|

Nicolaas Bidloo

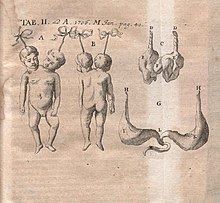

Nicolaas Bidloo (c. 1673/74 – 23 March 1735) was a Dutch physician who served as the personal physician of Tsar Peter I of Russia (Peter the Great). Bidloo was the director of the first hospital in Russia as well as the first medical school in Russia, and is considered one of the founders of Russian medicine.[1] BiographyEarly yearsBidloo was born in Amsterdam and came from a Mennonite family of scientific repute. His father Lambert Bidloo (1638–1724) was an apothecary and wrote a treatise on botany[2] and his uncle Govert Bidloo was the personal physician of King William III of England. In 1690 he confirmed his belief and became a member of the Mennonites in Amsterdam. Bidloo studied medicine at Leiden University, where his uncle Govert was a professor, and in January 1697 received a doctorate in the medical sciences. In 1701 the 27-year-old Nicolaas married Clasina Claes in Amsterdam.[3] Personal physician of Peter the GreatIn 1702, Bidloo signed a contract with the Russian ambassador to serve as Tsar Peter the Great's personal physician for a period of six years, at an annual salary of 2500 Dutch guilders (an extraordinarily high pay for a physician at that time). He arrived in Russia with his family in June 1703. As the tsar's personal physician, Bidloo accompanied Peter the Great on his travels, but found himself with very little to do, as the tsar was in excellent health.[3]  As part of this efforts to modernize Russia, Peter the Great in 1707 ordered the establishment of the country's first hospital and appointed Bidloo as its director. Peter the Great granted Bidloo a piece of land on the Yauza River, in the German Quarter on the outskirts of Moscow, to build the hospital as well as a house for himself and his family. As part of the hospital, Bidloo founded the first Russian medical school, where he gave instruction in anatomy[4] and surgery to 50 students. The hospital and medical school also contained Russia's first anatomical theater. Here, Peter the Great regularly attended dissections.[5] In 1710 Bidloo published the first Russian textbook on medical studies, a 1306-page manual of surgery entitled Instructio de chirurgia in theatro anatomico studiosis proposita a.d. 1710, januarii die 3.[1][3][6] The hospital burned down in 1721 but was restored and reopened in 1727.[7] Bidloo died in St Petersburg. He was succeeded by Antonius Theils, and in 1742 by Herman Kaau Boerhaave, nephew of Herman Boerhaave.[8] His brother Abraham Kaau Boerhaave arrived in 1746 and was appointed in the Kunstkamera.[9] Bidloo's gardensBidloo laid out extensive gardens on the hospital estate, including ponds, statues, a triumphal arch, and a botanical garden based on the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden. He also advised Peter the Great on horticulture, gardens and fountains. The tsar visited Bidloo's garden frequently, even when Bidloo was not at home. Supposedly, Bidloo was also one of the original designers of the Summer Garden and Peterhof in St. Petersburg. In 1730 Bidloo published a manuscript on his private garden, intended as a souvenir for his children. The manuscript included 19 drawings which Bidloo made of the gardens.[3][10][11] The manuscript is now in the collection of Leiden University.[12] References

|

||||||||||||