|

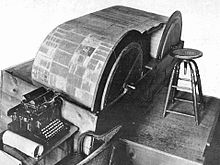

Orville Ward Owen Dr. Orville Ward Owen (January 1, 1854 – March 31, 1924) was an American physician, and exponent of the Baconian theory of Shakespearean authorship. Owen claimed to have discovered hidden messages contained in the works of Shakespeare/Bacon. He deciphered these using a device he invented called a "cipher wheel". The alleged discoveries were published in Owen's multi-volume work Sir Francis Bacon's Cipher Story (1893–95). MethodOwen's "cipher wheel" was a device for quickly collating printed pages from the works of Shakespeare, Francis Bacon, and other authors, combining passages that appeared to have some connection with key words or phrases. Owen described this as the word cipher. The cipher consisted of two large wooden cylinders, 36 inches in diameter and 48 inches long, on which a one thousand long strip of canvas was wound around.[1] The canvas had on it pasted the works of Shakespeare as well as samples by Christopher Marlowe and other contemporaries. When the wheels turned, key words were highlighted.[2] The method was examined by cryptologists William and Elizebeth Friedman, who conclude that it has no cryptographic validity.[3] In addition, Dr. Frederick Mann, a close friend of Owen, published a severe critique soon after Owen's book first appeared. Mann wrote that Owen's method means that "we are asked to believe that such peerless creations as Hamlet, The Tempest, and Romeo and Juliet were not prime productions of the transcendent genius who wrote them, but were subsidiary devices which Bacon designed for the purpose of concealing the cipher therein." He also noted that Owen and his assistants gave themselves considerable freedom in choosing and altering passages as they saw fit, even though the cipher-text was supposed to be identified by keywords; "in one instance the keyword is 47 lines away from the quotation taken, and in a large number of instances it is not even to be found on the same page".[4] Owen drew on the works normally attributed to Bacon, Shakespeare, Robert Greene, George Peele, Edmund Spenser and Robert Burton, all of which he believed had been written by Bacon. Findings Owen's book Sir Francis Bacon's Cipher Story (1893-5) stated that Queen Elizabeth I was secretly married to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who fathered both Bacon and Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, later ruthlessly executed by his own mother.[5] This was the basis for what became known as Prince Tudor theory. This secret history of the Elizabethan period was communicated by Bacon through encoded passages in his own works and the many others he had written attributed to other authors. Bacon's hidden messages are communicated in blank verse in the form of a question and answer session, in which a voice asks Bacon questions and receives long verse replies. When the queen discovered that her son had written Hamlet, Bacon's movements were restricted "circumscribing the free scope of that mighty intellect, and forcing the hiding of its best work under masks and cipher, only to be revealed three hundred years later".[6] It was also revealed that Bacon himself discovered his brother's treasonable plot, and that Romeo and Juliet is the story of Bacon's romance with the Queen of France, Margaret of Valois.[6] Elizabeth confessed that Bacon was her son on her deathbed, but she was poisoned and strangled by Robert Cecil to prevent her proclaiming Bacon her successor. Owen also uncovered two new plays by Bacon, The tragical historie of our late brother Robert, earl of Essex and The historical tragedy of Mary queen of Scots. Owen was led to the belief that original manuscripts were hidden in iron boxes buried beneath or close to the River Wye at Chepstow Castle. After a fruitless search in caves near the castle in September 1909, he returned late the following year and excavated the river bed a few hundred yards above the castle in the belief that a rift in the river bed held a vault containing 66 lead-lined boxes. The search attracted widespread media interest, and up to 24 men were employed to dig out the mud and shore up the sides. Although Owen failed to find any evidence of the vault or boxes, he did discover the remains of a Roman bridge near the castle, and a previously unrecorded medieval water cistern.[7][8] Owen died a "bedridden almost penniless invalid", full of regret for sacrificing his career, reputation and health on the "Baconian controversy" and warning admirers to learn by his example and avoid it.[7] His theories were later developed by his assistant Elizabeth Wells Gallup. Owen's cipher wheel was discovered in a warehouse in Detroit[9] by Virginia Fellows, a 20th-century supporter of Owen's theory, who presented it to her publisher. Her book The Shakespeare Code was published in 2006 shortly after her death. Footnotes

Further reading

|