|

Operation Écouvillon

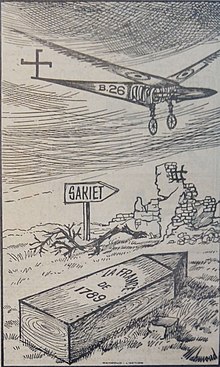

Operation Écouvillon, also known as Operation Ouragan or Operation Teide, was a joint military operation conducted by France and Spain against the Moroccan Army of Liberation during the Ifni War. The operation took place from 10 to 24 February 1958 in the northern Sahara, which was under Spanish control. Its primary objective was to suppress Saharan resistance and secure Spanish dominance over the territory. Planned in secrecy, Operation Écouvillon was significant in understanding the broader context of Western Sahara. It occurred within a complex geopolitical landscape, as the operation took place in a strategically significant territory claimed by Spain and various independence movements that had complicated relationships with the newly independent Morocco at the time. The decolonization processes in Algeria and Mauritania further complicated the political context. Additionally, many insurgents from the Moroccan Army of Liberation received support from members of the Berber peoples and tribes in the Sahel region. The Franco-Spanish operation was deemed successful, with Spain retaining control over the Spanish Sahara. France was able to further its interests in the region and temporarily gain the support of the Reguibat tribe. Another outcome of the operation was Spain's return of Tarfaya to Morocco. Following the operation, Morocco adopted the doctrine of Greater Morocco, among other strategic decisions. The operation also played a significant role in transferring military power during Mauritania's path to independence. BackgroundMorocco's independence and decolonizationIn 1956, Morocco gained independence, but some territories in what is now Western Sahara, including Ifni, remained under Spanish control. The Spanish occupation of Ifni led to violent clashes between Spanish forces and Saharan resistance fighters starting on 10 April 1957.[6] At the same time, resistance against French colonial rule emerged on the Mauritanian side, led by the Mauritanian Berber tribe of Reguibat, with support from nearly 1,200 Moroccan soldiers from the Moroccan Army of Liberation (AL). This combined group later renamed itself the Mauritanian Liberation Army.[7] This situation led to a disagreement between the King of Morocco, who was hesitant to fully commit to the liberation of these territories, and some resistance fighters from the Moroccan Army of Liberation (AL), who were unwilling to join the royal forces. This dissident faction believed that these territories should be liberated independently. Instead of integrating into the Royal Armed Forces, the dissidents joined the Sahrawi resistance fighters who were actively fighting against the Spanish military.[8] Despite these differing viewpoints, the Sahrawi resistance, primarily led by dissidents with the support of local tribes, received partial funding from the Moroccan monarchy,[9] which viewed the struggle against Spanish occupiers favorably. The composition of the Moroccan liberation army was complex; Camille Evrard describes it as a 'multiform' army that included dissidents from the national liberation army who refused to join the Royal Armed Forces, as well as members of Saharan tribes from the Spanish Sahara and what is now Mauritania, which was then part of French West Africa.[10] By the end of August 1957, Spanish forces were forced to withdraw from several towns in the region, including Smara,[11] which fell under Moroccan control.[11] Spain subsequently requested assistance from French forces, leading to the deployment of Operation Ecouvillon. This operation was carried out under secret agreements, although its implementation required a pretext for French intervention.[12] The operation took place within the larger context of the decolonization of North Africa, a factor that likely influenced the decisions of the key actors involved.[7][13][14] Geography The operation was conducted mainly in the Rio de Oro region, extending to Bir Moghreïn in Mauritania. Key locations involved in the operation included the towns of Es-Semara, Saguia el-Hamra, Laâyoune, Ifni, and Tarfaya. The region is characterized by a desert climate, featuring sparse vegetation with occasional depressions and predominantly shrubby plant life. The harsh environmental conditions of the desert played a significant role in shaping the strategies and outcomes of the military operation.[7] The idea of "Greater Morocco" and Moroccan demandsThe Moroccan claims to the territory involved in the operation were an important factor in the French rationale for participating. These claims are closely linked to the doctrine of Greater Morocco, which was developed after Morocco's independence by Allal al Fassi. Al Fassi argued that Morocco's independence was incomplete because large portions of its "historic" territories remained under foreign control.