|

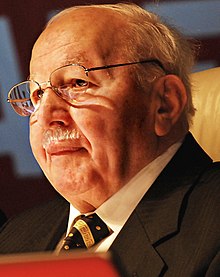

Necmettin Erbakan

Necmettin Erbakan (29 October 1926 – 27 February 2011) was a Turkish politician, engineer, and academic who was the Prime Minister of Turkey from 1996 to 1997. He was pressured by the military to step down as prime minister and was later banned from politics by the Constitutional Court of Turkey for allegedly violating the separation of religion and state as mandated by the constitution.[1][2] The political ideology and movement founded by Erbakan, Millî Görüş, argues that Turkey can develop with its own power by protecting its religious values and moving forward with faster steps by rivaling the Western countries in favor of closer relations to Muslim countries.[3] With the Millî Görüş ideology, Erbakan was the founder and leader of several prominent Islamic political parties in Turkey from the 1970s to the 2010s, namely the National Order Party (MNP), the National Salvation Party (MSP), the Welfare Party (RP), the Virtue Party (FP), and the Felicity Party (SP). Early life and educationErbakan was born in Sinop, at the coast of Black Sea in northern Turkey.[4] His father was Mehmet Sabri, a judge from the prominent Kozanoğlu family of Cilicia and his mother Kamer was a Circassian from a known family in Sinop[5][6] and the second wife of Mehmet Sabri.[7] After high school education in Istanbul High School, he graduated from the Mechanical Engineering Faculty at the Istanbul Technical University in 1948, and received a PhD degree in mechanical/engine engineering from the RWTH Aachen University.[4] After returning to Turkey, Erbakan became lecturer at the İTÜ and was appointed professor in 1965 at the same university.[4] After working some time in leading positions in the industry, he switched over to politics, and was elected deputy of Konya in 1969.[4] He was a member of the Community of İskenderpaşa, a Turkish sufistic community of the Naqshbandi tariqah.[8] Political activitiesOne of the leading names in Turkish politics for decades, Erbakan was the leader of a series of Islamic political parties that he founded or inspired. These parties rose to prominence only to be banned by Turkey's secular authorities. In the 1970s, Erbakan was chairman of the National Salvation Party which, at its peak, served in coalition government with the Republican People's Party of Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit during the Cyprus crisis of 1974. In the wake of the 1980 military coup, Erbakan and his party were banned from politics.[4] He reemerged following a referendum to lift the ban in 1987 and became the leader of the Welfare Party.[4] His party benefited in the 1990s from the acrimony between the leaders of Turkey's two most prominent conservative parties, Mesut Yılmaz and Tansu Çiller, leading his party to a surprise success in the general elections of 1995. Since the tensions between the military and the Islamists led to a civil war in Algeria, Erbakan said "Turkey will not turn into Algeria" in 1992[9] and 1997.[10] But on 10 May 1997 Welfare Party Şanlıurfa MP İbrahim Halil Çelik threatened that "If you try to close the İmam Hatip schools, blood will be spilled. It would be worse than Algeria."[11] Erbakan and his associates developed ties with the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in Algeria and when Erbakan visited the American Muslim Council in October 1994, he engaged with FIS representatives.[12] PremiershipAfter the short premiership of Mesut Yılmaz after the 1995 elections collapsed in 1996 due to a censure motion by the Welfare Party, Erbakan became the prime minister in coalition with Çiller's True Path Party (DYP). As prime minister, he attempted to further Turkey's relations with the Arab nations.[4] In addition to trying to follow an economic welfare program, which was supposedly intended to increase welfare among Turkish citizens, the government tried to implement a multi-dimensional political approach to relations with the neighboring countries. The coalition government received criticism for Erbakan's foreign policy. When Erbakan went on an African tour, visiting Egypt, Nigeria, and Libya, his passiveness toward the Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, angered even his own constituents back home. Erbakan appeared passive in the face of Gaddafi's reprimands that Turkey's Israel-friendly foreign policy was proof that the imperialists powers had placed it "under occupation" and that Turks had lost their "national will". Gaddafi also lambasted Turkey for its Kurdish policy during this joint press conference with Erbakan, greatly embarrassing the Turkish prime minister.[13] This public browbeating did not play well at home. Despite these reactions, Erbakan maintained his pro-Islamist foreign-policy focus, hewing to his National Outlook origins. He suggested an Islamic security organization to rival NATO, as well as an Islamic currency called the dinar. Deeply alarmed, the military established an initiative called the "Western Working Group", tasked with monitoring the party's activities.[14] Erbakan's image was damaged by his famous speech making fun of the nightly demonstrations against the Susurluk scandal. He was widely blamed at the time for his indifference. The Turkish military gradually increased the urgency[clarification needed] and frequency of its public warnings to Erbakan's government, eventually prompting Erbakan to step down in 1997. At the time there was a formal rotation deal between Erbakan and Tansu Çiller, the leaders of the coalition — Erbakan was to act as the prime minister for a certain period (a fixed amount of time, which was not publicized), then he would step down in favour of Çiller. However, Çiller's party was the third-largest in the parliament, and when Erbakan stepped down, President Süleyman Demirel asked Mesut Yılmaz, leader of the second-largest party, to form a new government instead.[15][16][17] Post-premiershipIn an unprecedented move, Erbakan's ruling Welfare Party was subsequently banned by the courts, which held that the party had an agenda to promote Islamic fundamentalism in the state, and Erbakan was barred once again from active politics.[18] He had argued that a truly democratic country should not shut down a political party for its beliefs. He was tried and sentenced to two years and four months imprisonment in the so-called Lost Trillion Case, which involved the use of forged documents to prevent the return of Treasury grants in the amount of around one trillion old Turkish lira, $3.3MM in today's currency[when?], following the ban of the party in 1997.[19][20] Despite often being under political ban, Erbakan nonetheless acted as a mentor and informal advisor to former Welfare Party members who founded the Virtue Party in 1997, among them being the future Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The Virtue Party was found unconstitutional in 2001 and forcibly banned; by that time, Erbakan's ban on political activities had ended, and he founded the Felicity Party, of which he was the leader in 2003–2004 and again from 2010[21] until his death. Death Erbakan died on 27 February 2011 at 11:40 local time of heart failure at Güven Hospital in Çankaya, Ankara.[22][23][24] His body was transferred to Istanbul, and following the religious funeral service at the Fatih Mosque, the attending crowd accompanied his coffin the about 4 km (2.5 mi) way to the Merkezefendi Cemetery, where he was laid to rest beside his wife Nermin. He did not wish a state funeral, however his funeral was attended by highest state and government officials.[25] ViewsErbakan's ideology is set forth in a manifesto, entitled Millî Görüş (National View), which he published in 1969.[4] The organisation of the same name, which he founded and of which he was the leader, upholds nowadays that the word "national" is to be understood in the sense of monotheistic ecumenism.[26][27] According to The Economist, at his death Erbakan was acknowledged as a moderating force on Turkey's Islamists, and made Turkey as a possible model for the Arab world as well.[28] His foreign policy had two main pillars: Pan-Islamism, and struggle against Zionism. He created "D-8" or The Developing Eight, to achieve an economic and political unity among Muslim countries. It has eight members, including Turkey, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Egypt, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nigeria. Although a rigorous Islamist and avid opposer of secularism, Erbakan developed a friendship with Jean-Marie Le Pen, due to their shared belief that European and Islamic civilization were incompatible and their similar right-wing ideologies.[29][30] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||