address that the state was bankrupt and that he had to apply long-term solutions: administrative decentralization, an increase in customs duties, and an export duty on nitrate. He began his administration in the conditions he had warned about in 1866 when he was finance minister: rising debts and falling guano revenues.[11]: 84 The discussion of Pardo's proposals produced two options for increasing revenue. The nitrate producers, who wanted to keep control over production volume and costs, favored a new tax on exports depending on the international price. A second idea, promoted by the guano traders who were eager to participate in the nitrate business, was to create a state monopoly on nitrate sales. An ad hoc senate committee advocated an export tax or, alternatively, a nationalization of the nitrate fields,[11]: 87–88 which would stop competition between the two fertilizers and bring the nitrate profit directly into the government treasury. The guano traders, who had been displaced from the guano commerce by the Dreyfus Contract, were interested in a state control on the nitrate industry – control of production and output quotas, or even the expropriation of the salitreras, in the hope of earning a greater part of the new lucrative business. They therefore supported the Civilista Party, and its state control law (Ley del Estanco). The nitrate producers were represented[11]: 106 by Nicolas de Pierola, who voiced a prevailing public mood against the guano traders and the elite of Lima. Carlos Contreras writes:

Henry Meiggs also secretly supported Pierola's uprising against the government of Prado.[1]: 116 (which provoked the Battle of Pacocha on 29 May 1877 between the Peruvian ship Huáscar and the British ship HMS Shah.) Estanco del Salitre