[15] Initially popular within the nationalist Istiqlal party, the doctrine eventually gained broader acceptance, including within the Moroccan monarchy, particularly after the actions of the Army of Liberation in the Spanish Sahara and what is now Mauritania. In 1958,[15] the Moroccan government officially adopted the concept of Greater Morocco as part of its national doctrine. Allal al Fassi also maintained that Western Sahara, which had previously been under Almoravid rule,[15] should be included within Greater Morocco's boundaries, further bolstering Morocco's territorial claims in the region. In 1956, the Royal Armed Forces (FAR) were established and placed under the command of Crown Prince Hassan II. Unlike the Moroccan Liberation Army, the FAR was primarily composed of Moroccan goumiers and French officers. Hassan II aimed to integrate the liberation army into the FAR, while the Istiqlal party, led by Mehdi Ben Barka, sought to maintain control over the Army of Liberation, viewing it as a critical tool for continuing the struggle against colonial powers and advancing the concept of Greater Morocco. To avoid integration into the FAR and continue the armed struggle for Greater Morocco, some troops from the liberation army were stationed in southern Morocco. This strategy was successful, with the AL-Sud becoming the only branch of the Army of Liberation that had not joined the FAR by 1956.[15] This branch, working in collaboration with local Berber tribes, led the resistance against colonial rule.[14] In France, Operation Écouvillon was presented as a necessary action to counter perceived "Moroccan expansionism."[14] This narrative was communicated to the Mauritanian population, then under French control, as well as to the broader international community.[14] Geopolitical background On the Spanish side, maintaining control over the entire Spanish Sahara is a significant political issue. The strategic importance of the Spanish presence in the region, along with the discovery of significant natural resources, has contributed to the relevance of the Sahara for Spain. In the late 1940s, Spanish geologist Manuel Alia Medina discovered phosphate deposits near Bou Craa,[16] prompting the Spanish government to commission geological surveys in the area, which were conducted by the Spanish Institute of Geology.[17] These surveys, initiated during Franco's regime, confirmed the existence of large deposits of pure phosphate and indicated the presence of oil. However, Spain faced challenges in exploiting these resources due to logistical limitations.[17] Despite this, Spain was hesitant to allow the newly independent Morocco to utilize these resources. Meanwhile, Morocco maintained a diplomatic appearance towards Spain while reportedly providing financial and military support to insurgents in the Spanish Sahara, leading to a series of attacks against Spanish forces.[17] At the French level, Operation Écouvillon had several main objectives. The primary aim was to address concerns regarding Morocco's expansionist ambitions, particularly its interest in the Mauritanian Sahara, which was then under French control.[13] Additionally, the operation was a response to the activities of the ALM (Army of Liberation Mauritanian ), composed of members from the Moroccan AL and Berber tribes such as the Reguibat, who were conducting armed actions in the Mauritanian Sahara. France sought to prevent these actions,[7] as there were worries that pro-independence sentiments could spread to sub-Saharan territories under national control.[14] The rising independence demands among Sahelian populations under the French administration, encouraged by the Moroccan Army of Liberation,[18] further motivated the operation. General Burgund’s policies were instrumental in making this operation feasible. After World War II, French West Africa, which included the area of modern-day Mauritania, faced a troop shortage, with the National Liberation Army of Algerian and the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces outnumbering French forces. In a 1957 communication to the Ministry of Overseas France, General Burgund noted that the military presence in French West Africa was limited to about 20,000 personnel.[13] The Governor of Mauritania, Albert-Louis Mouragues, supported the request for additional military resources, citing fears of potential Algerian independence movements and Moroccan expansionism.[13] Consequently, in May 1957, Mauritania received military reinforcements aimed at ensuring security in the region.[13] This reinforcement was seen as a key step in allowing French companies to access available resources and make necessary investments.[12][14] France's military support for Spain was therefore influenced by a desire to safeguard its financial interests in the region while also preventing the proliferation of independence movements into sub-Saharan Africa.[19] Towards the end of 1957, the Moroccan Army of Liberation (AL) was involved in conflict with the monarchy and its former allies from the Reguibat tribe. The Reguibat tribe claimed that the Moroccan contingent within the AL was trying to dominate their territory and military resources. As a result, the Reguibat, who were already engaged in guerrilla warfare against the French military, formed an alliance with the French forces to counter the Moroccan AL troops.[7] Spanish wave of defeats 1957-January 1958After gaining independence, Morocco provided financial and military support to the Sahrawi insurgents and the AL-Sud in their struggle against Spanish colonial forces. As a result, between 1957 and 1958, the Spanish army in Western Sahara experienced a series of defeats against both Sahrawi troops and Moroccan forces from the AL-Sud. The main aim of the Sahrawi attacks during this period was to regain control of the Ifni strip and the town of Ifni.