|

Nathan the Wise

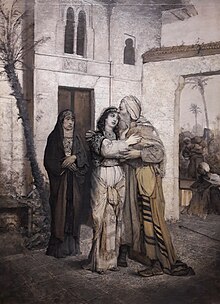

Nathan the Wise (original German title: Nathan der Weise, pronounced [ˈnaːtaːn deːɐ̯ ˈvaɪzə] ) is a play by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing from 1779.[1] It is a fervent plea for religious tolerance.[2] It was never performed during Lessing's lifetime and was first performed in 1783 at the Döbbelinsches Theater in Berlin.[2] Set in Jerusalem during the Third Crusade, it describes how the wise Jewish merchant Nathan, the enlightened sultan Saladin, and the (initially anonymous) Templar, bridge their gaps between Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. Its major themes are friendship, tolerance, relativism of God, a rejection of miracles and a need for communication. SynopsisThe events take place during the Third Crusade (1189–1192) during an armistice in Jerusalem. When Nathan, a wealthy Jew, returns home from business travel, he learns that his foster daughter Recha was saved from a house fire by a young Christian Templar. The knight, in turn, owes his life to the Muslim ruler of Jerusalem, Sultan Saladin, who pardoned him as the only one of twenty prisoners because he looks like Saladin's late brother Assad. Despite these fortunate circumstances, the rational-thinking Nathan is unwilling to believe the events to be a miracle and also convinces Recha that believing in the work of guardian angels is harmful. Saladin, somewhat indifferent in terms of money, is currently in financial trouble. That is why, on the advice of his more calculating sister Sittah, he has the wealthy Nathan brought to him to test his generosity, which is praised throughout Jerusalem: Instead of asking him directly for a loan, Saladin pretends that he wants to test Nathan's famous wisdom and asks him about the "true religion". Nathan, who had already been informed about Saladin's financial troubles by his friend Al-Hafi and warned of his financial recklessness, recognizes the trap. He decides to answer Saladin's question with a "fairy tale", the so-called "ring parable". Deeply impressed, Saladin immediately understands this parable as a message about the equality of the three major monotheistic religions. Moved by Nathan's humanity, he asks him to be his friend from now on. Nathan willingly agrees and, on top of that, grants Saladin a generous loan without being asked. The Templar, who had saved Recha from the flames, but, until now, was not willing to meet her, is united with her by Nathan. He falls head over heels in love with her and wants to marry her on the spot. However, his name makes Nathan hesitate to give his consent, which insults the Templar. When he finds out from Recha's companion Daja, a Christian, that Recha is not Nathan's biological daughter, but is only adopted, and that her biological parents were Christians, he turns to the patriarch of Jerusalem for advice. Although the Templar frames his request as a hypothetical case, the fanatical head of the church guesses what this is about and wants to search for "this Jew" immediately and have him burned at the stake for temptation to apostasy. He does not consider Nathan's noble motives and the fact that Nathan did not raise the Christian child as a Jew, but on the contrary in no belief, does not soften the patriarch's stance, but aggravates him: "That’s nothing! Still the Jew is to be burnt— / And for this very reason would deserve / To be thrice burnt." Records of the friar who once brought Recha to Nathan as a toddler finally reveal that the Christian Templar and Recha are not only brother and sister – hence Nathan's reservations about marriage – but also the children of Saladin's brother Assad. These connections are revealed to everyone in the final scene at Saladin's palace, which ends with all main characters repeatedly embracing each other in silence. Ring ParableThe centerpiece of the work is the "Ring Parable", narrated by Nathan when asked by Saladin which religion is true: an heirloom ring with the magical ability to render its owner pleasing in the eyes of God and mankind had been passed down from father to son. For generations, each father had bequeathed the ring to the son he loved most. When it came to a father with three sons whom he loved equally, he promised it (in "pious weakness") to each of them. Looking for a way to keep his promise, he had two replicas made, which were indistinguishable from the original, and gave on his deathbed a ring to each of them.[3] The brothers quarreled over who owned the real ring. A wise judge admonished them that it was impossible to tell at that time – that it even could not be discounted that all three rings were replicas, the original one having been lost at some point in the past; that to find out whether one of them had the real ring it was up to them to live in such a way that their ring's powers could be proven true, to live a life that is pleasant in the eyes of God and mankind rather than expecting the ring's miraculous powers to do so. Nathan compares this to religion, saying that each of us lives by the religion we have learned from those we respect.[4] An older rendition of the Ring Parable and its surrounding narrative involving Saladin and a wealthy Jew can be found in the 73° story of Il Novellino,[5] in the third tale of the first day in Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, and in the story Ansalon Giudeo from Bosone da Gubbio's novel Fortunatus Siculus: ossia L'avventuroso Ciciliano.[6] Even earlier versions can be found in the Tractatus de diversis materiis praedicabilibus by Étienne de Bourbon,[7] in Li dis dou vrai aniel[8] and in the Gesta Romanorum.[9][10][11][12] BackgroundThe character of Nathan is to a large part modeled after Lessing’s lifelong friend, the eminent philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Like Nathan the Wise and Saladin, whom Lessing brings together over the chessboard, they shared a love for the game of chess.[13] The motif of the Ring Parable is derived from a complex of medieval tales. The first version of the story to appear in German was the tale of Saladin's table in the Weltchronik by Jans der Enikel. Lessing probably first read an older version of the “Ring Parable” in Boccaccio's Decameron.[14] English language translations and stage adaptations

RevivalsIn 1922 it was adapted into a silent film of the same title. In 1933, the Kulturbund Deutscher Juden (Culture Association of German Jews) was created in Germany, enabling Jewish artists who had recently lost their jobs to perform to exclusively Jewish audiences. On October 1, Nathan the Wise became the first performance of this new federation. It was the only time the play was performed in Nazi Germany.[20] In the early 21st century, the Ring Parable of Nathan the Wise was taken up again in Peter Sloterdijk's God's Zeal: The Battle of the Three Monotheisms.[21] Edward Kemp's 2003 version of the play, first produced by the Minerva Theatre, Chichester,[16] was used in 2016 in New York by the Classic Stage Company with F. Murray Abraham in the lead.[1] The play was produced at the Stratford Festival (May 25–October 11, 2019) with Diane Flacks as Nathan.[22] Notes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Nathan der Weise.

|

||||||||||||||||