As well as the new[nota 4] tax proposed by the senate committee, the government prepared to create a state monopoly of nitrate sales; the "Ley del Estanco" (Monopoly Law) was issued on 18 January 1873,[14] to become effective after two months. The Peruvian state would pay 24 soles per tonne[nota 5] to the producers, and if the nitrate sold for over 31 soles per tonne the state and the producers would share the profits. The law also set production quotas based on capacity and existing output. Unexploited saltpeter fields were transferred to the state, further private investments in the nitrate industry was forbidden. Four Peruvian banks, Nacional, Providencial, Perú and Lima, would undertake the administration of the Monopoly Law.[3]: 113 Producers could export their product directly, but they had to pay to the state the excess of any price over 31 soles per tonne. As stated by the newspaper El Comercio (Peru) on 30 September 1872, the new law would regulate the nitrate supply, increase the price, eliminate the competition between guano and salitre, and displace Chilean investors from Tarapaca.[16] On the other hand, it threatened the independence of the producers, who had created their own enclave in a sparsely populated and infertile region physically isolated from the rest of Peru. The industry was largely organized by foreigners and net income went overseas. Materials, capital and equipment were brought from Valparaiso or Europe. The companies resented the allocation of quotas, and refused to co-operate. In February, in a "fear of gate closing", as firms raised output to increase their quotas, the saltpeter price fell to 18.70 soles per tonne, less than the government had promised to pay to the producers. In March 1873 the government postponed the law, and in the autumn shelved the entire plan.[17] Greenhill & Miller cite as reasons for the project's failure the political crisis in Lima, high administrative costs, a lack of trained officials, and Valparaiso's strength as a sales center. Two measures survived the disaster: the export duties of 1.50 soles per tonne, and the "Compañía Administradora del Estanco del Salitre" to collect export duties.[3]: 114–115 Expropriation of the salitrerasThe competition between guano and saltpeter sharpened and the state finances worsened, despite the fresh money from the saltpeter export tax.[11]: 93 On 28 May 1875 a Nationalization Law was issued; this stipulated that all the nitrate industry in Peru was to be expropriated and their owners compensated according to a property appraisal. For this purpose a loan of £7 million had to be raised in Europe. The new state "Compañía Salitrera del Perú" (from 1878 "Compañía Nacional del Salitre" under Banco de la Providencia) would supervise production, set output quotas and a ban on further investment was issued. Technically this was not a compulsory purchase; rather the law authorized the state to buy nitrate property. All owners had to continue the work of their oficinas for the government. Producers who opposed state interference or were confident in their abilities could continue to work in their properties, albeit under a higher export duty. But Peru's (and South America's in general) lack of creditworthiness and the state of European money markets prevented Peru from raising the required £7 million loan in Europe; rather than paying in cash, the Peruvian state had to offer the mine owners two-year certificates bearing 8% interest and a 4% sinking fund in exchange for the properties, although some small salitreras were paid in cash.[18][3]: 117 Greenhill & Miller agree that "The severity of the financial crisis and the approaching termination of Pardo's presidency unduly hastened its completion."[3]: 118–119 Dishonest officials, lack of managerial expertise, unclear ownership rights, spurious claims of output and ownership.[19] Moreover, equal bonds were issued for different kind of properties (real estate, machines, spare parts, consumables), some bonds were made out to bearer or nominal payee and some bonds weren't assigned to a specific property. This made possible speculation.[1]: 109 [20] Also the long delay (12 months) between proposing and implementing the expropriation encouraged abnormally high output and consequently a low price of saltpeter, beside the Great Depression of British Agriculture. Anthony Gibbs and Sons's "Compañía de Salitres de Tarapacá" got a "good, even inflated price" for its nitrate properties and Crozier remarks that they were ready to work for the government only for the profit derived from the iodine production, a fact that was unknown to the Peruvian government.[1]: 109–110 Quest for control of Bolivian nitrateThe Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA) was a Chilean company, based in Valparaiso; a 29% minority share was held by the British Anthony Gibbs and Sons. From the 1860s the company had exploited the nitrate fields in Antofagasta, with a tax exemption license of the Bolivian government.[1]: 99–100 Beyond that, article IV of the Boundary Treaty between Chile and Bolivia of 1874 explicitly ruled out new or higher taxes upon Chilean companies or persons working in Antofagasta. The CSFA was the only competitor of Peruvian saltpeter in the international markets, and the urgent necessity to maintain the prices of saltpeter and guano brought the Peruvian government to intervene actively in the Bolivian saltpeter policy. On February 6, 1873, a few days after the signing of the Ley del Estanco, the Peruvian senate approved the secret treaty of alliance between Peru and Bolivia; the parliamentary proceedings have disappeared since then.[21] Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre asserts that the two projects were unrelated to each other, but Hugo Pereira Plascencia has contributed several items of evidences to the contrary: in 1873 the Italian author Pietro Perolari–Malmignati cited the Peruvian interest in defending its saltpeter monopoly against the Chilean production in Bolivia as the main cause of the secret treaty, and also said that the Peruvian Foreign Minister, José de la Riva-Agüero informed the Chilean Minister in Lima, Joaquín Godoy, about negotiations with Bolivia to expand the estanco in Bolivia.[22] In 1876 the Peruvian government bought the saltpeter licenses for "El Toco" fields in Bolivia through an intermediary, Henry Meiggs, the builder of the Peruvian railroads, but also with the involvement of Anthony Gibbs and Sons, the company that would owe Bolivia for the licenses. The picturesque agreement, as Crozier called it, about property would have long standing consequences; it was called "Caso Squire" in the Chilean courts after the war.[1]: 116 In 1876 President Pardo urged Gibbs to ensure the success of the monopoly by limiting the production of the CSFA, and in 1878, Anthony Gibbs and Sons warned the management board of the CSFA that they would get trouble with a "neighbouring Government" [sic] if they insisted on swamping the market with their nitrate.[23]: 69 Bolivian historian Querejazu cited George Hicks, manager of the Chilean CSFA, who knew that the highest bidder for the confiscated property of the CSFA on 14 February 1879 would be the Peruvian consul in Antofagasta.[24] The Anthony Gibbs and Sons, represented in South America by (Williams or) Guillermo Gibbs & Cia. of Valparaiso, had much more important investments in Peru than in Chile. In Peru, the House of Gibbs owned of 58% of the Compañía de Salitres de Tarapacá[1]: 82 ("Tarapaca Nitrate Company") and had been guano consignee of the government in Europe.[3]: 120–121 The Bolivian ten cents taxOn 14 February 1878, the Bolivian senate enacted a new tax of 7 shillings[nota 2] per tonne on the export of nitrate. The CSFA refused to pay the new tax because of article 4 of the Border Treaty and the License. In February 1879, the Bolivian government retired the license of exploitation and confiscated the property of the company. On 14 February 1879, Chilean troops occupied the port of Antofagasta, which was populated by a majority of Chileans. Bolivia declared war on Chile on 1 March 1879. Peru, allied with Bolivia under the secret treaty, pretended to mediate, but as the Chilean government asked Peru to declare its neutrality, Peru tried to delay negotiations. Chile declared war on Peru and Bolivia on 5 April. Ronald Bruce St John put it in the following words:[26]