[17]  On 23 November 1957, Moroccan forces cut the telephone lines, allowing insurgents to launch a series of coordinated attacks on strategic locations, including the airfield and arms depots, as well as various points within the town. These locations were defended by the 3rd Infantry Battalion, the 3rd Artillery Battery, and a Saharan police unit, totaling around 1,500 Spanish soldiers and 500 Saharan police officers.[17] The attackers maintained an intense artillery barrage on the town for several hours, followed by an assault involving approximately 1,200 rebels armed with automatic weapons.[17] The Spanish forces reported 55 fatalities and 128 injuries, with seven individuals listed as missing. The Moroccan insurgents also faced significant casualties and, in the weeks that followed, shifted their focus to smaller attacks against minor Spanish outposts, particularly targeting Taliouine.[17] The Taliouine fortress was defended by a platoon of Tiradores and a platoon of Sahrawi police officers, with support from the local Bedouin community. However, by 25 November 1957, the situation had worsened, necessitating the deployment of rescue units. This relief force consisted of personnel from the Legion, parachutists, and an 88-millimeter artillery battery. Although the operation was successful in preserving the outpost, the defenders incurred significant casualties, leading to their withdrawal from the fortress and subsequent relocation to Ifni. Other outposts faced similar difficulties, with Spanish forces determined to maintain their positions despite the considerable losses.[17] By 9 December 1957, the Spanish had lost all their outposts and were compelled to retreat towards Sidi Ifni, which soon became fully surrounded by Moroccan troops.[17] On 12 and 13 January 1958, insurgent forces attacked the town of Laâyoune, which was defended by the 13th Battalion of the Spanish Legion. Despite having a numerical advantage, the insurgents were ultimately unsuccessful and retreated. Spanish troops then pursued the insurgents but were ambushed near Dcheira El Jihadia. During the ambush, Captain Jauregui was mortally wounded. After the attack concluded, the Spanish forces were forced to withdraw, engaging in defensive operations that resulted in 37 fatalities and 50 injuries.[17] The challenging military circumstances led the Spanish to agree to Operation Écouvillon, a collaborative initiative with the French army.[17] Operation preparationFrance and Spain historically sought to conduct joint operations to maintain control over the Saharan territories, particularly amidst rising tensions in the region. In 1957, multiple negotiations took place between the two countries aimed at reaching an agreement for a coordinated response to the insurgent threats. However, these discussions ultimately proved unsuccessful. General Burgund, the French general responsible for leading the negotiations, was eager to formalize an agreement quickly. In contrast, his Spanish counterpart, General Mariano Gómez-Zamalloa, showed hesitance to proceed with a joint operation.[20] The situation escalated with the offensives launched by the Armée de Libération Nationale-Sud (ALN-South) in the Spanish-held Saharan territories, compelling Spain to pursue a resolution through diplomatic means.[21]  On 14 January 1958, General Burgund convened with the Spanish generals overseeing operations in the Spanish Sahara to devise a comprehensive action plan. This meeting yielded positive results, and a follow-up meeting was arranged for 24 January 1958 in Dakar, where the two parties agreed on a detailed plan of action. The commencement of the operation was tentatively set for 4 February 1958.[21] The action plan outlined a clear division of the operation into two phases. The first phase focused on the destruction of the majority of ALN forces, primarily concentrated in Es-Semara and Saguia el-Hamra. Following this initial phase, the second phase aimed to neutralize the remaining resistance in the Rio de Oro region through a coordinated joint operation. This phase involved French forces stationed at Fort-Trinquet, Fort-Gouraud, and Port-Étienne, working in tandem with Spanish forces positioned at Villa Cisneros and Laâyoune.[13] This collaborative strategy reflected a concerted effort by both nations to address the security threats in the Sahara while attempting to consolidate their influence over the region. France was eager to move forward with the joint operation in the Sahara but insisted that all operational details remain confidential. Despite this emphasis on secrecy, General Burgund worked diligently to ensure the success of the mission. On 31 January 1958, he established an "operational political and psychological action bureau," a specialized military unit focused on conducting psychological warfare. Such units were commonly employed by colonial powers during decolonization conflicts to influence local populations and bolster support for military actions.[22] In addition to this bureau, two significant elements underscored the French army's intention to organize the operation with the backing of the Mauritanian Saharan population. The first was the enlistment of regular Saharan camel troops. The second involved the formation of partisan units composed of local nomads, organized along tribal lines. These local forces were crucial for navigating the challenging terrain and gaining the trust of the nomadic communities.