|

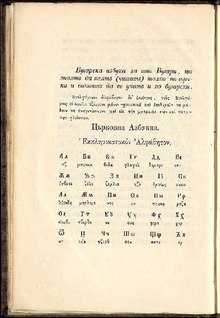

Parteniy Zografski   Parteniy Zografski or Parteniy Nishavski[1][2][3] (Bulgarian: Партений Зографски/Нишавски; Macedonian: Партенија Зографски; born Pavel Hadzhivasilkov Trizlovski; 1818 – February 7, 1876) was a 19th-century Bulgarian cleric, philologist, and folklorist from Galičnik in today's North Macedonia, one of the early figures of the Bulgarian National Revival.[4][5] In his works he referred to his language as Bulgarian and demonstrated a Bulgarian spirit, though besides contributing to the development of the Bulgarian language,[6][7][8] in North Macedonia he is also thought to have contributed to the codification of present-day Macedonian.[9] BiographyReligious activityZografski was born as Pavel Hadzhivasilkov Trizlovski (Павел Хадживасилков Тризловски) in Galičnik,[10][11] Ottoman Empire, in present-day North Macedonia. Born into the family of a rich pastoralist, young Pavel had the opportunity to attend various primary and secondary schools. He started his education in the Saint Jovan Bigorski Monastery near his native village, then he moved to Ohrid in 1836, where he was taught by Dimitar Miladinov. He also studied in Prizren and at the Greek schools in Thessaloniki, Istanbul and a seminary in Athens.[12] Trizlovski became a monk at the Zograf Monastery on Mount Athos, where he acquired his clerical name. Zografski continued his education at the seminary in Odessa, Russian Empire; he then joined the Căpriana monastery in Moldavia. He graduated from the Kiev seminary in 1846 and from the Moscow seminary in 1850. Aged 32 he was already a spiritual advisor at the imperial court in St. Petersburg. After a short stay in Paris (1850), he returned to serve as a priest at the Russian church in Istanbul until he established a clerical school at the Zograf Monastery in 1851 and taught there until 1852. From 1852 to 1855, he was a teacher of Church Slavonic at the Halki seminary; from 1855 to 1858, he held the same position at the Bulgarian school in Istanbul, also serving at the Bulgarian and Russian churches in the imperial capital, and he became an active supporter of the opposition against Greek dominance in the religious and educational spheres. He spent the winter of 1859 in Sofia where he ordained dozens of Bulgarian priests.[13] On 29 October 1859, at the request of the Municipality of Kukush (Kilkis), the Patriarchate appointed Zografski Metropolitan of Dojran in order to counter the rise of the Eastern Catholic Macedonian Apostolic Vicariate of the Bulgarians. Parteniy Zografski co-operated with the locals to establish Bulgarian schools and increase the use of Church Slavonic in liturgy. In 1861, the Greek Orthodox Church Metropolitan of Thessaloniki and a clerical court prosecuted him, but he was acquitted in 1863. In 1867, he was appointed Metropolitan of Nishava in Pirot. At this position, he supported the Bulgarian education in these regions and countered the Serbian influence.[14] From 1868 on, Parteniy Zografski broke away from the Patriarchate and joined the independent Bulgarian clergy. Between 1868 and 1869, Bishop Partheniy became active in the region of Plovdiv, where he began to ordain priests for the Bulgarian Church, which had already separated from the Patriarchate, but had not yet been confirmed.[15] After the official establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870 he remained a Bulgarian Metropolitan of Pirot until October 1874, when he resigned. Zografski died in Istanbul on 7 February 1876 and was buried in the Bulgarian St. Stephen Church. Linguistic activity Besides his religious activity, Zografski was also an active man of letters. He co-operated with the Bulgarian Books magazine and the first Bulgarian newspapers: Savetnik, Tsarigradski Vestnik and Petko Slaveykov's Makedoniya. In 1857, he published a Concise Holy History of the Old and New Testament Church. The following year he published Elementary Education for Children in Macedonian vernacular. Per Zografski the Bulgarian language was divided into two major dialects, Upper Bulgarian and Lower Bulgarian; the former was spoken in Bulgaria (i.e. modern North Bulgaria), in Thrace, and in some parts of Macedonia, while the latter in most of Macedonia.[16] In 1857 he espoused this linguistic view in an article published in Tsarigradski vestnik and called "The following article is very important and we encourage readers to read it carefully":[17]

In the next year, Zografski argued that the Macedonian dialect should represent the basis for the common modern "Macedono-Bulgarian" literary standard called simply Bulgarian in another article published in Balgarski knizhitsi called "Thoughts about the Bulgarian language":[19][20]

The division of the dialects of the Eastern South Slavic into western and eastern subgroups made by Zografski is still relevant today, while the so-called yat border is the most important dividing isogloss there.[22] It divides also the region of Macedonia running along the Velingrad–Petrich–Thessaloniki line.[23] In 1870 Marin Drinov, who played a decisive role in the standardization of the Bulgarian language, rejected the proposal of Parteniy Zografski and Kuzman Shapkarev for a mixed eastern and western Bulgarian/Macedonian foundation of the standard Bulgarian language, stating in his article in the newspaper Makedoniya: "Such an artificial assembly of written language is something impossible, unattainable and never heard of."[24][25][26] However, in the year that Zografski died (1876), Drinov visited his birthplace and studied the local Galičnik dialect, which he regarded as part of the Bulgarian diasystem, publishing afterwards the folk songs collected there.[27] The fundamental issue then was in which part of the Bulgarian lands the Bulgarian tongue was preserved in a most true manner and every dialectal community insisted on that. In fact Bulgarian was standardized later on the basis of the eastеrly from the yat border located Central Balkan dialect, because of the then belief that in the Tarnovo region, around the last medieval capital of Bulgaria, the language was preserved allegedly in its purest form.[28] Ethnic activismIn 1852, a small group of Bulgarian students established a Bulgarian cultural society named Balgarska matitsa (Bulgarian Motherland) in St. Petersburg and among those who joined was Parteniy Zografski from Istanbul. The Matitsa was replaced later by the Obshtestvo bolgarskoy pismennosti (Society of Bulgarian literature), founded in Istanbul in 1856, where he joined too. The Obshtestvo soon had its own magazine: Balgarski knizhitsi (Bulgarian Booklets) where Zografski published a lot of articles.[29] Zografski as a Bulgarian Exarchate bishop was active also in the struggles for the establishment of a distinct Bulgarian Orthodox Church, when the modern Bulgarian nation had been established.[30] In 1859, as the director of the Bulgarian school in Istanbul, he composed the text carved on a copper plate embedded in the foundations of the new Bulgarian church there. He regarded his vernacular as a version of Bulgarian language and called the Macedonian dialects Lower Bulgarian, while designating the region of Macedonia Old Bulgaria. On that basis Bulgarian scholars, maintain that he was a Bulgarian national revival activist and his ideas about a common literary Bulgarian standard based on western Macedonian dialects were about a common language for all the Bulgarians.[31] Macedonian historiography on Zogravski's ethnicitySince the times of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, historians in present-day North Macedonia have insisted Zografski's literary works published in western Macedonian vernacular make him a leading representative of the "Macedonian National Rebirth". He is interpreted by them and literary scholars there as a supporter of an idea for a two-way Bulgaro-Macedonian compromise, not unlike the one achieved by Serbs and Croats with the 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement.[31][32] External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parthenius of Zograf. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikiquote has quotations related to Parteniy Zografski. References

|