|

Perspectivity

In geometry and in its applications to drawing, a perspectivity is the formation of an image in a picture plane of a scene viewed from a fixed point. GraphicsThe science of graphical perspective uses perspectivities to make realistic images in proper proportion. According to Kirsti Andersen, the first author to describe perspectivity was Leon Alberti in his De Pictura (1435).[1] In English, Brook Taylor presented his Linear Perspective in 1715, where he explained "Perspective is the Art of drawing on a Plane the Appearances of any Figures, by the Rules of Geometry".[2] In a second book, New Principles of Linear Perspective (1719), Taylor wrote

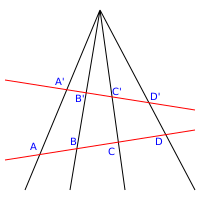

Projective geometry In projective geometry the points of a line are called a projective range, and the set of lines in a plane on a point is called a pencil. Given two lines and in a projective plane and a point P of that plane on neither line, the bijective mapping between the points of the range of and the range of determined by the lines of the pencil on P is called a perspectivity (or more precisely, a central perspectivity with center P).[4] A special symbol has been used to show that points X and Y are related by a perspectivity; In this notation, to show that the center of perspectivity is P, write The existence of a perspectivity means that corresponding points are in perspective. The dual concept, axial perspectivity, is the correspondence between the lines of two pencils determined by a projective range. ProjectivityThe composition of two perspectivities is, in general, not a perspectivity. A perspectivity or a composition of two or more perspectivities is called a projectivity (projective transformation, projective collineation and homography are synonyms). There are several results concerning projectivities and perspectivities which hold in any pappian projective plane:[5] Theorem: Any projectivity between two distinct projective ranges can be written as the composition of no more than two perspectivities. Theorem: Any projectivity from a projective range to itself can be written as the composition of three perspectivities. Theorem: A projectivity between two distinct projective ranges which fixes a point is a perspectivity. Higher-dimensional perspectivitiesThe bijective correspondence between points on two lines in a plane determined by a point of that plane not on either line has higher-dimensional analogues which will also be called perspectivities. Let Sm and Tm be two distinct m-dimensional projective spaces contained in an n-dimensional projective space Rn. Let Pn−m−1 be an (n − m − 1)-dimensional subspace of Rn with no points in common with either Sm or Tm. For each point X of Sm, the space L spanned by X and Pn-m-1 meets Tm in a point Y = fP(X). This correspondence fP is also called a perspectivity.[6] The central perspectivity described above is the case with n = 2 and m = 1. Perspective collineationsLet S2 and T2 be two distinct projective planes in a projective 3-space R3. With O and O* being points of R3 in neither plane, use the construction of the last section to project S2 onto T2 by the perspectivity with center O followed by the projection of T2 back onto S2 with the perspectivity with center O*. This composition is a bijective map of the points of S2 onto itself which preserves collinear points and is called a perspective collineation (central collineation in more modern terminology).[7] Let φ be a perspective collineation of S2. Each point of the line of intersection of S2 and T2 will be fixed by φ and this line is called the axis of φ. Let point P be the intersection of line OO* with the plane S2. P is also fixed by φ and every line of S2 that passes through P is stabilized by φ (fixed, but not necessarily pointwise fixed). P is called the center of φ. The restriction of φ to any line of S2 not passing through P is the central perspectivity in S2 with center P between that line and the line which is its image under φ. See alsoNotes

References

External links

|