[14] From 31 January to 4 February 1958, the French Air Force engaged in active propaganda efforts, distributing leaflets over the targeted villages to prepare the local population for the operation.[21] However, the operation could not commence as planned on 4 February 1958 due to delays caused by the Spanish troops, which stemmed from various logistical challenges. A notable issue was the delivery of drinking water, which was initially dropped into the open sea in jerrycans and subsequently recovered by the Spanish forces as the tide receded.[23] Furthermore, the Spanish troops faced difficulties with their uniforms, as they were equipped with winter attire unsuitable for the harsh desert conditions, while the French forces had appropriate outfits for the environment. In terms of food supplies, the French troops had access to a range of high-nutritional-value items, including fruit juices, designed to combat dehydration and prevent avitaminosis in the arid climate.[23] In contrast, the Spanish soldiers relied on standard supplies, which included rice and dried meat, highlighting a disparity in logistical preparation between the two forces.[21] This logistical mismatch contributed to the challenges faced by the Spanish contingent as they prepared to embark on the operation alongside the French. The operational plan for the joint French-Spanish military action called for Spanish forces to occupy the Drâa region.[21] However, heavy rainfall rendered the area impassable, necessitating a redeployment of those troops to alternative locations. To minimize the risk of clashes with the Moroccan Armed Forces (MAF) and ensure Morocco's neutrality in the conflict, geographical limits defining the area of operation were carefully established.[13] While most conditions for the operation were in place, one critical issue remained: France needed to articulate a plausible rationale for deploying troops to engage with the AL. Since the conflict was primarily Spanish, France faced the challenge of justifying its involvement to both the international community and the French Socialists, who were largely opposed to forming an alliance with Francoist Spain.[13] Thus, maintaining secrecy around the operation was of utmost importance.[19] To address this challenge, the French government provided a pretext for the military action, citing a skirmish between Mauritanian goumiers and AL insurgents.[19] This justification aligned with the broader narrative propagated by French authorities since 1957 regarding Mauritania. This narrative emphasized the potential for instability in the region and the perceived threat of Moroccan expansionism, framing these developments as direct risks to the security of French interests in Mauritania and the surrounding areas.[14] By framing the operation as a necessary response to protect stability and counter expansionist threats, France sought to create an acceptable rationale for its military involvement while also mitigating potential backlash from domestic and international audiences. This strategic communication effort was crucial to facilitating the military cooperation between France and Spain, particularly in light of the complex political landscape surrounding the decolonization process in North Africa.[14] Forces at work, course and resultsForces at workFrance contributed 5,000 personnel, 600 vehicles, and 50 aircraft to Operation Écouvillon, primarily drawn from garrisons in Mauritania under the command of General Burgund. Additionally, France provided logistical support for the 9,000 Spanish soldiers and their 60 aircraft, which were led by General José María López Valencia.[24][25] Several sources report that the Royal Armed Forces of Morocco assisted France and Spain during this operation, aiming to neutralize elements of the Army of Liberation (AL). Mounia Bennani-Chaïbi notes that the Royal Armed Forces were deployed with the goal of "driving the maquisards back."[8] Officer Michel Ivan Louit, who was present during the operation, confirmed the involvement of the Royal Moroccan Forces.[26] Similarly, Caratini corroborated the participation of the FAR in the pursuit of AL dissidents.[18] Notably, during this operation, the Moroccan monarchy deviated from its usual stance by not providing support to the insurgents.[24] While it is difficult to determine the exact number of rebels involved, estimates suggest there were about 12,000 troops.[24] The French forces exhibited significant technical superiority over the Spanish army, which relied on outdated weapons from the Spanish Civil War and had inferior logistical support compared to the French.[24] Regarding the insurgent forces, a French army report indicated that they were positioned in the Saguiea el-Hamra and Adrar Souttouf regions,[7] the latter of which is a mountainous area in Mauritania.[27] The document reported that the insurgent force near Gueltat Zemmour consisted of approximately 600 to 800 personnel, with an estimated 25% comprising Moroccan soldiers under Algerian commander Si Salah.[7] Additionally, the report stated that between 300 and 400 insurgents were present in the central Seguiet region, commanded by a Moroccan general named El Hachmi. In the Mauritanian section of the desert, it was noted that 300 to 400 members were led by Ely Bouya,[7] the chief of one of the Mauritanian Reguibat tribes, along with at least 850 fighters divided into three distinct groups.