|

Paris–Saint-Germain-en-Laye railway

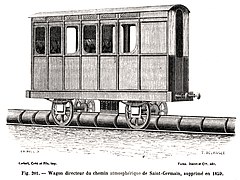

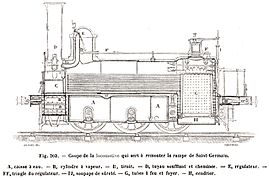

The Paris–Saint-Lazare–Saint-Germain-en-Laye line is a 20.4 km (12.7 mi) long double-track suburban railway line in France, connecting Paris-Saint-Lazare station (8th arrondissement of Paris) to Saint-Germain-en-Laye station, in the Yvelines department. It is now designated as line no. 975 000 of the national rail network. Inaugurated in 1837 between Paris and Le Pecq, it was the first railway line built from Paris, but also the first in France designed solely for passenger transport and operated using steam locomotives, five years after the opening between 1830 and 1832 of the Saint-Étienne–Lyon railway, built by the brothers Paul and Marc Seguin. Transport on this last line was intended for goods and passengers, and traction was entrusted to Seguin locomotives with tubular boilers. On the Saint-Étienne–Andrézieux railway, the first line built on the continent and opened in 1827, horse-drawn traction was initially used. The Paris to Le Pecq line was modernised during the 1920s with third rail electrification and the introduction of Z 1300 ("Standard") trains. Its western half has been incorporated into RER line A since 1972 and is operated by the Régie autonome des transports parisiens (RATP). The rest of the line is operated by the Société nationale des chemins de fer français (SNCF) and forms a branch of Transilien Line L. HistoryIn 1825, the Stockton and Darlington Railway was opened in Great Britain. It was the first in the world to provide passenger transport with steam locomotives. In 1827, the Saint-Étienne–Andrézieux railway was opened in France. The first railway in continental Europe, it was designed for goods traffic with horse traction before being used by steam locomotives. This line was extended to Roanne, 80 km (50 mi) to the north, in 1833. To cross the foothills of the mountains near Neulise, between Balbigny and l'Hôpital-sur-Rhins, it used four inclined planes inspired by what was done in England for river boats. The same year, the Budweis–Linz–Gmunden Horse-Drawn Railway was opened in Austria,[1] From 1830 to 1832, the railway line from Saint-Étienne to Lyon was opened, which was the first in France to experiment with traction by steam locomotives and, from 1831, with passenger transport. Elsewhere in Europe, in 1835, the lines from Brussels to Malines in Belgium and from Nuremberg to Fürth in Bavaria were opened. It was in this context that a railway line linking Paris to Saint-Germain-en-Laye was envisaged by the Pereire brothers, who requested a concession for its construction in 1832.[1] The first railway line in the Île-de-France The success of the railway line from Saint-Étienne to Lyon[2] quickly made the national government aware of the importance of developing this new mode of transport. Indeed, the speed and savings achieved as a result of building the railway brought immediate economic development to the Saint-Étienne region at the beginning of the 1830s. It therefore seemed essential to build a line from the capital, to make this new means of transport known to the public, and thus arouse the interest of politicians and financiers.[1]  The Pereire brothers[3] were the first to propose the construction of a line from Paris, and sought the concession in 1832. They obtained it by law on 9 September 1835[4] and on 2 November following, created the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Saint-Germain (Paris to Saint-Germain Railway Company) to manage its creation and operation. This company was authorised by a royal decree on 4 November 1835.[5] The line was to connect the capital to Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a popular Sunday stroll spot for Parisians, whose proximity to Paris limited the investments required. In addition, its position west of Paris made it possible to make this section to be built a first link on a main line to Rouen, considered a priority to be built.[6] The studies were carried out by civil engineers Eugène Flachat and his brother Stéphane Mony (Flachat) and mining engineers Émile Clapeyron and Gabriel Lamé.[7] Then, Stephane Mony (Flachat), Clapeyron and Lamé became the engineers of the company[8] and Eugène Flachat its director.[7] The route to Le Pecq, 19 km (12 mi) long, is located on the plain and, apart from two river crossings, presented few construction difficulties. With no significant ramp or tight curve, it required the construction of few engineering structures: two bridges over the Seine, the Asnières railway bridge and the Chatou railway bridge, as well as the 321 m (1,053 ft) long Batignolles tunnel to cross the Monceau hill (demolished in 1922-1926). At first, simple wooden bridges were made do. The work was quickly carried out under the direction of Eugène Flachat.[7] This construction of the tunnel was to provoke mockery. François Arago declared: "I affirm without hesitation that in this sudden passage, people subject to sweating will be inconvenienced, that they will gain chest infections and pleurisy".[9] Another author warns travellers against the "fleeting succession of images that are likely to set the retina on fire".[10] Beyond Clichy, the route, in a sector that was still relatively undeveloped, posed fewer expropriation problems than in the immediate and more urbanised surroundings of Paris; it crossed fields and forests for most of this final section. At the time, the terminus of the line was at the port of Le Pecq,[3] on the right bank of the Seine. The locomotives were indeed incapable of tackling the ramp required to climb the Saint-Germain hillside, which towers several dozen metres above the river. The line had only a single track, without even the smallest intermediate crossing loop for trains to pass,[6] whereas the specifications of 1835 required at least two parallel tracks (see the specifications following the Law on the Concession of the Paris to Saint-Germain Railway, no. 348, of 9 July 1835, signed by Louis-Philippe, King of the French, Adolphe Thiers, Minister of the Interior and Jean-Charles Persil, Keeper of the Seals of France, Minister of Justice). The work was progressing quickly as noted by Le Moniteur universel