|

Otford Palace

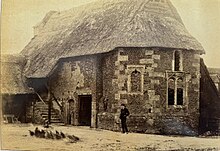

Otford Palace, also known as the Archbishop's Palace, is situated in Otford, a village and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England. The village is located on the River Darent, which flows northward down its valley from its source in the North Downs.  Since 2019, the site has been maintained and restored by The Archbishop’s Palace Conservation Trust (APCT) under a 99-year lease from Sevenoaks District Council.[1] HistoryRoman periodA fragment of a Chi Rho monogram, painted on Roman wall plaster, was recovered from the fill of a Norman drain that was infilled when the medieval manor was enlarged by Archbishop Robert Winchelsey in the early fourteenth century. This material originated from the nearby Church Field Roman Villa and suggests that Otford was a site of Christian worship in Roman Britain.[2][3] Saxon DaysIn 776, Offa, King of Mercia, fought the Kentish Saxons at the Battle of Otford. In 791 (or possibly the preceding year), Offa granted lands at Otford to Christ Church Canterbury (referred to as the 'vill by the name of Otford').[4] This was a highly significant gift, as it meant that the Monastery of Christ Church Canterbury, and subsequently the Archbishops of Canterbury, became the Lords of the Manor of Otford. While the size of this land was not recorded, further gifts were made in 820 and 821. The first of these was by King Coenwulf of Mercia, and the second by Ceolwulf I, his brother and successor, who donated lands at Otford bordering the eastern bank of the River Darent between Shoreham and what is now Bat and Ball.[3] The second charter, in which Ceolwulf grants Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury, five plough lands consisting of two groups—one lying northwest of Kemsing and the other to the southwest—can be found in the British Museum.[5]   A large, moated manor house was built here and subsequently enlarged over the next 600 years by 52 archbishops. Until 1537, the palace was part of a chain of houses belonging to the Archbishops of Canterbury. In 1500, the Court Roll described Otford as "one of the grandest houses in England." High Middle AgesThe estate was granted lands extending from the Thames to the Sussex border, thereby increasing the importance and size of the manor. In 1086, according to the Domesday Book, the manor had six water mills and a large demesne farm worked by serfs. Over time, their obligations gradually shifted to monetary payments, leading to an improvement in their lives and status.[3] The manor was surrounded by a moat from early times, and the island was enlarged three times, including during Tudor times. The manor itself was expanded by Archbishop Robert Winchelsey (1294-1313), who died there. He also constructed a magnificent chapel. Otford Manor became a regular residence for the archbishops, among several others in the diocese, and was possibly their most valuable possession. The Archbishop travelled with a large retinue according to a set timetable.[3] Archbishop Thomas Becket was a regular visitor before his exile and martyrdom in 1170. Becket's Well is located in the grounds of Castle House, 150 yards east of the Palace site. Edward III spent Christmas there in 1348, during a sede vacante, when it was under the control of the Crown.[3] Palace of Archbishop Warham It appears from sporadic records that by the time of Henry VIII’s accession, Archbishop William Warham had begun remodelling and extending the medieval house.[6] In 1514, Archbishop Warham, frustrated by the City Fathers at Canterbury who refused to allow him to build a new palace there, commenced work in Otford. According to his friend Erasmus, "he left nothing of the first work, but only the walls of a hall and of a chapel."[7] He added the North, East, and West Ranges around a great courtyard. The enlarged palace predated Cardinal Wolsey's Hampton Court and was only slightly larger in extent. Visitors to the palace included Erasmus, a close friend of William Warham, and Hans Holbein the Younger. Warham received Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio here in July 1518, as he was en route to London to confer the title of cardinal a latere upon Wolsey. In May 1520, King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon travelled up the Darent Valley from Greenwich Palace with an enormous retinue and stayed overnight on their way to the Field of the Cloth of Gold. A survey (c. 1537) recorded that the bridge led to the forebay or forefront of the Gallery, well constructed of freestone with large bay windows extending outward, following a uniform plan along the entire northern part of the moat. It was described as very pleasant to the view and outlook. The hall was surrounded by galleries, towers, and turrets of stone, and the chapel was embattled and partly covered with lead. However, in 1537, Henry VIII forced Archbishop Thomas Cranmer to surrender both Otford and Knole to the Crown.[6] Archbishop Cranmer's secretary, Ralph Morrice, recorded around 1543: "I was by when Otteford and Knole was given him. My Lord Cranmer mynding to have retained Knole unto himself, saied, that it is too small a house for his Majestie. "Marye" (saied the King), "I had rather to have it than this house (meaning Otteford), for it standith of a better soile. This house standith lowe and is rewmatike like unto Croydon where I colde never be without sykeness. And as for Knole it standith on a sounde parfait holsome grounde. And if I should make myne abode here as I do suerlie minde to do nowe and then, I will lye at Knole and most of my house shall lye at Otteford." And so my this means bothe these houses were delivered upp unto the Kings hands, and as for Otteford, it is a notable greate and ample house, whose reparations yerlie stode my Lordew in more that wolde thinke." Elizabeth I showed relatively little interest in the palace, although she did stay at Otford in July and August 1559.