|

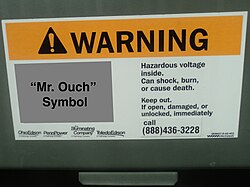

Mr. Ouch Mr. Ouch is a hazard symbol developed by the US’s National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) to represent electrical hazard within pad-mounted transformers. Unlike other high-voltage warning symbols, Mr. Ouch was specifically designed with young children in mind.[1] It is part of NEMA Standard 260-1996, Safety Labels for Pad-Mounted Switchgear and Transformers Sited in Public Areas, which lays out design guidelines for a complete label design that incorporates the Mr. Ouch symbol.[1] Mr. Ouch is similar in name, purpose, and concept to the UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh's "Mr. Yuk" design[2] used to label poisonous substances, although the two symbols were developed independently. AppearanceMr. Ouch is anthropomorphized electricity. The design shows a snarling, octopus-like creature with jagged, lightning-bolt arms throwing a child backwards.[3][4] Background In early 1981, several member companies of NEMA began studying how to prevent young children from being electrocuted by electrical transformers. This followed incidents where transformer cabinets were vandalized or left unlocked, allowing access to the high-voltage equipment inside and resulting in disfigurement and death. NEMA realized that existing signage did not adequately convey the danger, either because it required literacy (text-only warnings) or because existing symbols were too abstract to register on a child (typically bolts of electricity).[4] Concerned about "failure to warn" lawsuits, NEMA began exploring ways of warning young children about the dangers of exposed high-voltage equipment.[5][4] Member companies within NEMA's Transformer Section formed a task force—the Task Force on Safety Labels for Pad-Mounted Switchgear and Transformers Sited in Public Areas—to design a safety label that very young children would understand, as well as standards on how that label was to be used.[4][1] Design processAt the beginning of the project, the task force reached out to transformer manufacturers in an effort to build consensus for standardizing a design. Two goals were decided on: a symbol that would warn young children away from electrical equipment, and a label that would make the hazards within the equipment clear to adults, and encourage them to contact utility companies when unsecured equipment was discovered. NEMA hired the Agnew Moyer Smith company of Pittsburgh, PA to design the label, and the George R. Frerichs & Associates Testing Organization of Chicago to test children's reactions to it. Testing of the first iterations of symbol designs in fall of 1981, initially choosing sixteen different illustrations to test on children.[6] The test groups were located in Chicago, IL and San Antonio, Texas, and consisted of an equal number of English and non-English-speaking children, aged 2.5 to 6 years old, both boys and girls. Of the sixteen symbols, they were placed into groups of four, and children were asked questions while being shown the symbols.[6] In phase 1 testing, the following questions were posed:[6]

From that group of sixteen illustrations, NEMA selected the four most successful designs for further testing and review:[6]

In Phase 2 testing, the revised versions of these symbols would respectively become Pictograms Q, R, S, and T. Phase 2 testing, the four symbols recommended from Phase 1 testing, were revised, based on responses given during testing. Among changes from Phase 1 testing were: Pictogram N had a plug added to the end of the wire, Pictogram R removed the cartoon elements and had the lightning bolt stab the palm of the hand, Pictogram S[b] would see a total redesign, that retained the core concept of an angry ball of energy with lightning bolts shooting out, while adding a drawing of a child being electrocuted, Pictogram T eliminated the two symbol design in favor of a single symbol showing a child being shocked by an open cabinet.[6] These revised symbols would be placed through testing in Chicago, in early 1982. The children were similar to the groups of Phase 1 testing, identical in age range and language. Phase 2 testing was similar to, but more detailed, adding additional questions, and using photographs as part of the question asking process.[6] Phase 2 questions were:[6]

Of the four symbols, the one children most strongly associated with danger was Pictogram S, Mr. Ouch.[6] While it was not the most successful at conveying to children the hazard was electrical, it was the most successful at conveying the presence of a hazard and encouraging avoidance. Pictogram Q, with the wire with a plug shocking the hand, was more successful at conveying that the hazard was specifically posed by electricity, it failed to inspire the same recognition of danger from children, and in some cases children were encouraged by the symbol to engage in a hazardous behavior. For these reasons, Pictogram S, then referred to as "Mr. Lightning", was selected by the NEMA as the symbol for inclusion on their new label system.

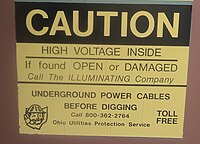

NEMA standard 260 was the first warning label system developed and standardized by an industry.[5] It went beyond just the Mr. Ouch symbol, incorporating the new symbol as part of complete label design that would include a new header design with the 'international alert symbol', an exclamation mark inside a triangle, on a single solid color background. The accompanying text message went beyond just stating the hazard posed, high voltage electricity; and included a clear statement of the consequences, how to avoid them, and what to do if the equipment wasn't secured. These additions helped impress the gravity of the danger, and alerted the public that an unsecured box was dangerous, should be reported promptly, and who to report it to.[4] The standard included two designs, one intended for use on the outside of equipment, and a more urgent label for placing inside equipment, where danger of electric shock was always present.[1][4] The continued effectiveness of the symbol was shown in a 1995 study, presented at the annual meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, which confirmed that Mr. Ouch most effectively suggested an electrical hazard, out of four other symbols.[7] Usage The intended usage of 'Mr. Ouch' labels, are ground level electrical equipment, often pad-mounted transformers, that are accessible by members of the public, such as those situated in residential neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and near schools.[1] The Mr. Ouch symbol is copyrighted by the NEMA, to protect the symbol by limiting its use to safety signage and educational purposes. Usage guidance for the signage is specified in NEMA Standards Publication 260-1996, Safety Labels for Pad-Mounted Switchgear and Transformers Sited in Public Areas.[1] The label for use on the external housing of equipment uses the "Warning" signal word, for situations that could result in serious injury or death, and referred to "Hazardous voltage inside" and "Can shock, burn...".[1][4] The other design, intended for the inside of equipment, visible when equipment is opened or unsecured, uses the "Danger" signal word, for situations that will result in serious injury or death and "Will shock, burn..."[1][4] When first introduced in 1983, the Mr. Ouch label design was not considered a replacement for OSHA warning signage, and had to accompany signage compliant with OSHA's existing ANSI Z35.1968-based standards in order to satisfy OSHA safety regulations.[8][9] However, the Mr. Ouch label designs shown in the 1996 revision of NEMA-260 share many characteristics of OSHA's current ANSI-Z535-based safety standards[10] —clear pictogram, international alert symbol, and direct explanatory language—and NEMA-260-1996 does not specify that Mr. Ouch labels must be used in accordance with other signage. Since the mid-2010s, the label has been able to appear alone, without older ANSI Z35-1968 labels. Wisconsin Energies created an educational video for schools, to help children recognize Mr. Ouch.[11] An educational comic book, Mr. Ouch and Electrical Safety, intended to educate children to stay away from equipment marked with the Mr. Ouch label, was also designed.[12] See alsoNote

References

|