of 3 August 1836:[11] "The work on the railway from Paris to Saint-Germain is in full swing along the entire line, although the harvest work has made workers quite rare. If one could judge, by what is happening today, the influence that this communication will have on the localities it crosses, the results would be extremely favourable. It is above all a source of prosperity for the commune of Batignolles-Monceaux; all the inns on the Barrière Monceaux are crowded, at meal times, with the five hundred workers who work in the Paris underground and in the earthworks of the Batignolles plain. The movement of curious onlookers, who travel to the plain to see the manoeuvres of the wagons, on the temporary railways already established over a great length, maintains an extraordinary activity in the commune." Although the construction of the line posed few problems, the positioning of the terminus in Paris was the subject of heated debate. The Pereire brothers wanted an embarcadère (pier)–the term or a station at that time–on Place de la Madeleine (cf. Gare de la Madeleine), with a viaduct on Rue Tronchet towards Batignolles. But following protests from local residents, the pier was finally placed below Place de l'Europe. The facilities were basic, and access was via ramps and stairs.[6] As the Saint-Germain hill was too steep to be climbed by a steam train, the line terminated at Le Pecq, then a stagecoach transported passengers to Saint-Germain. The inauguration of the line takes place on 24 August 1837 in the presence of the royal family and in particular Queen Maria Amalia, but in the absence of King Louis-Philippe. The latter preferred to travel by horse-drawn carriage and the government had dissuaded him from exposing himself to the risks of such a journey. The inaugural journey took 25 minutes. The inauguration met with considerable response and was reported at length by the press. The day after, on 26 August, the line was opened to the public, and Parisians rushed to discover the new railway at the "pier" on the Place de l'Europe: 18,000 passengers were transported on the first day of operation.[6] In the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, Jules Janin raved: "Yesterday, going to Saint-Germain was a journey; today it is just a matter of leaving one's house." L'Écho français appreciated the technical feat ("We were struck to the highest degree by the magic of this communication, so rapid and so to speak instantaneous"), while putting it into perspective: "but the eccentricity of the points of departure and arrival make it an object of curiosity and exhibition rather than of utility and exploitation." Its lasting success would belie this reservation.[12] Parisians appreciated the speed of transport, which took less than half an hour. This was considerable progress compared to the Coucous (cuckoos), horse-drawn carriages, which took 5 to 6 hours to travel from the Tuileries to Saint-Germain.[13] At the start of operations, ten round trips per day were operated, using a single train. Departures were scheduled every 90 minutes, from 6 a.m. to 12 p.m., then from 2:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. The departure from Le Pecq took place 45 minutes later. But this precarious operation improved a few months later with the laying of a second track in 1838. The same year, the first stations at Nanterre and Chatou were opened, then two others at Rueil and Colombes in 1844.[13] Listed on the stock exchange, the share price of the company operating the line from Paris to Saint-Germain quickly doubled: it rose to 1,072 francs in 1838.[14] The atmospheric railway The development in England of atmospheric railway technology made it possible to envisage building a steep extension from Le Pecq to Saint-Germain. This system in fact separated the traction effort from the adhesion. On 5 August 1844, a law made available a credit of 1,800,000 Francs for the testing of an atmospheric railway.[15] On 10 September and 20 October 1844, agreements were signed between the Minister of Public Works and the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Saint-Germain for the test to take place between Nanterre and the Saint-Germain plateau, in return for an extension of the line between the terminus of Le Pecq and said plateau. These agreements were approved by a royal ordinance on 2 November following.[16] Work on the extension began in 1845.[17] It consisted of building a wooden bridge over the Seine, followed by a twenty-arch masonry viaduct. The route reached the centre of Saint-Germain-en-Laye by passing under the terrace of the château, through two successive tunnels. The terminal station was built in a trench in the château park, breaking the symmetry of Le Nôtre's flowerbeds in the process, but without apparently provoking any protest. The line was thus extended on 15 April 1847 over 1.5 km (0.93 mi), with a 3.5% gradient, considerable for a railway.[13][18] On the way there, the ascending track has a cast iron tube 63 cm (25 in) in diameter, split at its top, but made watertight by two leather lips. It contained a piston attached to the chassis of a steering wagon, spreading the lips of the tube which closed after its passage, allowing it to be sucked in and made to climb the slope. Pumps created a vacuum in the tube, which attracted the piston and pulls the steering car,[19] which pulled the cars like a classic locomotive. These pumps were operated by two steam engines with a power of two hundred horsepower, placed between the two Saint-Germain tunnels. They produced an air flow of 4 m3 (140 cu ft) per second, sufficient to move a convoy uphill at a speed of 35 km/h.[13] On the way back, the train descended by simple gravity to Le Pecq, where the steam engine from the outward journey awaited to pull it to Paris. The system works as best it can, but rapid technical progress with the arrival of more powerful locomotives means it is abandoned in 1860 for a classic steam traction by simple adhesion. From 3 July 1860, a locomotive[20] of class 030 is placed at Le Pecq at the end of the train and provides the push to assist the leading engine. This operation continues for more than sixty years until the electrification of the line.[13][21][22]