[6] The Sidney family became Hereditary Keepers of the Palace under Elizabeth. They held a lease on the Little Park and had long desired to acquire the estate. In 1596, Robert Sidney offered to build a house at his own expense where the Queen could dine, as she had under Sir Henry Sidney in July 1573. Elizabeth eventually sold it to the Sidney family in 1601, as she needed funds to support her troops in Ireland. The Sidneys converted the western side of the North Range into their private quarters. Viscount Lisle sold the property in 1618-19, after first disparking the Great Park.[6] His use of the buildings in the North Range as a keeper's house ensured their survival, whereas the rest of the palace was demolished for its materials. The North Range was abandoned, probably around the middle of the eighteenth century.[6] Farm buildings and afterThe Great Park was divided into three farms. The northern farm became known as Place Great Lodge Farm, later Castle Farm. The Great North Range was eventually converted into farm buildings. In the 18th century, the northern cloister was transformed into a single-storey thatched-roof cowshed, while the remains of the Gatehouse were repurposed as a barn.  In 1761, the North East Tower of the Palace was demolished, and the stonework was transported to Knole, Sevenoaks, where it was used to build Knole Folly, located to the south-east of Knole House. The principal surviving remains are the North-West Tower, the lower gallery (now converted into cottages), and part of the Great Gatehouse. There are additional remains on private land, and a section of the boundary wall can be seen on Bubblestone Road. The entire site, covering about 4 acres (1.6 ha), is designated as an ancient monument.[8] The village also contains related buildings, including a wall in St Bartholomew's Church dating from c. 1050. Otford Palace todayNorthwest TowerThe three-storey corner towers each have a high-status accommodation room on every floor. There is a stack of garderobes on each level. The flat leaded roof was accessible by a staircase that ended in a small turret. The upper two rooms were panelled, while the lowest storey was plastered. Each chamber had a flat ceiling.[6] Cloisters  The Inner Courtyard was surrounded on three sides by galleries. The northern cloister, with eleven now-filled-in brick arches above a ragstone plinth, is a small remnant and is located between the Northwest Tower and the Gatehouse remnant. Some arches now contain modern windows. Originally, at first-floor level, there was a gallery with a tiled roof, possibly with a timber frame. This gallery formed a circuitous walkway with glazed windows, allowing exercise in poor weather or after dark, and providing a space for discreet conversation. This may have been England's first galleried house.[9] There do not appear to have been any original windows in the outer wall of the galleries.[6] Gatehouse   At the eastern end of the cottages is a large single-storey building with a tiled roof and stone mullioned windows. This is the remains of the western half of the Great Gatehouse. This great tower was probably five storeys high, crenellated, and crowned with flat lead-covered roofs. It served as the grand entrance to Archbishop Warham's Palace. Above it would have been an arch. At the southern end, the massive carved stone door jambs are still in position, attached to the inner end of the gatehouse wall. There was probably a second outer gate at the northern end, but no trace of it is visible today. The surviving ground floor of the western half of the Gatehouse was originally one large chamber with a porter's lodge at the front. It had adjacent doors, one of which remains intact, while the other has an enlarged but original rear arch.[6] An external stair at the south end led to a two-room lodging on the first floor, flanking a central room over the gate passage.[6] The gatehouse features late Gothic details.[6] It is documented to have had three roofs, suggesting there were likely three storeys, with a single tall central room.[6] Cliff Ward, in his guide to the palace, suggests that there may have been four or five storeys in the gatehouse.[3] It was similar to, but less grand than, those at Lambeth (1490) and Hampton Court.  SignificanceOtford Palace is of exceptional significance for: • The evidence it provides regarding the form and architectural character of one of the outstanding buildings of early 16th-century England. • Its archaeological potential to yield much more information about the building, particularly on the moat island and its medieval predecessors. Otford Palace is of considerable significance for: • The evidential value of the adaptation of the north-west range by the Sidney family. • Its ability to illustrate the form and scale of a late medieval archiepiscopal palace, despite its fragmentary survival. • The aesthetic qualities, both designed and fortuitous, of the north range building in its open space setting. • The contribution it makes to the character and appearance of the Otford Conservation Area. • The insight it provides into the character and ambition of Archbishop Warham. Otford Palace is of some significance for: • Illustrating, especially with the archive material, the struggle to conserve historic places during the 20th century. • Its contribution to the identity of Otford and its community today. The Palace is now under the care of the Archbishop's Palace Conservation Trust.[10] References

External links

|