War of the Pacific In November 1879, during the Tarapacá Campaign, the Chilean Army seized the Peruvian salitreras and most of the guano deposits, whose export ports were already under blockade by the Chilean Navy. On 12 September 1879, five months after beginning of the war, the Chilean government had imposed a tax of 4 Chilean pesos[nota 6] per tonne upon Antofagasta's export of saltpeter to finance the war effort, despite protest by the Chilean CSFA. After the occupation of Tarapaca, the Chilean government had to decide what to do with the nitrate industry. They had two alternatives: to follow Peru's way, i.e. to pay the Peruvian debt certificates (£4 million[27]: 28 ) and create a state company to manage the production and marketing of nitrate; or to return the property to the holder of nitrate certificates and let them restart the business. The Chilean government decided on the latter course: on 11 June 1881 (provisionally) and on 28 March 1882 (definitively) they allowed the bondholders to retake their properties and continue the exploitation.[20] The decision to privatization has been much criticized and Chile lamented for having been duped into losing her economic future to the hands of "predatory" capitalists. But William Edmundson states:

He cites the catastrophic Peruvian attempt, the uncertainty over the property rights, the immense fiscal and bureaucratic burden, and that for the public opinion in Chile "government ownership of the means of production was regarded as beyond the ideological pale".[27]: 27–28 The Treaty of Ancon in 1883 formally ceded Tarapacá to Chile and finished the Peruvian control over the nitrate fields. But the court proceedings in Peru, Chile and Europe about property rights and debts continued until 1920. AftermathHistorians agree that the monopoly did not meet the expectations set out in the law of 1875, and that the same or higher revenues could have been obtained with a simple export tax.[18][28][29]: 2235 According to Carlos Contreras Carranza, there are two views on the law's significance for Peru. While some authors consider that the war interrupted a fiscal reform which was not irrevocably doomed to fail, other historians see it as yet another improvised policy, which the easy guano revenues had generated.[11]: 129 In the former view, the nationalization was the birth of a new bourgeoisie, national and progressive; in the latter view it was an abortion of a new bourgeoisie of Tarapacá, expropriated and displaced from the business in favor of Lima's old elite, accustomed to enriching themselves from state economy.[11]: 96 On the eve of the war, Guillermo Billinghurst, then a member of the Peruvian senate and later president of Peru, advocated the restitution of the salitreras to the former owners, but the outbreak of war made a discussion impossible.[29]: 2236 In 1890 the Peruvian government approved a settlement, known as the Grace Contract, which resulted in the holders of Peruvian sovereign debt taking control of the country's railroads. The government did not issue new sovereign debt until 1906.[30] While the origins of the War of the Pacific are closely related to saltpeter, Peruvian historiography has been reluctant to review the issue.[31] Regarding this attitude, the Bolivian historian said that "it is a egregious lie that Peru went to war only to help Bolivia".[32] After the war, Chile possessed all guano and saltpeter fields of the Pacific Coast of South America, but never built a state monopoly. Nonetheless, its control gave the country a virtual monopoly of nitrates, and the income acquired from its taxation allowed the country to fund its development. During the 20th century, Chile would further exploit the Atacama's mineral wealth by nationalizing the copper industry. See also

Notes and referencesNotes

References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||