Steam traction The demographic growth of the towns crossed by the line led to the creation of new stopping points. Vésinet station opened in 1859 when construction of this new town began with the subdivision of the forest. That year, the line was served by 16 daily round trips, with one train per hour, carrying 2,300,000 passengers. Twenty years later, there were 4,200,000, with twenty-two round trips per day. The journey time from end to end reached 47 minutes, but was reduced to 33 minutes by the creation of semi-direct trains from Paris to Rueil-Malmaison.[23] Contrary to what Pereire had planned, the line was not extended beyond Saint-Germain-en-Laye, but several other lines branched off at points along its route. First, the Paris-Saint-Lazare–Versailles Right Bank line, built in 1839, branched off at Asnières to follow the left bank of the Seine to Saint-Cloud. Then, the Paris–Le Havre railway, opened in 1843, branched off at Colombes and headed towards Poissy, Mantes-la-Jolie and Rouen. With the constant increase in the number of trains, the modest station at Place de l'Europe quickly became too small. In 1843, the tracks were extended 300 m (980 ft) to the south, along rue d'Amsterdam, and a new station was built on rue Saint-Lazare, from which it took its name.[23] Other lines in turn branched off this common trunk, the Argenteuil line (Paris-Saint-Lazare – Ermont-Eaubonne railway in 1851, from a junction at Asnières, then the Auteuil line (Pont-Cardinet – Auteuil-Boulogne railway) in 1854, which branched off in the Batignolles district of Paris. All were created by separate companies, which had to run their trains on the same tracks, despite successive additions, and coexist in the same terminal station, which posed increasing operational problems. In order to put an end to this, on 30 January 1855, the Paris to Saint-Germain, Paris to Rouen, Rouen to Le Havre, West and Paris to Caen and Cherbourg companies signed a merger agreement. This was approved by an agreement signed on 2 February and 6 April between the Minister of Public Works and the Companies. Finally, the merger was approved by an imperial decree on 7 April 1855.[24] This merger gave birth to the Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Ouest. Thanks to its many lines finely serving the western suburbs of Paris, the Saint-Lazare station then became the most important in the capital in terms of its traffic, which doubled every twenty to twenty-five years for more than a century.[23] The overlapping of the main line and suburban flows led to the creation of a new route by the Compagnie de l'Ouest in order to better separate the flows: in 1892, the Saint-Germain line was diverted via Bécon-les-Bruyères and La Garenne, and no longer served Colombes-Embranchement (Bois-Colombes). The following year, zone service was introduced, with the creation of intermediate termini where small suburban commuter trains terminated, with trains serving the outer suburbs running direct from Paris to these partial termini.[25] Electrification of the WestFrom the end of the 19th century, the Compagnie de l'Ouest considered the electrification of its suburban lines. Indeed, the poor acceleration of steam locomotives and the inevitable movements of locomotives in terminal stations, despite improvements in operational procedures, limited traffic on the lines.[25] In addition, the steam operation of suburban lines with dense traffic led to a growing deficit. But in 1908, the critical financial situation of the Company led to its purchase by the State, which took over the operation of the lines on 1 January 1909. The electrification of the line was carried out gradually from 1924 to 1927, with 750 V DC supply by third rail (top contact). Electrification reached Bécon-les-Bruyères on 27 April 1924,[26] Rueil-Malmaison on 27 June 1926,[26] and finally Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 20 March 1927.[26] The power supply was converted to catenary power supply system in October 1972, losing its third rail, for the section from Nanterre-Université (new name of La Folie station) to Saint-Germain, but at 1,500 V DC with a view to its incorporation into the RER line A operated by the RATP. The section from Paris-Saint-Lazare to Nanterre-Université was re-electrified by catenary at 25 kV AC at 50 Hz on 15 September 1978.