|

Odd graph

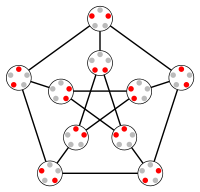

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the odd graphs are a family of symmetric graphs defined from certain set systems. They include and generalize the Petersen graph. The odd graphs have high odd girth, meaning that they contain long odd-length cycles but no short ones. However their name comes not from this property, but from the fact that each edge in the graph has an "odd man out", an element that does not participate in the two sets connected by the edge. Definition and examplesThe odd graph has one vertex for each of the -element subsets of a -element set. Two vertices are connected by an edge if and only if the corresponding subsets are disjoint.[2] That is, is the Kneser graph . is a triangle, while is the familiar Petersen graph. The generalized odd graphs are defined as distance-regular graphs with diameter and odd girth for some .[4] They include the odd graphs and the folded cube graphs. History and applicationsAlthough the Petersen graph has been known since 1898, its definition as an odd graph dates to the work of Kowalewski (1917), who also studied the odd graph .[2][5] Odd graphs have been studied for their applications in chemical graph theory, in modeling the shifts of carbonium ions.[6][7] They have also been proposed as a network topology in parallel computing.[8] The notation for these graphs was introduced by Norman Biggs in 1972.[9] Biggs and Tony Gardiner explain the name of odd graphs in an unpublished manuscript from 1974: each edge of an odd graph can be assigned the unique element which is the "odd man out", i.e., not a member of either subset associated with the vertices incident to that edge.[10][11] PropertiesThe odd graph is regular of degree . It has vertices and edges. Therefore, the number of vertices for is Distance and symmetryIf two vertices in correspond to sets that differ from each other by the removal of elements from one set and the addition of different elements, then they may be reached from each other in steps, each pair of which performs a single addition and removal. If , this is a shortest path; otherwise, it is shorter to find a path of this type from the first set to a set complementary to the second, and then reach the second set in one more step. Therefore, the diameter of is .[1][2] Every odd graph is 3-arc-transitive: every directed three-edge path in an odd graph can be transformed into every other such path by a symmetry of the graph.[12] Odd graphs are distance transitive, hence distance regular.[2] As distance-regular graphs, they are uniquely defined by their intersection array: no other distance-regular graphs can have the same parameters as an odd graph.[13] However, despite their high degree of symmetry, the odd graphs for are never Cayley graphs.[14] Because odd graphs are regular and edge-transitive, their vertex connectivity equals their degree, .[15] Odd graphs with have girth six; however, although they are not bipartite graphs, their odd cycles are much longer. Specifically, the odd graph has odd girth . If an -regular graph has diameter and odd girth , and has only distinct eigenvalues, it must be distance-regular. Distance-regular graphs with diameter and odd girth are known as the generalized odd graphs, and include the folded cube graphs as well as the odd graphs themselves.[4] Independent sets and vertex coloringLet be an odd graph defined from the subsets of a -element set , and let be any member of . Then, among the vertices of , exactly vertices correspond to sets that contain . Because all these sets contain , they are not disjoint, and form an independent set of . That is, has different independent sets of size . It follows from the Erdős–Ko–Rado theorem that these are the maximum independent sets of , i.e. the independence number of is Further, every maximum independent set must have this form, so has exactly maximum independent sets.[2] If is a maximum independent set, formed by the sets that contain , then the complement of is the set of vertices that do not contain . This complementary set induces a matching in . Each vertex of the independent set is adjacent to vertices of the matching, and each vertex of the matching is adjacent to vertices of the independent set.[2] Because of this decomposition, and because odd graphs are not bipartite, they have chromatic number three: the vertices of the maximum independent set can be assigned a single color, and two more colors suffice to color the complementary matching. Edge coloringBy Vizing's theorem, the number of colors needed to color the edges of the odd graph is either or , and in the case of the Petersen graph it is . When is a power of two, the number of vertices in the graph is odd, from which it again follows that the number of edge colors is .[16] However, , , and can each be edge-colored with colors.[2][16] Biggs[9] explains this problem with the following story: eleven soccer players in the fictional town of Croam wish to form up pairs of five-man teams (with an odd man out to serve as referee) in all 1386 possible ways, and they wish to schedule the games between each pair in such a way that the six games for each team are played on six different days of the week, with Sundays off for all teams. Is it possible to do so? In this story, each game represents an edge of , each weekday is represented by a color, and a 6-color edge coloring of provides a solution to the players' scheduling problem. HamiltonicityThe Petersen graph is a well known non-Hamiltonian graph, but all odd graphs for are known to have a Hamiltonian cycle.[17] As the odd graphs are vertex-transitive, they are thus one of the special cases with a known positive answer to Lovász' conjecture on Hamiltonian cycles in vertex-transitive graphs. Biggs[2] conjectured more generally that the edges of can be partitioned into edge-disjoint Hamiltonian cycles. When is odd, the leftover edges must then form a perfect matching. This stronger conjecture was verified for .[2][16] For , the odd number of vertices in prevents an 8-color edge coloring from existing, but does not rule out the possibility of a partition into four Hamiltonian cycles. References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||