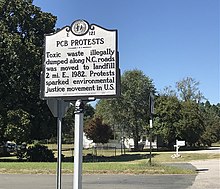

|

North Carolina PCB Protest, 1982 The North Carolina PCB Protest of 1982 was a nonviolent activist movement in Warren County, North Carolina, a predominantly black community where the state disposed of soil laced with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). The toxins leaked into the local water supply and sparked protests in which hundreds of people were arrested.[1] The protest is considered one of the origins of a global environmental justice movement.[2] Background The controversy dated back to 1978, when a transformer company in Raleigh began to dump industrial waste containing PCBs along rural roads in fifteen North Carolina counties rather than pay for proper disposal. Company owner Robert "Buck" Ward was sentenced to prison for these offenses in 1981.[3] Around this time, residents of Warren County began to notice contamination and met in small groups to organize protests.[4] By 1982, the state had selected the rural unincorporated Warren County community of Afton to store the PCB-contaminated soil and similar waste collected from Ward's illegal dumping sites.[4] Disposal of PCBs had been regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, but the Act did not allow public participation in the selection of dumping sites.[5] As construction of the landfill began, local residents protested and were soon joined by national organizations including the United Church of Christ and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Longtime civil rights activist Benjamin Chavis tied this protest to racial equality, helping to define the environmental justice movement.[6] At the time, African Americans were approximately 60% of the population of Warren County[7] with 25% of residents living in poverty.[6] ProtestWhen the North Carolina government refused to reconsider its decision to place the toxic dump in Warren County, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) coordinated protests in which more than 500 people were arrested, including Chavis and Congressman Walter Fauntroy.[2] Marches and non-violent street protests lasted for six weeks.[1] These were the first major actions in which protesters theorized that their communities had been targeted for toxic waste disposal due to their racial characteristics and lack of political power.[1] The protesters were inspired by some earlier actions involving social justice and the environment, such as the organization of immigrant farm workers by Cesar Chavez in the early 1960s and protests over waste facilities in African American neighborhoods in Houston and New York City later that decade.[1] The protests failed to stop the construction of the facility in Afton, though they have been widely cited for inspiring a new type of environmental justice movement in which the residents of poor and minority communities addressed the impacts of toxic waste and industrial activities in their communities.[2] The National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) called the protest "the first major milestone in the national movement for environmental justice."[1] North Carolina Governor Jim Hunt later promised the residents of Warren County that the landfill site would be decontaminated as soon as suitable technology became available.[8] This process began in 1993 and was completed in 2004.[9] References

Additional reading

External links |