[26] and in turn lost the 750 V direct current electric rail. The Nanterre-Université station has no point of contact between the two types of current, although a non-electrified exchange track exists between the two halves of the line. Integration into RER line A During the 1960s, it was planned to integrate the western section of the Saint-Germain line into the new East-West line of a regional metro. This modification would make it possible to reduce the number of services provided from Saint-Lazare station, which was then close to saturation. The integration of the section from Nanterre University to Saint-Germain-en-Laye required major adaptation work, in particular re-electrification by catenary using 1,500 volts DC for the circulation of MS 61 rolling stock. All the stations on the section are also rebuilt.[27] On 1 October 1972, this section was transferred by the SNCF to the RATP to be incorporated into RER line A. The original route was then split in two: the first part, from Saint-Lazare station to Nanterre-Université station now formed the Saint-Lazare suburban network which would later become part of Transilien Line L, while the second part, from Nanterre-Université (then called "La Folie-Complexe universitaire") to Saint-Germain-en-Laye station became part of RER line A.[28] In 2017, during preventive archaeological excavations as part of an urban planning project by the Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (INRAP) researchers, the remains of the base of the original Pecq station, the former terminus of the line in 1837, were unearthed. During eleven weeks of meticulous research on approximately 1,600 m2 (17,000 sq ft), the archaeologists uncovered not only building structures, but also the turntable for reversing locomotives, buttons belonging to the staff, as well as ceramic tableware decorated with gilding, used in the station restaurant.[29][30] The lineRouteThe line originates at the Gare de Paris-Saint-Lazare. It heads northwest, serving the stations of Pont-Cardinet (Paris XVII) and Clichy–Levallois, before reaching Asnières. The route turns southwest and serves the stations of La Garenne-Colombes, then Nanterre-Université, the terminus of the line since 1972. The historic line, the final section of which was incorporated into the RER A in 1972, continued towards Nanterre-Ville, Rueil-Malmaison, then Le Pecq. This route was extended in 1847 to Saint-Germain-en-Laye.  The line intersects the meanders of the Seine and crosses the river three times at Asnières, Chatou and Le Pecq. Its profile is relatively flat, except in the terminal section between Le Pecq and Saint-Germain-en-Laye on a marked ramp over 2 km (1.2 mi). On this last section, it has an underground passage, which allows it to pass under the terrace of the Château. StructuresThe four main structures on the line are the Asnières railway bridge, the Chatou railway bridge, the Pecq railway viaduct and the Saint-Germain-en-Laye tunnel. It is also crossed by numerous road bridges such as the Pont des Couronnes. EquipmentFrom Paris to Nanterre-Université, the line is electrified like the entire Saint-Lazare network at 25 kV-50 Hz single-phase,[31] equipped with Block automatique lumineux (BAL), a form of automatic block signaling using coloured light signalling,[32] Contrôle de vitesse par balises (KVB; speed control by beacons)[33] and a ground to train radio link without data transmission with identification.[34] From Nanterre-Université to Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the line is electrified like the entire RER RATP network at 1,500 V DC, also controlled by the RATP automatic light block (BAL) and by KCVB. Speed limitsThe line speed limits in 2014 in the SNCF zone for railcars and V 140 trains in odd directions are indicated in the table below, but trains of certain categories, such as freight trains, are subject to lower limits.[35]

References

Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||