[7] The course of the operationAlthough the official start date for Operation Écouvillon was set for 10 February 1958, the first French air strikes were conducted on 9 February 1958, with French troops departing from Tindouf and Fort-Trinquet.[24] A total of 68 air sorties were executed, targeting the towns of Tan-Tan and Saguia el-Hamra,[21] where Sahrawi forces were concentrated. These initial strikes resulted in the deaths of nearly 150 Sahrawis, and it has been confirmed that the French army utilized napalm[24] during these operations. Concurrently, the regular Spanish army moved to reclaim the towns of Laâyoune and Tarfaya.[24] The official timeline for the operation spanned from 10 February to 24 February 1958,[7] and it was divided into two distinct phases: the first phase lasted from 10 February to 20 February, while the second phase extended from 20 February to 24 February.  The operation commenced on 10 February 1958, with most of the combat centered around the town of Es-Semara (then referred to as Smara). The initial action, designated Operation Airborne Huracan, involved a collaboration between a Spanish parachute company and the French 7th Parachute Chasseur Regiment (7th RPC) aimed at dislodging the Moroccan Liberation Army from the town.[28] A total of 98 Spanish paratroopers, deployed via French Nord 2501 aircraft, successfully reclaimed control of Smara with the support of French forces stationed nearby.[11] Despite this initial success, French generals adopted a cautious approach, recognizing the significant military advantage held by Franco-Spanish forces while also considering the potential limitations of this advantage in securing local support for the Moroccan AL.[21][23] This cautious stance reflected an awareness of the complex dynamics on the ground, including the need to manage relations with local populations and the risks associated with prolonged military engagement in the region. The operation's outcomes would ultimately shape the future of Franco-Spanish relations in the Sahara and influence the broader context of decolonization in North Africa. In the days that followed the commencement of Operation Écouvillon, the Franco-Spanish coalition achieved significant military victories against the Moroccan Army of Liberation. As the coalition continued its advance, they successfully seized large arsenals accumulated by the Moroccan forces and pushed back the insurgents. French troops, arriving from Mauritania, provided essential reinforcement to the newly landed Spanish forces. From 10 to 20 February 1958, Spanish troops effectively routed the Sahrawi resistance fighters, achieving notable recoveries, including the reclamation of the town of Es-Semara and the surrounding area of Dcheira.[24] This success underscored the effectiveness of the joint operational strategy, demonstrating the military capabilities of the coalition. The second phase of the operation began on 20 February 1958. On 21 February 1958, the coalition neutralized approximately 300 insurgents in the Aousserd region. Despite facing a determined resistance, the combination of superior equipment, coordinated tactics, and the pressure of ongoing defeats led the insurgents to withdraw from key positions.[24] Following these engagements, the coalition successfully secured control of the Aousserd region, leading to a notable decrease in military confrontation. The operation concluded on 24 February 1958, marking a significant achievement for the Franco-Spanish alliance in their efforts to suppress the insurgent activities in the Saharan territories.[7] This operation not only reinforced the presence of Franco-Spanish influence in the region but also had lasting implications for the local political landscape as the dynamics of power shifted in the wake of military engagement. Results of the operation The coalition faced casualties during Operation Écouvillon, with eight Spanish soldiers and seven French soldiers killed, along with 25 French soldiers wounded.[24][29] In contrast, determining the AL's losses proved more difficult, with estimates ranging from a minimum of 132 fatalities to as high as 900.[13][30][31] Additionally, there were 37 injuries and 51 individuals captured among the insurgent forces.[30] In terms of territorial outcomes, Spain managed to recover much of the territory it had lost in 1957,[7] although some members of the local population fled to neighboring countries.[19] The secretive nature of the operation, prioritized by French decision-makers, was notably effective. For instance, the French Air Force's bombing of Sakiet Sidi Youssef just two days prior to the operation's official commencement shifted the international focus onto the event. When the French Minister for Overseas Territories, Gérard Jaquet, visited Atar to discuss Operation Écouvillon—a military endeavor both in resources and objectives—he characterized it as a "police operation."[19] Despite some international media coverage, public interest in the operation remained low. Moreover, as noted by Elsa Assidon, Morocco's official response was notably ambiguous, with the government expressing minimal objections to "French troop movements," further ensuring the operation remained confidential.