|

Nathaniel Ames

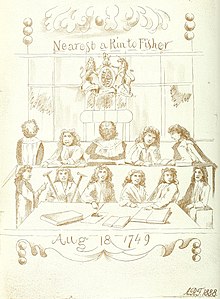

Nathaniel Ames[a] (July 22, 1708 – July 11, 1764) was a colonial American physician who published a popular series of annual almanacs. He was the son of Nathaniel Ames first (1677–1736) and the father of Nathaniel and Fisher Ames. The family was descended from William Ames of Bruton, Somerset, England, whose son William emigrated to Massachusetts and settled at Braintree as early as 1640. Early lifeCaptain Nathaniel Ames, father of this entry's subject, lived at Bridgewater and there married Susannah Howard on December 2, 1702.[1] Six children were born to them, of whom Nathaniel second was the eldest son.[2] [b] His father is said to have been learned in astronomy and mathematics, as well as practicing medicine. Nothing is known of his son's education, but he became a physician, probably without other medical training than instruction from his father, apprenticeship to some country doctor, and reading medical volumes. Ames' almanacIn 1725, Ames published the first annual number of his almanac, which was to remain a popular New England almanac for a half-century.[3][4] At this time, he was still living at home in Bridgewater, and although the almanac bears on the title-page "by Nathaniel Ames, Jr.," it may well be that the boy, then only seventeen years old, received some help from his mathematical parent.[5] He is said to have moved to Dedham in 1732[6] and his name is entered from that place on the list of subscribers to Prince's Chronology, to which most of the subscriptions were made in 1728.[7] Life in DedhamAmes moved to Dedham, Massachusetts in 1732 and developed a reputation as the village eccentric.[8] He frequently feuded with his next door neighbors, Rev. Samuel Dexter and then Rev. Jason Haven.[9] Ames v. Gay On September 14, 1735, Ames married Mary, daughter of Capt. Joshua Fisher of Dedham, by whom, on October 24, 1737, he had a son, Fisher Ames. Fisher died less than a year later, on September 17, 1738, surviving his mother, however, who had died on November 11, 1737.[10] Ames’ wife had owned a tavern, and the situation gave rise to Ames v. Gay, one of the famous lawsuits of New England. Ames (a compulsively litigious man) claimed inheritance to her estate according to the Province law through their son Fisher against his mother-in-law Hannah, who claimed the rights to it under the Common law, a struggle continued by her family after she died in December 1744. In August 1749 Ames won the case, and thus established an exception to the rule of inheritance in Massachusetts. However, two of the eleven Superior Court of Judicature justices were against him, leading the normally amiable Ames to an especially vituperative stance against lawyers for the rest of his career.[c] He took down his tavern sign and replaced it with a cartoon of the judges, all easily identifiable. Each was shown studying the Province laws, except the two dissenters, who had their backs turned to the law books. Chief Justice Paul Dudley, one of the dissenters, sent the sheriff to arrest Ames and confiscate the libelous portrait. Ames was warned and quickly substituted Matt. 16:4: “A wicked and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign; and there shall no sign be given unto it.”[11] Second wifeOn October 30, 1740, he married his second wife Deborah Fisher, daughter of Jeremiah Fisher, by whom he had six children, the eldest being Nathaniel, and the third son being Fisher Ames.[d] In that year, 1740, he was also one of the subscribers to the celebrated Land Bank.[12] In addition to his duties as local doctor, as publisher of the almanacs, and as amateur astronomer, Ames for many years ran the well-known "Sun" tavern, which brought him an economically and politically strategic position; as taverns often doubled as courthouses, Ames was also a common lawyer, a business that aroused the anger of trained legal practitioners. The contemporary entry in John Whiting's Diary reads "Jan. 25, 1750, Dr. Ames began to keep tavern”, although Briggs and Kittredge provide different dates for the commencement of this venture.[6][13] He continued to live at Dedham until his death of fever in 1764. After Ames died, his widow continued to keep the tavern until she married Richard Woodward, when it became the Woodward Tavern,[14] under which name it was known as the site where the Suffolk Resolves were drawn up in 1774.[10] It was demolished in 1817 and is now the site of the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds. Death and tombAmes died on July 11, 1764. When he died, his estate was valued at £1,561.4s.7d in real estate and £409.9s.6.25d in personal effects.[15] In 1775, during the Siege of Boston, Jabez Fitch, a young officer in the Colonial Army, visited Ames' tomb in the Old Village Cemetery in Dedham.[16] Finding the tomb open, he entered, opened the casket, and examined the decomposing body.[16] Faith Huntington was buried in his tomb on November 28, 1775, after which mourners went back to the Ames Tavern.[17] LegacyHis chief importance is as founder and editor of his almanacs, the publishing of which his son, Nathaniel third (a Harvard graduate and physician), continued for ten years after his father's death. The father issued the first number in 1725, three years before James Franklin started his in Rhode Island and eight years before Benjamin Franklin inaugurated Poor Richard's Almanack. Ames must have been a household word throughout New England, for it is said that the circulation of his almanac, with its sharp-tongued commentary on Massachusetts politics, religion, and social life ran to 60,000 copies.[18] Moses Coit Tyler considered it as superior to Franklin's, which it resembled in many ways. Besides the astronomical observations, Ames published short articles, extracts from the English poets, such as Milton and Pope, and used the same pithy and witty maxims as made the reputation of Franklin, such as: "All men are created equal, but differ greatly in the sequel." He had taste for good literature and considerable wit, though some of it seems a trifle forced today, and the quality rather improved when the almanac was continued by his somewhat abler son, who nevertheless was not the genial gentleman his father was, genuinely liking only farmers and despising printers.[19] Ames, however, undoubtedly did much to bring, if only in brief allusions and extracts, some knowledge of the better English authors to innumerable New England farmhouses.[5] Ames gave rise to an entire industry, and he had many imitators. Among those who followed in his footsteps was Dudley Leavitt of Meredith, New Hampshire, a teacher, newspaper publisher and polymath who published his first Leavitt's Farmers Almanack in 1797. See alsoNotes

References

Works cited

External links

|

||||||||||||||