[19] Struggle for influence In addition to its military objectives, Operation Écouvillon was also accompanied by propaganda and influence-peddling activities aimed at winning the support of the local population, particularly the Berber tribes. The strategic goal of the French army was clear: to foster local allegiance while simultaneously gathering vital intelligence. This was accomplished through various means, including the distribution of leaflets and the provision of food and supplies to residents in the affected areas.[7] The combination of military actions and these softer tactics yielded positive results for the French forces, allowing them to gain support from some segments of the Reguibat tribes.[7] France adeptly used the narrative of Moroccan expansionism and the composition of its troops, which included soldiers from various colonies, to frame the Mauritanians as fighting against Moroccan encroachment alongside the colonized populations.[14] However, as noted by Camille Evrard, the Reguibat tribes that aligned with Mauritania did not constitute a majority.[14] The defeat of the Army of Liberation led to heightened internal tensions between the Berber-speaking sedentary population and the Arabic-speaking nomadic groups. Colonial powers like Spain and France exploited these existing divisions to galvanize the support of the nomadic populations, further complicating the socio-political landscape in the region.[32] OutcomesThe immediate outcome of Operation Écouvillon, alongside Spain's territorial gains, was the retrocession of the Tarfaya region[9] to the Kingdom of Morocco. On 1 April 1958, Spain and Morocco signed agreements in Dakhla—commonly referred to as the Cintra Agreements[33]—as compensation for Morocco's refusal to support the insurgents during the operation.[24] These agreements stipulated that Spain would return the Tarfaya strip to Morocco.[24]  During this period, Ahmed Agouliz, known as Cheikh el-Arab, who was actively engaged in combat with the AL, survived the operation.[34] Following the swift and decisive nature of Operation Écouvillon, the region experienced a period of relative peace, with Sahrawi insurgents refraining from significant military actions for some time. This lull allowed for a temporary stabilization of the situation in the area, as both colonial powers and local populations adjusted to the new dynamics established by the operation and the subsequent agreements.[31] Operation Écouvillon had important implications for the future independence of Mauritania, particularly regarding the political dynamics within the region. The decision by some members of the Reguibat tribe to align with France had noteworthy political ramifications, as this alliance influenced the local power structure. Camille Evrard argues that this event was crucial in the context of the transfer of military authority in Mauritania.[13] The French army aimed to mobilize the local population to defend the territory against a clearly defined adversary, which in this context was the Army of Liberation (AL) and its supporters.[13] Evrard highlights the significance of the Tinketrat rally in April 1958, during which the Reguibat pledged their allegiance to Moktar Ould Daddah, as a direct consequence of Operation Écouvillon.[13] This rally not only reinforced the loyalty of certain tribes to the French but also played a role in shaping the military landscape in Mauritania as the country moved toward independence. The Mauritanian soldiers who participated in the operation became a significant portion of the future Mauritanian Armed Forces' cadres,[14] establishing a foundation for the country's military after it gained independence. Additionally, Evrard identifies Operation Écouvillon as a critical point in the separation of French political and military power in the region. The covert nature of the operation generated notable frustration among French military personnel, as it contradicted traditional military practices and transparency, contributing to discontent within the ranks. This tension underpinned a broader shift in how military authority and political dynamics were evolving in the context of decolonization in Mauritania.[13] Legacy and posterityOperation Écouvillon is indeed regarded as a significant logistical achievement in France, particularly given the challenging conditions under which it was executed, the scale of the forces involved, and the necessity to maintain operational secrecy throughout the operation.[14] The successful coordination and mobilization of both French and Spanish forces, alongside local support, showcased the military's ability to navigate complex circumstances effectively. In recognition of the operation and its impact, the French army produced a film documenting the events associated with Écouvillon. This film served both as a portrayal of the operation's significance and as a means of reinforcing the narrative of French military effectiveness. Furthermore, in 2011, Moroccan filmmaker Rahal Boubrik released a documentary about Operation Écouvillon, utilizing archive footage to provide a retrospective view of the events. This documentary contributes to the historical discourse surrounding the operation, offering insights from a Moroccan perspective and emphasizing the lasting implications of the operation on both Moroccan and Mauritanian histories. Such works reflect the complexity of the narrative surrounding colonial and post-colonial conflicts, as different interpretations emerge from various national and cultural lenses.[35] References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||